It has become evident that China is prepared to take a more proactive and interventionist role in international financial affairs. Given that the global financial crisis is presently at the top of every agenda and that reform of the existing global financial order is now irresistible, this has far-reaching implications: China will be a central player in whatever new architecture emerges from the present crisis. This represents an extraordinary change even compared with two years ago, let alone five years ago, when China was not even included in discussions on such matters. But it also has a much wider significance. The rise of China and the decline of the United States will, at least during this period, be enacted overwhelmingly on the financial and economic stage. And China is demonstrating that it intends to be a full-hearted participant in this process. It is not difficult to predict some of the likely consequences: the G20 will effectively replace the G8 and the IMF and the World Bank will be subject to reform, with the developing countries acquiring a greater say.

The most audacious proposal that has so far emanated from Beijing is the suggestion for a new de facto global currency based on using IMF’s special drawing rights, which might in time replace the dollar as the world’s reserve currency. Whether such a proposal would ever see the light of day, or indeed work, given that reserve currencies hitherto have always depended on a powerful sovereign state, it offers an insight into the strategic financial thinking that informs the Chinese government’s approach. It suggests that the Chinese recognize that the days of the dollar as the dominant global currency are now numbered. At the same time, the Chinese government is actively seeking ways to progressively internationalize the role of the renminbi. It recently concluded a number of currency swaps with major trading partners including South Korea, Argentina and Indonesia, thereby widening the use of the renminbi outside its own borders. It is also in the process of taking steps to increase the renminbi’s role in Hong Kong, which is significant because of the latter’s international position, and has announced its intention of making Shanghai a global financial centre by 2020. There are, thus, already strong indications that China ’s rise will be hastened by the global crisis.

Appendix — The Overseas Chinese

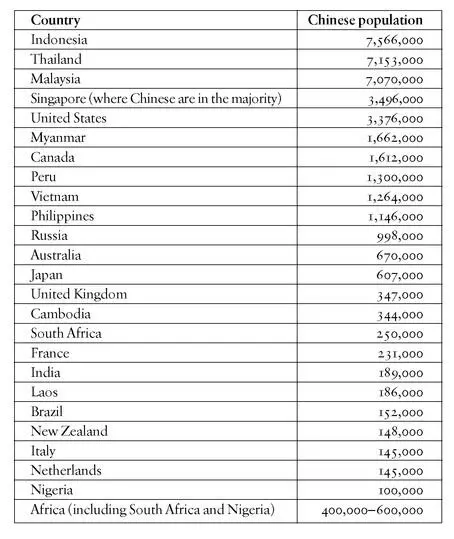

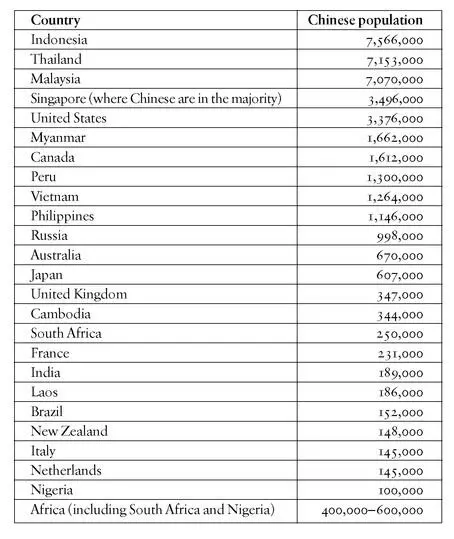

For a number of reasons it is difficult to estimate the number of overseas Chinese. In some instances, migration remains highly active, for example to Africa and Australia. There are also problems of definition as to precisely who the category should include, those of mixed race being an obvious example. The statistics also vary greatly in their reliability and accuracy for various reasons, including illegal immigration, the quality of censuses and definitional issues. Notwithstanding these difficulties, the table below gives a rough idea of the total size of the Chinese diaspora and the main countries where it resides.

