China is in the midst of what Marx described — writing of the British Industrial Revolution — as primitive accumulation, or what we now know as economic take-off: the process in which the majority of the working population moves from the land to industry, from the countryside to the cities. Between 1952 and 2003, agriculture’s share of GDP fell from 60 per cent to 16 per cent and its share of employment from 83 per cent to 51 per cent. [445] [445] Maddison, Chinese Economic Performance in the Long Run , p. 69.

Although it took China only 10 years to double its per capita output (1977- 87) — a measure of the speed of economic take-off — compared with 58 years for the UK, 47 for the US and 11 for South Korea, after three decades of economic growth averaging 9.5 per cent, [446] [446] Yu Yongding, ‘ China ’s Structural Adjustment’, p. 1

around half the people still work on the land. It is estimated that even 20 years hence around 20 per cent of the population will still live in the countryside. [447] [447] Interview with Yu Yongding, Singapore, 3 March 2006.

A crucial consequence of this relatively ‘limitless’ supply of rural labour is that wages for unskilled work will remain depressed for several decades to come: in other words, for much longer than was the case with the earlier Asian tigers. [448] [448] Andy Xie, Asia/Pacific Economics , report for Morgan Stanley, November 2002.

This does not mean that wages in the more developed regions like Guangdong will remain low: on the contrary, as we have seen, they have already risen considerably. [449] [449] ‘ Guangdong Factories Drop Cheap for Chic’, South China Morning Post , 17 March 2008; ‘End of an Era for Pearl River Delta’, South China Morning Post , 9 February 2008.

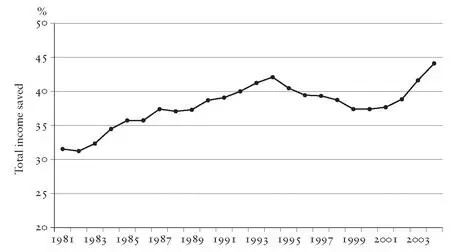

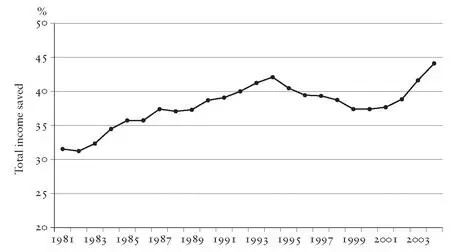

But in the poor, still largely rural, interior provinces they will continue to be much lower, which is the reason why low-end manufacturing is steadily relocating there. The rapid growth of the Chinese economy since 1978 has largely been a function of the extremely high rate of investment, in the region of 40 per cent of GDP for many years, presently edging closer to 45 per cent, and soon to approach 50 per cent. [450] [450] Yu Yongding, ‘China’s Rise, Twin Surplus and the Change of China’s Development Strategy’, unpublished paper, Namura Tokyo Club Conference, Kyoto, 21 November 2005, p. 12.

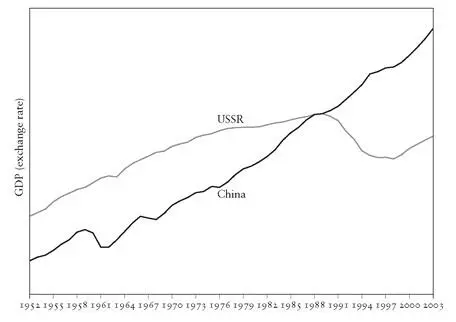

Such an extremely high rate of investment has been possible because of the similarly high rate of domestic savings, running at around 40 per cent of GDP, which, together with inward investment, has provided the main funds for China ’s take-off. In 2001 the average Chinese household saved 25.3 per cent of its disposable income, compared with 6.4 per cent in the US in 2002. The huge savings made by Chinese families have played a key role in funding the country’s rise (see Figure 11). [451] [451] Ibid., p. 11.

Figure 11. China’s savings rate from 1981.

