Between 1500 and 1800, stagnation gave way to vigorous economic growth and reasonable prosperity. There was a steady increase in the food supply, due to an increase in land under cultivation — the result of migration and settlement in the western and central provinces, greater productivity (including the use of new crops like corn and peanuts) and better irrigation. [217] [217] Fairbank and Goldman, China , pp. 168-9.

These developments sustained a fivefold increase in China ’s population between 1400 and 1800, whereas between 1300 and 1400 it had fallen sharply. [218] [218] Angus Maddison, The World Economy: Historical Statistics (Paris: OECD, 2003), p. 249.

China ’s performance during this period has tended to be overshadowed by the dynamism of the earlier medieval economic revolution; unlike during the Song dynasty, this later growth was achieved with relatively little new invention. In the eighteenth century China remained the world’s largest economy, followed by India, with Europe as a secondary player. Adam Smith, who saw China as an exemplar of market-based development, observed in 1776 that ‘ China is a much richer country than any part of Europe.’ [219] [219] Quoted by Andre Gunder Frank, ReOrient: Global Economy in the Asian Age (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), p. 279. See Giovanni Arrighi, Adam Smith in Beijing: Lineages of the Twenty-First Century (London: Verso, 2007), pp. 25-6, 58-9, 69.

It was not until 1850, indeed, that London was to displace Beijing as the world’s largest city. [220] [220] R. Bin Wong, China Transformed: Historical Change and the Limits of European Experience (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2000), p. 27. ‘Until about 1800,’ argues Andre Gunder Frank, ‘the world economy was by no stretch of the imagination European-centred nor in any significant way defined by or marked by any European-born “capitalism” — it was preponderantly Asian-based.’ Frank, ReOrient , pp. 276-7.

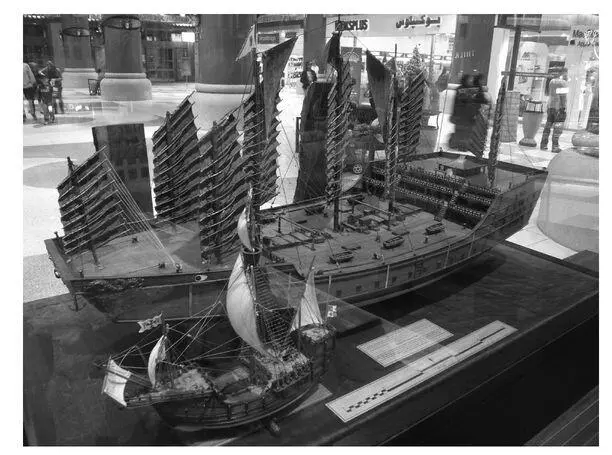

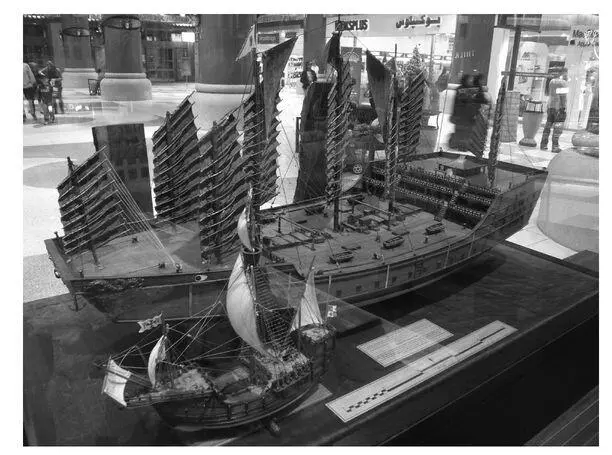

A model of one of Zheng He’s ships, shown in comparison to one of Christopher Columbus’s

