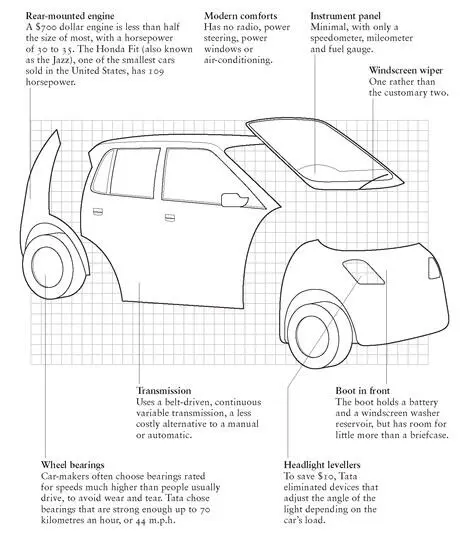

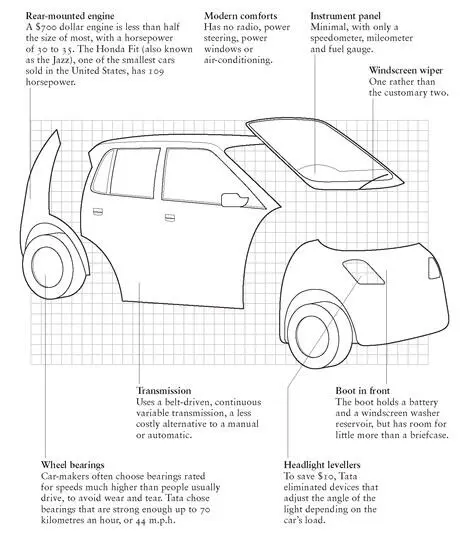

Figure 19. How to make a cheap car, Indian-style: the Tata Nano.

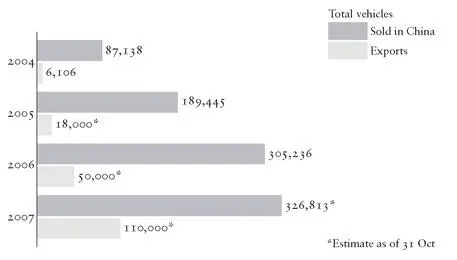

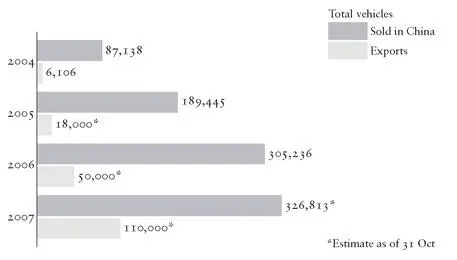

Figure 20. Sales of Chery cars, 2004-7.

This suggests that we should expect Chinese firms to enter at the bottom end of the global market for mass consumer goods, initially mainly in the developing world — of which there is already clear evidence [538] [538] Geely, for example, has announced that it will assemble cars in Indonesia; ‘Geely to Make Cars in Indonesia as Malaysia Refuses to Host Plant’, South China Morning Post , 28 September 2006. ‘Chery Gears Up for US Roll-out’, South China Morning Post , 26 April 2006.

— but later moving into the developed world. It will take time for firms like Chery and Geely to establish themselves in Western markets, where standards and tastes are very different from the ‘cheap-end’ advantage presently enjoyed by Chinese firms. Indeed, both have postponed their American launch dates until around 2009 or later. A cautionary tale in this respect is provided by TCL, the Chinese TV manufacturer, which entered into a joint European venture with the French firm Thomson. It made a number of serious miscalculations based on its ignorance of the European market and announced in 2006 that it would close its European operations. [539] [539] ‘TCL to Close TV Factories in Europe’, South China Morning Post , 1 November 2006.

But TCL is an exception: Chinese electrical appliance firms have overwhelmingly chosen to establish their overseas manufacturing subsidiaries in developing rather than developed countries. There is a certain parallel, in this context, between Chinese firms initially targeting the developing world and the earlier experience of Japan and Korea. Japanese companies, for example, first dominated the then relatively poor local East Asian markets and only later began to make serious inroads into Western markets. In Europe and the United States, furthermore, both Japan and South Korea started at the cheap end of the market then steadily worked their way up. The same will be broadly true of China, except it will probably prioritize the developing world even more strongly. Chinese exports to Africa, the Middle East, Asia and South America have recently been growing far more rapidly than those to the United States. China sent more than 31 per cent of its exports to the US in 2000 but that figure had dropped to just over 22 per cent by early 2007 and is now 18 per cent. [540] [540] ‘ US Market is Losing Its Appeal to China ’, International Herald Tribune , 18 April 2007.

