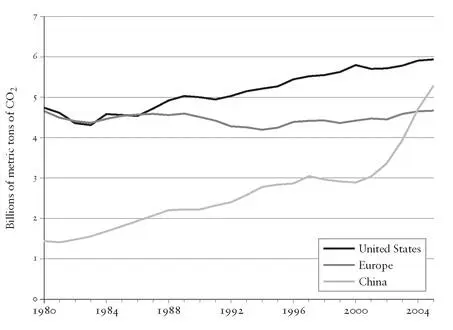

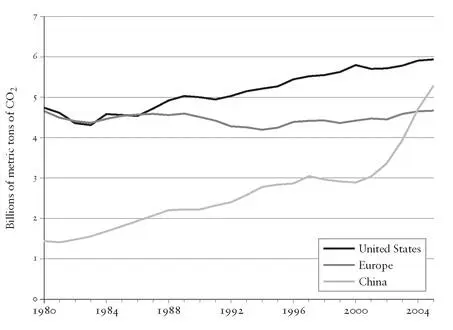

Figure 15. CO2 emissions compared.

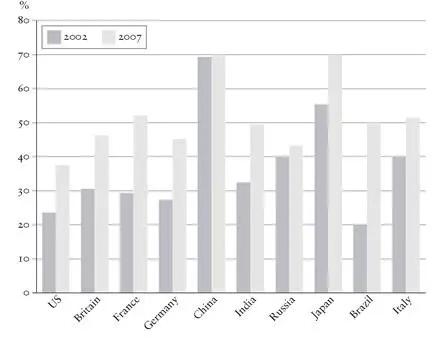

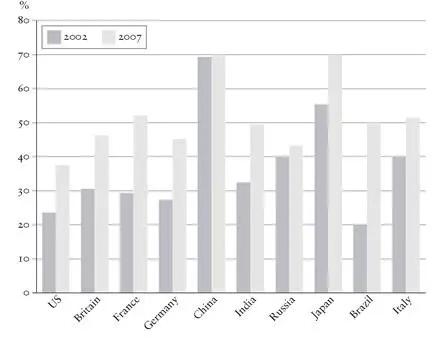

Figure 16. Growing concern over environmental problems.

China ’s position on climate change is evolving rapidly. The two targets it has adopted as part of its 2007 energy security strategy will have a significant impact on reducing the growth in emissions — namely, decreasing the energy intensity of the Chinese economy by 20 per cent by 2010 and increasing the use of renewables from 5 per cent to 20 per cent of energy production by 2020. It is already the world’s largest user of alternative energies, including wind power. [504] [504] Dominic Ziegler, ‘Reaching for Renaissance: A Special Report on China and Its Region’, The Economist , 31 March 2007.

It is making huge investments in a wide range of clean-technology innovations, especially in wind, solar and hydrogen. Such is the scale of these investments that whatever technologies China develops in clean and renewable energies are likely in practice to become the new global standard. It could easily become the world’s leading manufacturer of renewable energy plants, and at a price, furthermore, affordable to other developing countries. [505] [505] John Warburton and Leo Horn, ‘China’s Crisis: A Development Perspective (Part Two), 25 October 2007, posted on www.chinadialogue.net; Keith Bradsher and David Barboza, ‘Pollution from Chinese Coal Casts a Global Shadow’, New York Times , 11 June 2006.

It is widely believed that in the relatively near future some of the most exciting potential breakthroughs in photovoltaics (the use of solar cells for the generation of electricity) and hydrogen-powered vehicles may come out of China rather than the United States. [506] [506] Porritt, ‘ China Could Lead the Fight for a Cooler Climate’.

The two largest Chinese car producers are in the process of launching hybrid models, and, encouraged by the government, they, together with other manufacturers, have ambitious plans to become world leaders in electric and other alternative-energy vehicles. [507] [507] ‘ China Carmakers Go Green in Drive for Profit’, Financial Times , 20 April 2008.

Just as its economic development combines both the backward and the advanced, so the same could well prove to be the case with the environment, as the drastic action taken by the central government in advance of the Beijing Olympics to try and improve the capital’s appalling air quality, including major restrictions on the use of cars, illustrated. [508] [508] Each car had to spend one day a week off the road. These restrictions were reintroduced again after the Olympics in an effort to improve air quality.

At present, China’s comparative advantage lies in low-end manufacturing, where it is able to exploit the huge supply of cheap unskilled labour and thereby produce at rock-bottom prices — or ‘China prices’, as the new global benchmark has become known — for the world market. [509] [509] Chunli Lee, ‘Strategic Alliances of Chinese, Japanese and US firms in the Chinese Manufacturing Industry: The Impact of “China Prices” and Integrated Localization’, paper presented for the Fairbank Center for East Asia Research, Harvard University, October 2004.

