The approach of the Chinese leadership, following Deng’s emergence as the paramount leader, had been built on caution and pragmatism, notwithstanding the obvious radicalism of the reform process. They eschewed shock treatment and grand gestures. Although drawing on elements of neo-liberalism, they resisted the Washington orthodoxy and instead pursued a very home-grown approach. [433] [433] Danni Rodrik, One Economics Many Recipes: Globalization, Institutions, and Economic Growth (Princeton: Princeton University, 2007), pp. 238-9.

They were painstakingly meticulous in the way that they sought to introduce reforms by a gradual process of constant testing and trial and error. The state, in the time-honoured Chinese fashion, remained at the heart of this process of reform, even though the latter was to involve a drastic contraction in its economic role, with the share of government revenue decreasing from around one-third of GDP in 1978 to 17 per cent in 2005. [434] [434] Angus Maddison, Chinese Economic Performance in the Long Run, Second Edition, Revised and Updated: 960 - 2030 AD (Paris: OECD, 2007), pp. 64, 89.

For the Chinese leadership, the objective of economic reform was never Westernization, but rather a desire to restore the Party’s legitimacy after Mao through economic growth, [435] [435] Wang Gungwu, ‘Rationalizing China’s Place in Asia, 1800–2005: Beyond the Literati Consensus’, in Reid and Zheng, Negotiating Asymmetry , p. 5.

and thereby to build a strong nation and state. [436] [436] Gittings, The Changing Face of China , p. 186.

Political stability was accorded the highest priority. ‘[China ’s] modernization,’ Deng stated, ‘needs two prerequisites. One is international peace, and the other is domestic political stability.’ [437] [437] Zheng Yongnian, Will China Become Democratic ? p. 33.

The disintegration of the Soviet Union after 1989 only served to reinforce Deng’s belief in the vital importance of economic reform, an area in which the Soviet Union had palpably failed, and the need to avoid destabilizing political reforms, a trap which they saw Gorbachev as having fallen into. [438] [438] Ibid., pp. 238-9.

The Asian financial crisis in 1997- 8 similarly confirmed the Chinese leadership in its aversion to shock treatment: that China should move with great caution in its financial reform and resist any premature liberalization of the capital account that would allow the free movement of capital into and out of China, and consequent floating of the Chinese currency, the renminbi (also called the yuan), which might lead to speculative attacks on the currency and the consequent destabilization of the economy, as happened to South Korea, Thailand and Indonesia — to their great cost — during the Asian crisis. [439] [439] Yu Yongding, ‘Opinions on Structure Reform and Exchange Rate Regimes Against the Backdrop of the Asian Financial Crisis’, unpublished paper, Japanese Ministry of Finance, 2000, pp. 1-11; Wang Yizhou, ‘Political Stability and International Relations in the Process of Economic Globalisation — Another Perspective on Asia’s Financial Crisis’, unpublished article, Beijing, 2000, pp. 1-13; and Wang Zhengyi, ‘Conceptualising Economic Security and Governance: China Confronts Globalisation’, Pacific Review , 17:4 (2000), p. 542.

(As a consequence, the renminbi remains, unlike the dollar, yen and euro, for example, a non-tradeable currency.)