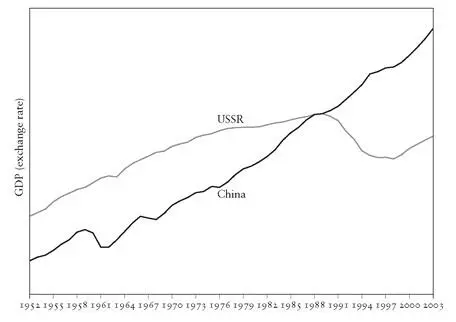

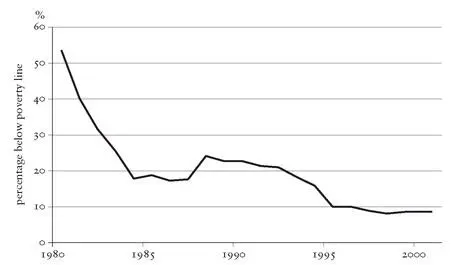

It is instructive to compare the experiences of China and Russia because both were confronted with the problem of how to move from a command to a market economy. Russia relied on the preferred Western prescription of shock therapy, which in the nineties led to hyper-inflation, large-scale capital flight, currency collapse and default on foreign debt. In contrast China, by pursuing a more gradualist approach, avoided hyper-inflation, the government remained internationally creditworthy and there was no capital flight. While in Russia the state sector was sold off at knock-down prices to assorted cronies, the state sector in China, rather than being subject to wholesale privatization, was contracted by a slow process of attrition. In Forbes Magazine ’s listing of the world’s 100 richest billionaires in 2007, thirteen were in Russia and none in China. In 1990, China’s GDP was less than twice as big as Russia’s; by 2003 it was more than six times as large. The subsequent rebound in the Russian economy, prior to the global downturn, was largely a result of the increase in the price of its oil and gas exports. The Chinese leadership has displayed great patience and considerable competence at tackling a succession of difficult and elusive problems. At the end of the nineties, for example, the government was faced with three extremely difficult domestic issues: closing a very large number of loss-making state enterprises; overhauling the state banks, which were saddled with a large and rising proportion of non-performing loans, mainly to indebted state enterprises; and strengthening the weak fiscal position of central government. A decade later, the government is well on the way to overcoming these problems, having greatly reduced the problem of indebted state enterprises, transformed the condition of the banking system and improved its own finances. [452] [452] Maddison, Chinese Economic Performance in the Long Run, pp. 94-6.

Figure 12. Economic performance of China and the USSR compared.

Given its scale and speed, China ’s economic transformation is surely the most extraordinary in human history, notwithstanding the sheer novelty of Britain ’s as the first. The government’s economic strategy, shrewd and far-sighted, has been very successful, [453] [453] Interview with Yu Yongding, Beijing, 6 December 2005: Wang Gungwu, ‘Ration alizing China ’s Place in Asia ’, in Reid and Zheng, Negotiating Asymmetry , p. 5.

resulting in stellar economic growth and a rise in per capita income from $339 in 1990 to over $1,000 in 2003, with the not unrealistic aim that this will be doubled within ten years. [454] [454] Yu Yongding, ‘ China ’s Rise, Twin Surplus and the Change of China’s Development Strategy’, p. 2.

Economic growth is no longer confined to a few ‘islands’ but has spread out in waves to most provinces of China, albeit in sharply varying degrees. In a remarkably short space of time, China has become the centre of global manufacturing. ‘Made in China ’ has become synonymous with a host of mass-produced consumer products throughout the world. It produces two-thirds of the world’s photocopiers, shoes, toys and microwave ovens; half its DVD players, digital cameras and textiles; one-third of its DVD-ROM drives and desktop computers; and a quarter of its mobiles, television sets, PDAs and car stereos. [455] [455] Prestowitz, Three Billion New Capitalists , p. 74.

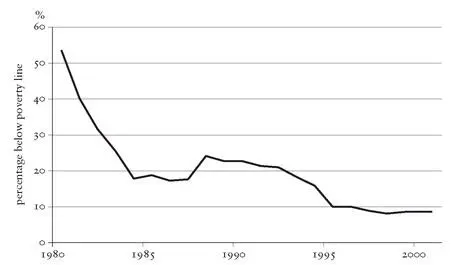

The country has borne witness to the greatest poverty-reduction programme ever seen, with the number of people living in poverty falling from 250 million at the start of the reform process in 1978 to 80 million by the end of 1993 and 29.27 million in 2001, thereby accounting for three-quarters of global poverty reduction during this period. [456] [456] Joseph Stiglitz, ‘Development in Defiance of the Washington Consensus’, Guardian , 13 April 2006.

Figure 13. The decline in poverty in China.

Although foreign multinationals dominate the country’s exports, home-grown Chinese firms like Haier, Konka, TCL, Huawei and Galanz have done well in such sectors as domestic appliances, television and telecommunications. Encouraged by the ‘Go Global’ campaign initiated by the government, the larger Chinese firms have begun to invest abroad and establish overseas subsidiaries. [457] [457] Oded Shenkar, The Chinese Century: The Rising Chinese Economy and Its Impact on the Global Economy, the Balance of Power and Your Job (New Jersey: Wharton School Publishing, 2006), p. 114.

China has made astounding economic progress, but its transformation is far from complete. It remains a work in progress. Although it is already the world’s second largest economy in terms of GDP (measured by purchasing power parity), this is primarily a consequence of population size rather than economic sophistication. Can China fulfil its enormous potential and become an economic superpower?

Читать дальше