In the longer run, there are two inherent problems with this. First, in terms of the total costs of getting a product to market, the proportion represented by manufacturing is very small — around 15 per cent of the final price — with the bulk of costs being creamed off by design, marketing, branding and so forth, tasks which are still overwhelmingly carried out in the developed world. [510] [510] James Kynge, China Shakes the World: The Rise of a Hungry Nation (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2006), pp. 160-62.

Second, most of China ’s exports are produced by Western and Japanese multinationals, with Chinese manufacturers cast predominantly in the role of subcontractors. In other words, China ’s role is basically as the low-end manufacturing subcontractor in the multifarious global operations of multinationals based in the developed countries. [511] [511] Gilboy, ‘The Myth behind China ’s Miracle’, pp. 4–5.

There is, however, plenty of evidence that China is steadily climbing the technological ladder. Like all newcomers, it has been obliged to make it up as it goes along and find its own distinctive path. One avenue used by China to gain access to new technologies has been a combination of copying, buying, and cajoling foreign partners in joint-ventures to transfer technology in return for being granted wider access to China ’s market. The lure of the latter has proved a powerful bargaining counter, especially with second-tier multinationals. [512] [512] Kynge, China Shakes the World , pp. 108-10, 112; Shenkar, The Chinese Century , pp. 66-8.

In a short space of time, China has already overtaken many South-East Asian countries in important areas of technology, and its ability to drive a hard bargain with foreign multinationals has been a major factor in this. While Proton, Malaysia ’s national car company, has been unable to persuade any of its various foreign partners — most notably Mitsubishi — to transfer key technology, the Chinese car companies have, one way or another, been rather more successful. The bargaining counter of size carries great clout: China has fifty times the population of Malaysia. [513] [513] Kynge, China Shakes the World , p. 109.

There is another route by which China has been negotiating its way up the technological ladder: when foreign multinationals move their manufacturing operations to China, there is a strong tendency for other functions to follow so as to take advantage of economies of scale, for reasons of convenience, and because highly skilled Chinese labour is plentiful and cheap. [514] [514] Prestowitz, Three Billion New Capitalists , pp. 147, 149; Kynge, China Shakes the World , pp. 83-4; Shenkar, The Chinese Century , p. 165.

The textile industry in Italy, for instance, has progressively migrated to China, starting with manufacturing, followed by more value-added processes like design. [515] [515] Kynge, China Shakes the World , pp. 72, 78–82.

Microsoft, Motorola and Nokia have all established major research and development centres in Beijing, while Lucent-Alcatel has done the same in Nanjing. As a consequence, Chinese professionals will become increasingly important players in the R & D activity of such leading-edge multinationals. [516] [516] Prestowitz, Three Billion New Capitalists , p. 143.

In the longer term, however, the key to China ’s technological potential will lie in its ability to develop its own high-level research and development capacity. Because China ’s growth has hitherto relied overwhelmingly on imported technologies, only 0.03 per cent of Chinese firms own the intellectual property rights of their core technologies. Moreover, Chinese companies spend on average only 0.56 per cent of turnover on research and development, and even in large firms this only rises to 0.71 per cent. [517] [517] James Wilsdon and James Keeley, China: The Next Science Superpower? (London: Demos, 2007), p. 9.

However, enormous efforts are being made to change this state of affairs, with the aim of increasing R & D spending from $24.6 billion (1.23 per cent of GDP) in 2004, to $45 billion (2 per cent of GDP) in 2010, and $113 billion (2.5 per cent of GDP) in 2020. [518] [518] Ibid., p. 7.

Considerable progress has already been made in a very short space of time. China has become a major player in the production of scientific papers, its contribution rising from around 2 per cent of world share in 1995 to 6.5 per cent in 2004. [519] [519] Ibid., p. 16.

Citation rates, although very low, are also rising exponentially. [520] [520] Ping Zhou and Loet Leydesdorff, ‘The Emergence of China as a Leading Nation in Science’, Research Policy , 35 (2006), pp. 86–92, 100; Wilsdon and Keeley, China , pp. 16–17.

The overall figures hide strengths in particular areas, most notably material science, analytical chemistry and rice genomics. A recent analysis of nanoscience publications shows that China ranked second behind only the US in 2004. [521] [521] Zhou and Leydesdorff, ‘The Emergence of China as a Leading Nation in Science’, p. 100.

Not surprisingly, publications are concentrated amongst a handful of elite centres such as the Chinese Academy of Science, Beijing University and Tsinghua University (also in Beijing), which China is seeking to develop as world-class institutions. [522] [522] Wilsdon and Keeley, China , p. 32.

Читать дальше