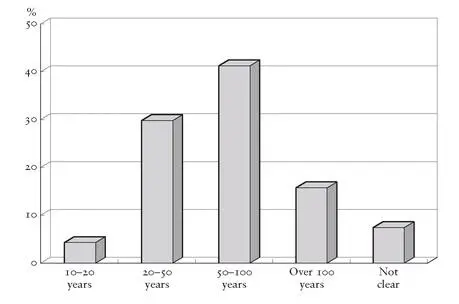

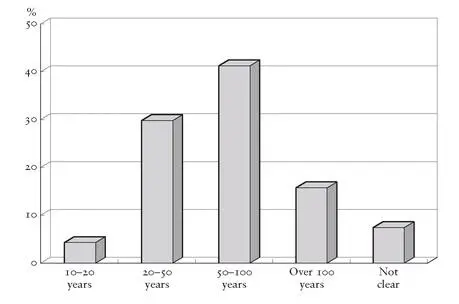

Figure 47. Response of Chinese youth to the question, ‘How many years do you believe it will take for China’s comprehensive national power to catch up with Western developed nations?’

It has been argued that Chinese military doctrine — stemming from the ancient military strategist Sun Zi (who lived c . 520–400 BC, just before the Warring States period) and others — sets much greater store on seeking to weaken and isolate the enemy rather than in actually fighting him: that force, in effect, should be a last resort and that its actual use is a sign of weakness rather than strength. As Sun Zi wrote, ‘Every battle is won or lost before it is ever fought.’ This is certainly a very important strand in Chinese strategic culture, [1286] [1286] Callahan, Contingent States , pp. 34-7.

but it would be misleading, argues the international relations expert Alastair Iain Johnston, to regard this, rather than the contrary view that conflict is a constant feature of human affairs, as the dominant element in Chinese history. He writes: ‘My analysis of the Seven Military Classics [the seven most important military texts of ancient China, including Sun Zi’s The Art of War ]… shows that these two paradigms cannot claim separate but equal status in traditional Chinese strategic thought. Rather the parabellum paradigm [that war is essential] is, for the most part, dominant.’ [1287] [1287] Johnston, Cultural Realism , p. 249.

His view has been strongly contested by Chinese scholars, however. [1288] [1288] Callahan, Contingent States , pp. 34- 5.

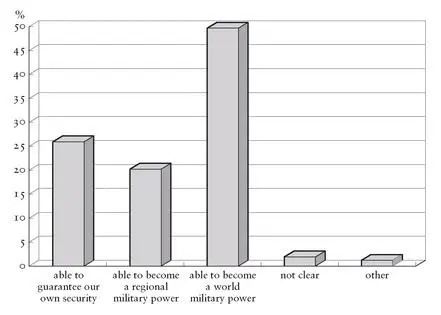

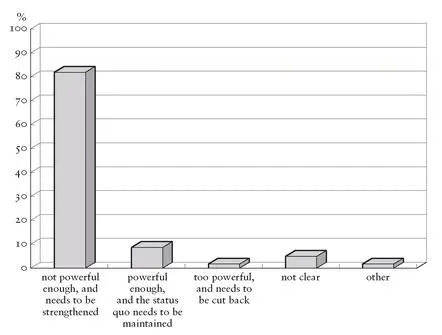

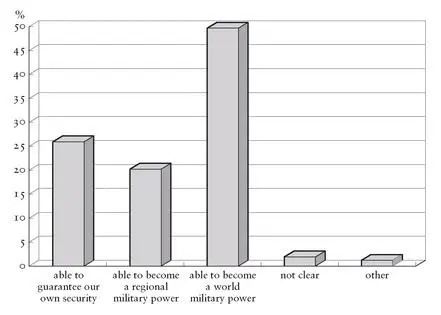

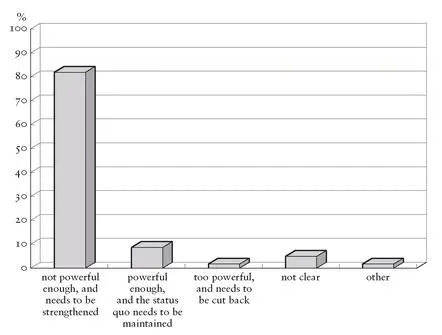

Whichever view is correct, it seems likely that China will in due course acquire a very powerful military capability. In a 2003 survey of over 5,000 students drawn from China ’s elite universities — a potentially significant indicator of future Chinese attitudes — 49.6 per cent believed that China in future should become a world military power, while 83 per cent felt that Chinese military power was inadequate (see Figures 48 and 49). [1289] [1289] Wang Xiaodong, Chinese Youth’s Views on the World: A Survey Report (Beijing: China Youth Research Centre, 2003), pp. 27-8.

