Nor was the country endowed by its history with the ability or facility to change direction. Ever since 1868, through every historical twist and turn, it had displayed an extraordinary ability to retain its focus and maintain a tenacious commitment to its long-term objective. Japan might be described as single-path dependent, its institutions able to display a remarkable capacity to keep to their self-assigned path. This has generated a powerful degree of internal cohesion and enabled the country to be very effective at achieving long-term goals. By the same token, however, it also made changing paths, of which Japan has little experience, very difficult. The only major example was 1868 itself and that was in response to a huge external threat. [171] [171] Interview with Peter Tasker, Tokyo, June 1999.

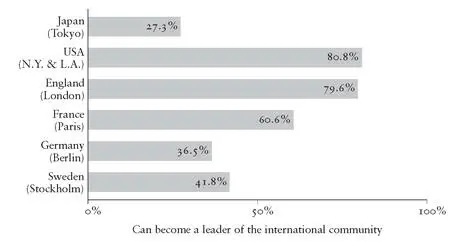

Figure 7. Japanese pessimism about their international role and influence.

The post-bubble crisis, which was followed by a long period of stagnation, led to much heart-searching and a deep sense of gloom. Some even went so far as to suggest that Japan had suffered two defeats: one in 1945 and another in the 1990s. [172] [172] Interview with Shunya Yoshimi, Tokyo, 1999.

The pessimism that engulfed the country revealed the underlying fragility of the contemporary Japanese psyche. Having finally achieved their goal, they were filled with doubt as to what to do next. As the United States regained its dynamism and Japan was becalmed, there was a widespread sense that its achievement was little more than a chimera, that it was always destined to live in the shadow of the West. [173] [173] Interview with Valerie Koehn, Tokyo, June 1999; interview with Shunya Yoshimi, Tokyo, June 1999; Sawa, Japan Times , 30 May 2005.

Japan’s psychological fragility in the face of the post-bubble crisis is a stark reminder of how difficult the process of catch-up — in all its many aspects — is for non-Western countries. Here was a country whose historical achievement was remarkable by any standards; which had equalled or pulled ahead of the West by most measures and comfortably outstripped the great majority of European countries that it had originally sought to emulate; which had built world-class institutions, most obviously its major corporations, and become the second wealthiest country in the world — and yet, in its moment of glory, was consumed by self-doubt.

In this context, it is important to understand the nature of Japan’s self-perception. Unlike the European or American desire to be, and to imagine themselves as, universal, the Japanese have had a particularistic view of their country’s role, long defining themselves to be on the periphery of those major civilizations which, in their eyes, have established the universal norm. As we have seen, China and the West constituted the two significant others from which Japan has borrowed and adapted, and against which the Japanese have persistently affirmed their identity. ‘For the Japanese,’ argues Kosaku Yoshino, ‘learning from China and the West has been experienced as acquiring the “universal” civilization. The Japanese have thus had to stress their difference in order to differentiate themselves from the universal Chinese and Westerners.’ [174] [174] Yoshino, Cultural Nationalism in Contemporary Japan , p. 11.

This characteristic not only distinguishes Japan from the West, which has been the universalizing civilization of the last two centuries, but also from the Chinese, who have seen their own civilization, as we shall explore later, in universalistic terms for the best part of two millennia.

Japan ’s post-1868 orientation towards the West was only one aspect of its new coordinates. The other was its attitude towards its own continent. Japan combined its embrace of the West with a rejection of Asia. The turn to the West saw the rise of many new popular writers, the most famous of whom was Fukuzawa Yukichi, who argued, in an essay entitled ‘On Leaving Asia’, published in 1885:

We do not have time to wait for the enlightenment of our neighbours so that we can work together towards the development of Asia. It is better for us to leave the ranks of Asian nations and cast our lot with civilized nations of the West. As for the way of dealing with China and Korea, no special treatment is necessary just because they happen to be our neighbours. We simply follow the manner of the Westerners in knowing how to treat them. Any person who cherishes a bad friend cannot escape his notoriety. We simply erase from our mind our bad friends in Asia. [175] [175] Quoted in Alastair Bonnett, The Idea of the West: Culture, Politics and History (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), p. 69.