Chinese migration has a long history, dating back to the Ming dynasty in the case of South-East Asia. The global Chinese diaspora began in the nineteenth century, when there was a surplus of labour in the southern coastal provinces of China and Chinese workers were recruited for the European colonies, often as indentured labour. The biggest migratory movements were to South-East Asia, but the Chinese also went in large numbers during the second half of the nineteenth century to the United States, notably in search of gold and to build the railroads, and also to Australia and many other parts of the world including Europe and South Africa. Over the period 1844-88 alone over 2 million Chinese found their way to such diverse locations as the Malay Peninsula, Indochina, Sumatra, Java, the Philippines, Hawaii, the Caribbean, Mexico, Peru, California and Australia. In the second half of the twentieth century there has been a big expansion in Chinese migration to North America, Australia and, very much more recently, Africa, as well as elsewhere.

There is a voluminous literature on the subject, including: Lynn Pan, ed., The Encyclopedia of the Chinese Overseas (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999); Lynn Pan, Sons of the Yellow Emperor: The Story of the Overseas Chinese (London: Arrow, 1998); Robin Cohen, Global Diasporas: An Introduction (London: UCL Press, 1997); Susan Gall and Ireane Natividad, eds, The Asian American Almanac: A Reference Work on Asians in the United States (Detroit: Gale Research, 1995); Wang Gungwu, China and the Chinese Overseas (Singapore: Times Academic Press, 1991); Wang Lingchi and Wang Gungwu, eds, The Chinese Diaspora: Selected Essays , 2 vols (Singapore: Times Academic Press, 1998); Wang Gungwu, The Chinese Overseas: From Earthbound China to the Quest for Autonomy (London and Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2000).

It is difficult, a little invidious even, to select a relative handful of books from the vast range of sources — including books, academic and newspaper articles, lectures, talks, seminars, personal conversations, conference proceedings and countless interviews — that I have used in writing this book. Nonetheless, having spent years burrowing away, I feel it is my responsibility to offer a rather more selective list of books for the reader who might want to explore aspects of the subject matter a little further. I cannot provide any titles that offer the same kind of sweep as this book but no doubt in due course, as China ’s rise continues, there will be several and eventually a multitude.

I have mainly used three general histories of China, though others have been published more recently. The best is John King Fairbank and Merle Goldman, China: A New History (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006), but I also found Jonathan D. Spence, The Search for Modern China , 2nd edn (New York: W. W. Norton, 1999), and Jacques Gernet, A History of Chinese Civilization , 2nd edn (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), very useful. Julia Lovell, The Great Wall: China against the World 1000 BC - AD 2000 (London: Atlantic Books, 2006), is a highly readable account of the Wall as a metaphor for the long process of China’s expansion, while Peter C. Perdue, China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005), is a formidable account of the huge expansion of Chinese territory that took place under the Qing dynasty. Edward L. Dreyer, Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405 - 1433 (New York: Pearson Longman, 2007), examines one of the most remarkable achievements in Chinese history. Although Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs and Steel: A Short History of Everybody for the Last 13,000 Years (London: Vintage, 1998), only has a little about China, in a few short pages he demonstrates just how untypical Chinese civilization is in the broader global story.

There are many books that deal with Europe’s rise and the failure of China to industrialize from the end of the eighteenth century. Kenneth Pomeranz, The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2000), and R. Bin Wong, China Transformed: Historical Change and the Limits of European Experience (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2000), have been amongst the most prominent recently in arguing that Europe’s rise was largely a consequence of contingent factors; Pomeranz’s book has become a key book in this context. Mark Elvin, The Pattern of the Chinese Past (London: Eyre Methuen, 1973), still remains essential reading for those seeking an explanation of why China lost out on industralization. I also found C. A. Bayly, The Birth of the Modern World 1780 - 1914: Global Connections and Comparisons (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004), by taking a global frame of reference, useful in arriving at a broader picture.

Читать дальше