What conclusions might we draw? For perhaps the next half-century, it seems unlikely that China will be particularly aggressive. History will continue to weigh very heavily on how it handles its growing power, counselling caution and restraint. On the other hand, as China becomes more self-confident, a millennia-old sense of superiority will be increasingly evident in Chinese attitudes. But rather than being imperialistic in the traditional Western sense — though this will, over time, become a growing feature as it acquires the interests and instincts of a superpower — China will be characterized by a strongly hierarchical view of the world, embodying the belief that it represents a higher form of civilization than any other. This last point should be seen in the context of historian Wang Gungwu’s argument that, while the tributary system was based on hierarchical principles, ‘more important is the principle of superiority’. [1290] [1290] Wang Gungwu, ‘Early Ming Relations with Southeast Asia: A Background Essay’, in John King Fairbank, ed., The Chinese World Order: Traditional China’s Foreign Relations (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1968), p. 61.

This combination of hierarchy and superiority will be manifest in China ’s attitude towards East Asia and also, one strongly suspects, in a variegated way towards other continents and countries, notably Africa. Wang Gungwu suggests that even when China was forced to abandon the tributary system and adapt to the disciplines of the Westphalian system, in which all states enjoyed formal equality, China never really believed that this was the case. ‘This doubt partly explains,’ argues Wang Gungwu, ‘the current fear that, when given the chance, the Chinese may wish to go back to their long-hallowed tradition of treating foreign countries as all alike but equal and inferior to China [my italics].’ [1291] [1291] Ibid., p. 61.

Figure 48. Response of Chinese youth to the question, ‘Do you hope that China ’s future military power is… ’

Figure 49. Response of Chinese youth to the question, ‘Do you believe our military power is… ’

The size of its population and the longevity of its civilization mean that China will always have a different attitude towards its place in the world from Europe or the United States. China has always constituted itself as, and believed itself to be, universal. That is the meaning of the Middle Kingdom mentality. In an important sense, China does not aspire to run the world because it already believes itself to be the centre of the world, this being its natural role and position. And this attitude is likely to strengthen as China becomes a major global power. As a consequence, it may prove to be rather less overtly aggressive than the West has been, but that does not mean that it will be less assertive or less determined to impose its will and leave its imprint. It might do this in a different way, however, through its deeply held belief in its own inherent superiority and the hierarchy of relations that necessarily and naturally flow from this.

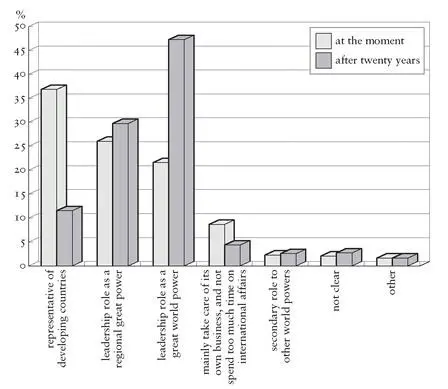

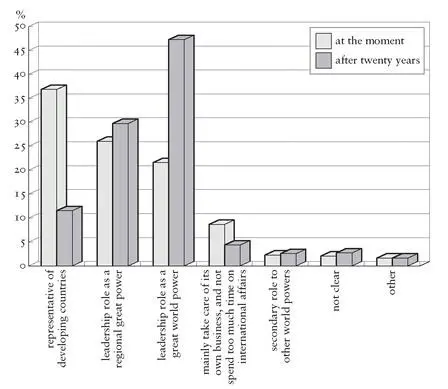

Figure 50. Response of Chinese youth to the question, ‘What role do you think China should play in international affairs?’

Although the West finds it difficult to imagine a serious and viable alternative to its own arrangements, believing that ultimately all other countries, whatever their history or culture, are likely to converge on the Western model, China represents precisely such an alternative. To understand the nature of the Chinese polity — and how it differs from the West — one has to move beyond the present Communist regime and see China in a much longer-term context. Its underlying characteristics, as discussed in Chapter 7, can be summed up as follows: an overriding preoccupation with unity as the dominant imperative of Chinese politics; the huge diversity of the country; a continental size which means that the normal feedback loops of a conventional nation-state do not generally apply; a political sphere that has never shared power with other institutions like the Church or business; the state as the apogee of society, above and beyond all other institutions; the absence of any tradition of popular sovereignty; and the centrality of moral suasion and ethical example. Given the weight of this history, it is inconceivable that Chinese politics will come to resemble those of the West. It is possible, even likely, that in the longer run China will become increasingly democratic, but the forms of that democracy will inevitably bear the imprint of its deeply rooted Confucian tradition. Moreover, rather than seeing the post-1949 Communist regime as some kind of aberration from the norm of Chinese history, in many respects the Communist regime (especially the Deng and post-Deng era — more than the Maoist years) lies within the national tradition.

Читать дальше