The Japanese did not wait long to put this new attitude into practice. In 1894-5 they defeated China, gaining control of Taiwan and effectively also Korea. In 1910 they annexed Korea. In 1931 they annexed north-west China, from 1936 occupied central parts of China, and between 1941 and 1945 took much of South-East Asia. Between 1868 and 1945, a period of seventy-seven years, Japan engaged in ten major wars, lasting thirty years in total, the great majority at the expense of its Asian neighbours. [176] [176] Morishima, Why Has Japan ‘Succeeded’ , p. 96.

In contrast, Japan had not engaged in a single foreign war throughout the entire 250-year Tokugawa era. [177] [177] Van Wolferen, The Enigma of Japanese Power , p. 258.

Meiji Japan was thus intent not only on economic modernization and the emulation of the West, but also on territorial expansion, as the national slogan ‘rich country, strong army’ ( fukoku kyôhei ), which was adopted at the beginning of the Meiji period, implied. [178] [178] Morishima, Why Has Japan ‘Succeeded’ , p. 131.

Although Japan presented its proposal for the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere during the 1930s as a way of promoting Asian interests at the expense of the West, in reality it was an attempt to subjugate Asia in the interests of an imperial Japan. [179] [179] Christopher Bayly and Tim Harper, Forgotten Armies: The Fall of British Asia, 1941 - 1945 (London: Allen Lane, 2004), p. 3.

Map 4. Japan’s Colonies in East Asia

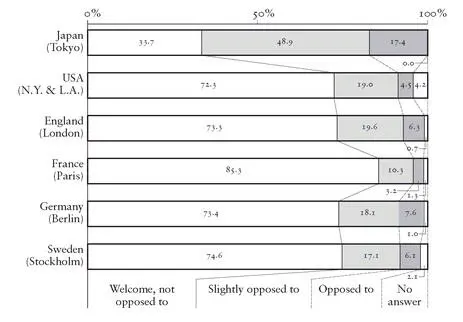

Figure 8. Japanese responses to the question, ‘How do you feel about you or a member of your family marrying a foreigner?’

Japan, unsurprisingly, saw the world in essentially similar terms to the deeply hierarchical nature of its own society. [180] [180] Van Wolferen, The Enigma of Japanese Power , p. 331; Benedict, The Chrysanthemum and the Sword , p. 96.

While looking up to the West, it looked down on Asia as backward and inferior, seeking to subjugate its own continent for the purpose of its enrichment and aggrandizement. Where once it had seen Chinese civilization as its superior, it now regarded the Chinese as an inferior race. [181] [181] Wilkinson, Japan Versus the West , p. 67.

The idea of a racial hierarchy has been intrinsic to the Japanese view of the world. Even today it continues to persist, as its relations with its East Asian neighbours demonstrate. Whites are still held in the highest esteem while fellow Asians are regarded as of lesser stock. [182] [182] Interview with Masahiko Nishi, University of Ritsumeikan, Kyoto, November 2005.

Racialized ways of thinking are intrinsic to mainstream Japanese culture, [183] [183] Racist adverts and books are not uncommon; for example, ‘Mandom Pulls the Plug on Racist TV Commercial’, Japan Times , 15 June 2005, and ‘“Sambo” Resurrectionists: What’s Racist?’, 16 June 2005 (concerning publication of Little Black Sambo ).

in particular the insistence on the ‘homogeneity of the Japanese people’ (even though there are significant ethnic minorities), the idea of a ‘Japanese race’ (even though the Japanese were the product of diverse migratory movements), and the widely held belief that the Japanese ‘blood type’ is associated with specific patterns of cultural behaviour. [184] [184] Van Wolferen, The Enigma of Japanese Power , pp. 265, 267; Frank Dikötter, ed., The Construction of Racial Identities in China and Japan (London: Hurst, 1997), p. 6.

Racial, ethnic and national categories overlap in Japanese conceptions of both themselves and, by implication, others also. [185] [185] Yoshino, Cultural Nationalism in Contemporary Japan , pp. 22-9.

This is illustrated by former prime minister Nakasone’s infamous remark in 1986 that the mental level in the United States was lower than in Japan because of the presence of racial minorities — specifically, ‘blacks, Puerto Ricans, and Mexicans’. [186] [186] Wilkinson, Japan Versus the West , p. 77.

Even today there is no law against racial discrimination. [187] [187] ‘Forum Mulls Ways to Make Racial Discrimination Illegal Here’, Japan Times , 2 July 2005; ‘UN Investigator Tells Japan to Draft Law Against Racism’, Japan Times , 13 July 2005.

Читать дальше