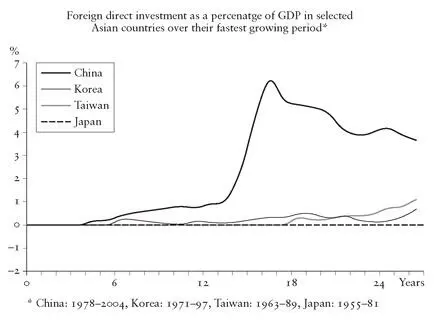

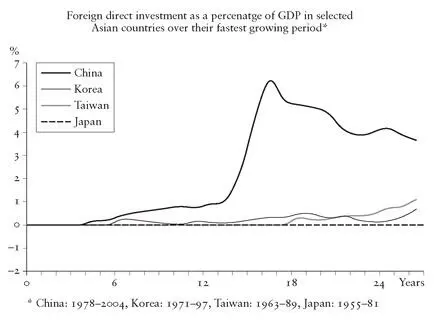

In response to the challenge posed by an increasingly globalized economy, the Chinese leadership, mindful of the need to accelerate the process of reform, did, however, opt for one important element of shock treatment. During the nineties, by dismantling tariff barriers and allowing huge flows of foreign direct investment — in contrast to the economic strategy pursued by Japan, South Korea and Taiwan — they created a brutal competitive environment in which domestic companies desperately sought to survive against far richer and more advanced Western and Japanese rivals. This rapid opening up enabled the Chinese economy to take advantage of enormous flows of foreign capital and had the merit of forcing Chinese companies to learn from the outside world, [440] [440] Yu Yongding, ‘ China ’s Structural Adjustment’, unpublished paper, Seoul Conference, 2005, p. 2.

but the cost was high, with many struggling to survive. While their North-East Asian neighbours enjoyed a prolonged period of protection from external competition, during which their companies were given time to develop, China, in comparison, had none. Chinese companies were obliged to sink or swim, and the conditions attached to China ’s subsequent membership of the WTO meant the state faced various restrictions on the extent to which it was permitted to help state-owned enterprises, although it found various ways of circumnavigating some of them. [441] [441] Nolan, Transforming China , p. 61; Lex, ‘ China and International Law’, Financial Times , 30 April 2008.

Figure 10. The role of foreign direct investment in China compared with other Asian tigers.

Although the earlier phase of reform concentrated on stimulating the growth of the rural economy, by the end of the eighties the centre of gravity had decisively shifted to the cities and the industrial economy. Already, during the eighties, the Guangdong economy became a microcosm of the future shape and comparative advantage of the fast-changing Chinese economy, with Hong Kong entrepreneurs moving their manufacturing operations out of the city-state to neighbouring Guangdong province in order to take advantage of far cheaper labour; as a result, Guangdong rapidly became Hong Kong ’s manufacturing base. This process quickly spread north and east-wards during the course of the nineties, its magnitude transformed by the flood of Western and Japanese direct investment at the end of that decade in anticipation of China ’s membership of the WTO in 2001. Just as China pursued an open policy on trade, it adopted a similar approach towards inward investment. Since 1978 China has received $500 billion in foreign direct investment, ten times the total accumulated by Japan between 1945 and 2000. In 2003 China became the world’s largest recipient of foreign direct investment, overtaking the United States. [442] [442] Clyde Prestowitz, Three Billion New Capitalists: The Great Shift of Wealth and Power to the East (New York: Basic Books, 2006), p. 61.

The inward investment was mainly ploughed into the local subsidiaries of foreign multinationals with the purpose, following the example of Hong Kong, of exploiting the huge resources of cheap labour in order to make exports as globally competitive as possible. Foreign firms are now responsible for up to 60 per cent of all Chinese exports, and dominate high-tech exports with a share of around 85 per cent. [443] [443] George J. Gilboy, ‘The Myth behind China ’s Miracle’, Foreign Affairs , July/ August 2004, pp. 4–5.

China, in the process, has become the ‘workshop of the world’, by far the cheapest national base for low- and medium-end manufacturing on the planet.

As a result of the systematic lowering of tariffs, one of the singular features of the Chinese economy is its huge exposure to foreign trade, which accounts for around 75 per cent of GDP, far in excess of other major economies like the United States, India, Japan and Brazil, where the figure is 30 per cent or less. [444] [444] ‘The Dragon and the Eagle Survey’, The Economist , 2 October 2004, p. 11.

Such exposure makes China that much more significant in the global economy; it also leaves the country more vulnerable to external shocks such as a global downturn, a US recession or growing protectionist sentiment in the West.

Читать дальше