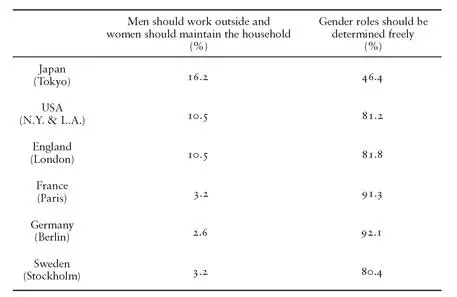

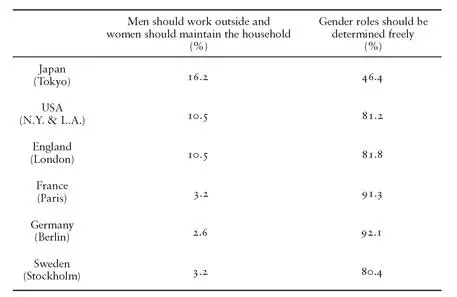

Table 1. Japanese attitudes towards gender.

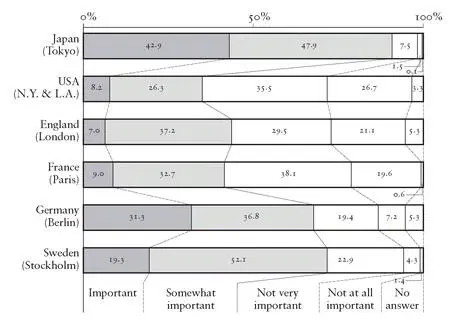

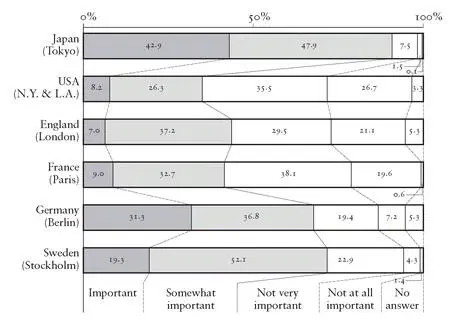

Figure 4. The Japanese commitment to work.

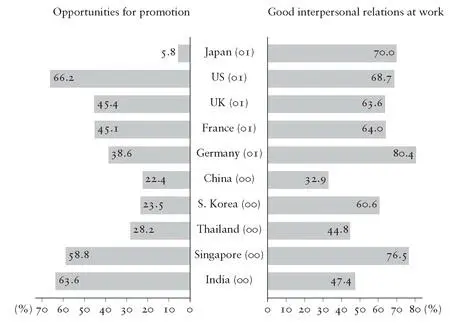

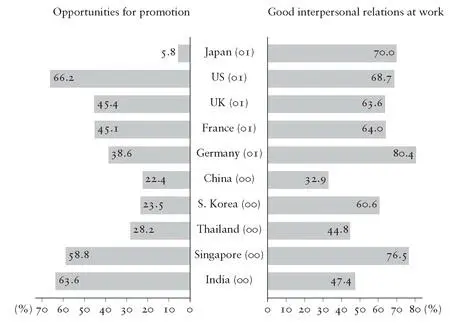

Figure 5. Japanese expectations of the workplace.

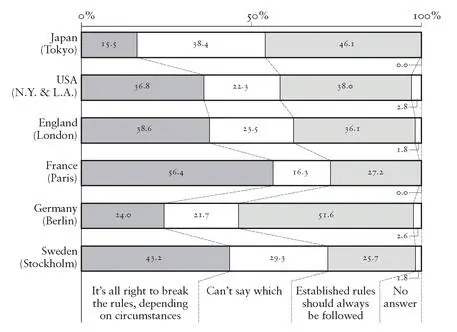

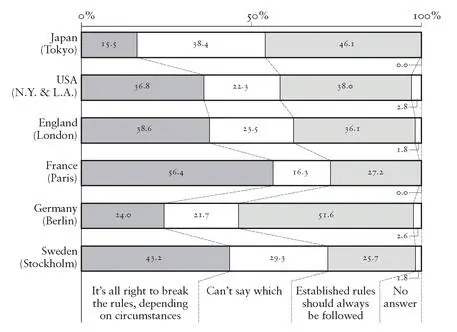

Figure 6. Japanese attitudes towards rules.

This picture of Japanese distinctiveness should not come as any great surprise. Even a relatively casual acquaintance with Japanese society conveys this impression. [160] [160] See Alan Macfarlane, Japan Through the Looking Glass (London: Profile Books, 2007), for an interesting discussion of Japan ’s distinctive modernity.

As the accompanying tables and charts illustrate, Japanese attitudes and values remain strikingly different from those of Western societies, notwithstanding the fact that they share roughly the same level of development. [161] [161] Lal, Unintended Consequences , p. 150.

The first reason for this hardly needs restating: cultural differences have an extraordinary endurance, with Japan’s rooted in a very different kind of civilization. [162] [162] Benedict, The Chrysanthemum and the Sword , p. 70; Yoshino, Cultural Nationalism in Contemporary Japan , pp. 68–95.

The second is historical: because the Meiji Restoration was a relatively recent event, Japan is still strongly marked by the proximity of its feudal past. [163] [163] Yoshino, Cultural Nationalism in Contemporary Japan , p. 199.