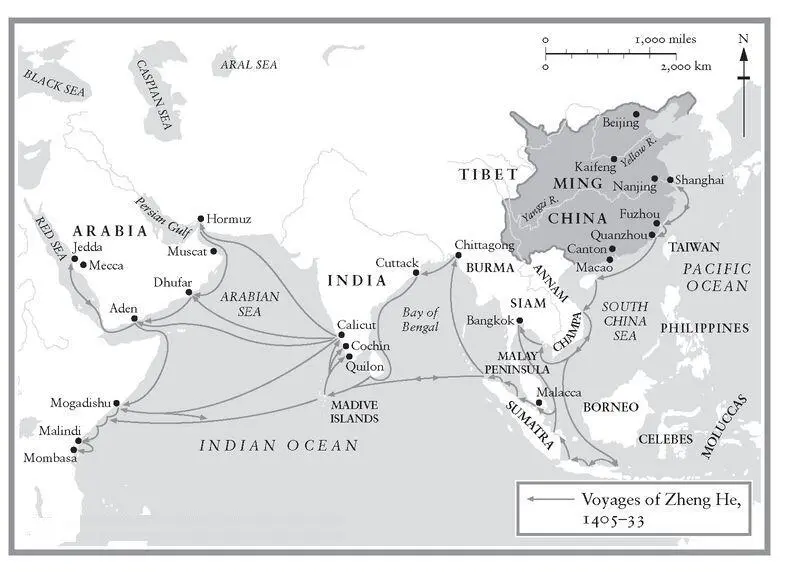

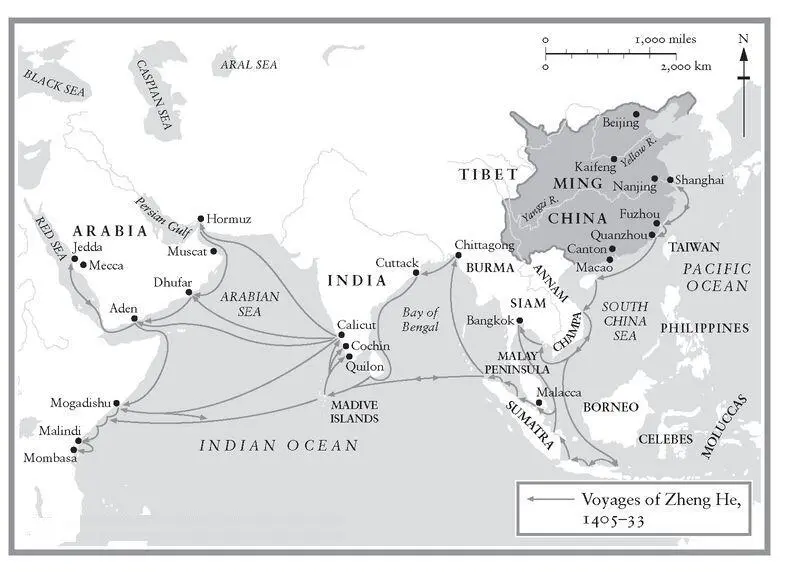

Map 7. Zheng He’s Expeditions

As we saw in Chapter 2, Britain was able to escape the growing resource constraints at the end of the eighteenth century by deploying the resources of its colonies, together with an abundant supply of accessible domestic coal. But what exactly happened to China, which enjoyed neither? There was almost certainly enough capital available, especially given the relatively small amounts involved in the take-off of the cotton industry in Britain. Although Chinese merchants did not enjoy the same kind of independent and privileged status that they did in Britain, always being subordinate to the bureaucracy and the landowning gentry, they were widely respected and enjoyed growing wealth and considerable power. [221] [221] Fairbank and Goldman, China , p. 180.

There may have been rather less protection for investment in comparison with Europe, but nonetheless there were plenty of very large Chinese enterprises. China ’s markets were no less sophisticated than those of Europe and were much longer established. Mark Elvin argues that the reason for China ’s failure was what he describes as a ‘high-level equilibrium trap’. [222] [222] Elvin, The Pattern of the Chinese Past , pp. 298–316; also, pp. 286-98.

China ’s shortage of resources in its densely populated heartlands became increasingly acute: there was a growing lack of wood, fuel, clothing fibres, draught animals and metals, and there was an increasing shortage of good farmland. Hectic deforestation continued throughout the nineteenth century and in some places the scarcity of wood was so serious that families burned little but dung, roots and the husks of corn. In provinces such as Henan and Shandong, where population levels were at their most dense, forest cover fell to between 2 per cent and 6 per cent of the total land area, which was between one-twelfth and one-quarter of the levels in European countries like France at the time. [223] [223] James Kynge, China Shakes the World: The Rise of a Hungry Nation (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2006), pp. 131-2.

The pressure on land and other resources was driven by the continuing growth of population in a situation of relative technological stasis. Lacking a richly endowed overseas empire, China had no exogenous means by which it could bypass the growing constraints.

With the price of labour falling, profit margins declining and static markets, there was no incentive to invest in labour-saving machinery; instead there was a premium on conserving resources and fixed capital. In such a situation there was little reason to engage in the kind of technological leap into the factory system that marked Britain ’s Industrial Revolution. In other words, it was rational for the Chinese not to invest in labour-saving machinery. As Elvin argues:

In the context of a civilization with a strong sense of economic rationality, with an appreciation of invention such that shrines were erected to historic inventors… and with notable mechanical gifts, it is probably a sufficient explanation of the retardation of technological advance. [224] [224] Elvin, The Pattern of the Chinese Past , pp. 314-15.

With growing markets and a rising cost of labour, on the other hand, investment in labour-saving machinery was entirely rational in the British context and was to unleash a virtuous circle of invention, application, increased labour productivity and economic growth; in contrast, China remained trapped within its old parameters. In Britain the domestic system, based on small-scale family units of production, proved to be the precursor of the factory system. In China, where such rural industrialization was at least as developed as it was in Britain, it did not. While Britain suggested a causal link between the domestic and the factory systems, this was not true in China: widespread rural industrialization did not lead to a Chinese industrial revolution. [225] [225] Ibid., pp. 281-2; Bin Wong, China Transformed , pp. 34, 41-4, 49; Mark Elvin, ‘The Historian as Haruspex’, New Left Review , 52, July-August 2008, p. 96.

The most striking difference between Europe and China was not in the timing of their respective industrializations, which in broad historical terms was similar, separated by a mere two centuries, but rather the disparity between the sizes of their polities, which has persisted for at least two millennia and whose effects have been enormous. It is this, above all, which explains why Europe is such a poor template for understanding China. After the collapse of the Roman Empire, Europe was never again to be ruled, notwithstanding the ambitions of Napoleon and Hitler, by an imperial regime with the capacity to exercise centralized control over more or less the entire continent. Political authority, instead, was devolved to many small units. Even with the creation of the modern nation-state system, and the unification of Germany and Italy, Europe remained characterized by its division into a multi-state system. In contrast, China retained the imperial state system that emerged after the intense interstate competition — the Warring States period — that ended in the third century BC, though this was to assume over time a range of different forms, including, as in the case of the Mongol Yuan and the Manchu Qing dynasties, various phases of foreign rule. [226] [226] Gernet, A History of Chinese Civilization , p. 53.

Apart from Outer Mongolia, China’s borders today remain roughly coterminous with those the country acquired during the period of its greatest geographical reach under the Qing dynasty (1644–1912). China ’s equilibrium state has been that of a unified agrarian empire in contrast to Europe, which for two millennia has been an agglomeration of states. [227] [227] Bin Wong, China Transformed , p. 76.

Читать дальше