Although China is already making significant progress in low- and medium-technology industries such as white goods and motor vehicles, it is also intent, in the longer term, on becoming a major player in a high-tech industry like aerospace. China will shortly begin production of its own regional passenger jet, [541] [541] ‘ China ’s Plane Ambitions Take Off’, posted on www.bbc.co.uk/news.

while Airbus has announced its intention of shifting some of its manufacturing capacity to China. [542] [542] ‘Airbus Near a Deal for Assembly Line in China ’, International Herald Tribune , 16 March 2006.

Possibly as a way of leapfrogging the development process, the main Chinese aerospace group was reported in 2007 to be considering investing in, or bidding for, six of Airbus’s European plants that had been deemed surplus to requirements, although in the event no offer materialized. [543] [543] ‘Chinese Group to Bid for All Six Airbus Plants’, Guardian , 19 June 2007.

Given time, it is inconceivable that China — already the second largest aircraft market in the world [544] [544] ‘Air Battle on the Ground in China ’, International Herald Tribune , 28 February 2007.

— will not become a major aircraft producer in its own right. The fact that it is steadily developing its space programme — it conducted a successful manned space flight in 2003, launched a lunar orbiter in 2007 and plans to launch its own space station in 2020 — indicates that China is intent on acquiring highly sophisticated technical competence in the aerospace field. [545] [545] ‘China Plans Space Station in 2020’ and ‘China Launches First Moon Orbiter’, posted on www.bbc.co.uk/news.

Looking into the future, therefore, one can anticipate a number of broad trends regarding the development of Chinese companies. We will continue to see the slow but steady emergence of Chinese multinationals in areas which play to their domestic comparative advantage, such as white and electrical appliances, motorcycles, trucks and cars. [546] [546] For the steady penetration of Chinese TV sets into the US market, see Shenkar, The Chinese Century , pp. 152-3; and China Goes Global (London: Financial Times , 2005).

We can expect Chinese brands to emerge in fields such as sports equipment (for example Li-Ning) [547] [547] ‘Faced with a Steep Learning Curve’, Financial Times special report on global brands, 23 April 2007; ‘China Aims for Spot among Top World Brands’, South China Morning Post , 5 October 2006.

— linked to China ’s growing strength as a sporting nation — and Chinese medicine. We are likely to see Chinese firms become major competitors in high-tech areas such as aerospace (AVIC 1), telecommunications (China Mobile and Huawei), computers (Lenovo) [548] [548] Lenovo is the world’s fourth biggest PC seller; Sonia Kolesnikov-Jessop, ‘Putting Lenovo’s Brand on the Global Map’, International Herald Tribune , 27-8 September 2008.

and perhaps in renewable energy (for example, Suntech Power Holdings). China ’s banks, construction companies and oil companies are already rapidly emerging as global giants, helped by the scale of the Chinese market and the resources at their disposal. In 2007 the boom on the Shanghai Stock Exchange saw PetroChina briefly overtake Exxon as the world’s largest company. By the end of 2007 China possessed three of the world’s five largest companies, by value though not by sales, namely PetroChina, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) and China Mobile. [549] [549] ‘PetroChina Overtakes Exxon After Shanghai Debut’, Financial Times , 5 November 2007; Gideon Rachman, ‘China Has Risen’, international affairs blog, Financial Times , 9 November 2007; also Andy Xie, ‘China’s Bubble May Burst But the Impact Will Be Limited’, Financial Times , 16 October 2007.

We can also anticipate some of the big Chinese firms seeking to expand overseas by taking over foreign firms. There have already been examples of this with Lenovo acquiring IBM Computers and the Chinese oil giant CNPC unsuccessfully seeking to buy the US oil firm Unilocal; awash with cash and eager to shortcut their expansion, it is not difficult to imagine this happening on a much wider scale. An obvious area is commodities, with Chinalco’s stake in Rio Tinto, the Anglo-Australian mining group, an example. [550] [550] ‘A Complex Rationale for China ’s Raid on Rio ’, Financial Times , 13 February 2008.

With many Western companies suffering from a serious shortage of cash as a result of the credit crunch, the takeover opportunities for cash-rich Chinese companies, the oil companies in particular, are likely to be considerable, with Western political opposition weakened by the recession. [551] [551] Lex, ‘Chinese Oil Majors’, Financial Times , 29 October 2008.

Meanwhile the establishment of the China Investment Corporation, armed with funds of $200 billion, of which some $80 billion is for external investment, could give China growing potential leverage over those foreign companies in which it decides to invest. [552] [552] ‘ China Turns Risk Averse, Even as Capital Outflows Rise’, Financial Times , 17 January 2008.

Finally, we should not forget the increasing importance of Chinese subcontractors as ‘systems integrator’ firms in the global supply chain of many foreign multinationals, a development which might, in the long term at least, prove to have a wider strategic significance for these multinationals in terms of their management, research capability and even ownership. [553] [553] Nolan, Transforming China , pp. 222, 227-8.

Читать дальше