Furthermore, the post-1868 ruling elite consciously and deliberately set out to retain as much of the past as possible. The fact that the samurai formed the core of the new ruling group, moreover, meant that they carried some of the long-established values of their class into Meiji Japan and onwards through subsequent history. Post war Japan — like post-Restoration Japan — has been governed by an administrative class who are the direct descendants of the samurai : they, rather than entrepreneurs, run the large companies; they dominate the ruling Liberal Democratic Party; former administrators tend to be preponderant in the cabinet; and, by definition, of course, they constitute the bureaucracy, a central institution in Japanese governance. [164] [164] Van Wolferen, The Enigma of Japanese Power , Chapter 5; Chalmers Johnson, Japan: Who Governs? The Rise of the Developmental State (New York: W. W. Norton, 1995), Chapter 6, especially pp. 124-40; Lal, Unintended Consequences , p. 146; interview with Tadashi Yamamoto, Tokyo, June 1999.

Even the nature of governance still strongly bears the imprint of the past. Throughout most of Japan ’s recorded history, power has been divided between two or more centres, and that remains true today. The emperor is now of ceremonial and symbolic significance. The diet — the Japanese parliament — enjoys little real authority. The prime minister is far weaker than any other prime minister of a major developed nation, normally enjoying only a relatively brief tenure in office before being replaced by another member of the ruling Liberal Democrats. Cabinet meetings are largely ceremonial, lasting less than a quarter of an hour. Although formally Japan has a multi-party system, the Liberal Democrats have been in office almost continuously since the mid fifties and the factions within this party are in practice of much greater importance than the other parties. Power is therefore dispersed across a range of different institutions, with the bureaucracy, in traditional Confucian style, being the single most important. [165] [165] Van Wolferen, The Enigma of Japanese Power , Chapter 2. The conception of leadership is also very different from the Western model, less about strong leaders and much more concerned with consensus-building; Pye, Asian Power and Politics , p. 171.

Since the end of the American occupation, Japan has been regarded by the West as a democracy, but in reality it works very differently from any Western democracy: indeed, its modus operandi is so different that it is doubtful whether the term is very meaningful. [166] [166] Van Wolferen, The Enigma of Japanese Power , p. 29.

Japan may have changed hugely since 1868, but the influence of the past is remarkably persistent.

Following the Meiji Restoration, Japan ’s mission was to close the gap with the West, to behave like the West, to achieve the respect of the West and ultimately to become, at least in terms of the level of development, like the West. Benchmarking and catch-up were the new lodestars. [167] [167] Interview with Yoshiji Fujita, Research Director, Glaxo Japan, June 1999.

Before 1939 this primarily meant Europe, but after 1945 Europe was replaced in the Japanese mind by an overwhelming preoccupation with the United States. In this context, the key objective was economic growth, but Japan ’s colonial expansion, which started within six years of the Meiji Restoration, also owed much to a desire to emulate Europe: to be a modern power, Japan needed to have its own complement of colonies. These territorial ambitions eventually brought Japan to its knees in the Second World War, culminating in its defeat and surrender. It was a humiliating moment: the very purpose of the Meiji Restoration — to prevent the domination of the country by the West — had been undermined. The post-1868 trajectory had resulted in the country’s occupation, its desire to emulate the West in disaster.

Nevertheless, the war was to prove the prelude to the most spectacular period of economic growth in Japan ’s history. In 1952, Japan ’s GDP was smaller than colonial Malaya ’s. Within a generation the country had moved from a primarily agrarian to a fully-fledged industrial nation, achieving an annual per capita growth rate of 8.4 per cent between 1950 and 1970, far greater than achieved elsewhere and historically unprecedented up to that time. By the 1980s, Japan had overtaken both the United States and Europe in terms of GDP per head and emerged as an industrial and financial powerhouse. [168] [168] Wilkinson, Japan Versus the West , pp. 4, 5, 45, 135.

It was an extraordinary transformation, but it was not to be sustained. At the end of the 1980s, Japan ’s bubble economy burst and for the following fifteen years it barely grew at all. Meanwhile, the United States found a new lease of economic life, displaying considerable dynamism across a range of new industries and technologies, most notably in computing and the internet. Japan ’s response to this sharp downturn in its fortunes was highly instructive — both in terms of what it said about Japan and about the inherent difficulties entailed in the process of catch-up for all non-Western societies.

The apogee of Japan ’s post-1868 achievement — the moment that it finally drew level with and overtook the West during the 1980s [169] [169] By 1980, Japan had more or less drawn level with the European Community and the United States in terms of GDP per head, and during the 1980s pulled well ahead by this measure; ibid., p. 5.

— carried within it the seeds of crisis. Ever since 1868, Japan ’s priority had been to catch up with the West: after 1945 this ambition had become overwhelmingly and narrowly economic. But what would happen when that aim had finally been achieved, when the benchmarking was more or less complete, when Japan had matched the most advanced countries of the West in most respects, and in others even opened up a considerable lead? When the Meiji purpose had been accomplished, what was next? Japan had no answer: the country was plunged into an existential crisis. It has been customary to explain Japan ’s post-bubble crisis in purely economic terms, but there is also a deeper cultural and psychological explanation: the country and its institutions, including its companies, quite simply lost their sense of direction. [170] [170] Interview with Yoshiji Fujita, Research Director, Glaxo Japan, June 1999. As Takamitsu Sawa has written: ‘Drunk with joy for having realised a major goal, the Japanese were at a loss to define the next goal. Suffering from a sense of despair they wasted the next decade.’ ‘ Japan ’s Paradox of Wealth’, Japan Times , 30 May 2005.

Читать дальше