This makes the second scenario — India being obliged to live with and adapt to China ’s power and presence in South Asia — rather more probable. It also increases the likelihood that China will emerge over time not only as the dominant power in East Asia but in South Asia as well. There is, however, an important rider to this, as the rules of the game appear to be chang-ing in a significant way. During the second term of the Clinton administration, the United States established a strategic partnership with India which was extended in 2006 by the Bush administration to include nuclear cooperation, an agreement which was eventually approved by the Indian parliament in 2008. [1129] [1129] Gideon Rachman, ‘Welcome to the Nuclear Club, India ’, Financial Times , 22 September 2008.

The agreement violated previous American policy by accepting India ’s status as a nuclear power, even though it was not a signatory to the Non-Proliferation Treaty. This was a pointed reminder that US policy on nuclear proliferation is a matter of interest and convenience rather than principle, as the contrasting cases of Iran and Israel in the Middle East also illustrate. The reason for the American volte-face was geopolitical, the desire to promote India as a global power and establish a new US- India axis in South Asia as a counter to the rise of China. [1130] [1130] Jo Johnson and Edward Luce, ‘ Delhi Nuclear Deal Signals US Shift’, Financial Times , 2 August 2007.

During the Cold War relations between India and the US were distant and distrustful, and even after 1989 they improved little, with the US pursuing an even-handed approach to India and Pakistan and imposing sanctions on India after its nuclear tests in 1998. It is testimony to the growing American concern about China that the US was persuaded to engage in such a U-turn. For its part, India ’s position had previously been characterized by its relative isolation: apart from its long-standing alliance with the former Soviet Union, its determinedly non-aligned status had led it to resist forming strategic partnerships with the major powers or even second-tier ones. [1131] [1131] Garver, Protracted Contest , pp. 376-7.

But there is unease amongst sections of the Indian establishment, especially the military, about China ’s growing power. [1132] [1132] Charles Grant, ‘ India ’s Role in the New World Order’, Centre for European Reform Briefing Note (September 2008).

Depending on how the US- India partnership evolves, it could dramatically change the balance of power between China and India in South Asia, persuading China to act more cautiously while at the same time emboldening India. [1133] [1133] Roger Cohen, ‘Nuclear Deal With India a Sign of New US Focus’, International Herald Tribune , 4–5 March 2006; Rajan Menon and Anatol Lieven, ‘Overselling a Nuclear Deal’, International Herald Tribune , 7 March 2006; John W. Garver, ‘China’s Influence in Central and South Asia: Is It Increasing?’, in Shambaugh, Power Shift , p. 223.

The US-India partnership raises many questions and introduces numerous uncertainties. If it proves effective and durable, then it could act as a significant regional and global counter to China. How China will respond remains to be seen: the most obvious move might be a closer relationship with Pakistan, but it is not inconceivable that China might decide to seek a strategic rapprochement with India as a means of fending off the United States and denying it a major presence in South Asia.

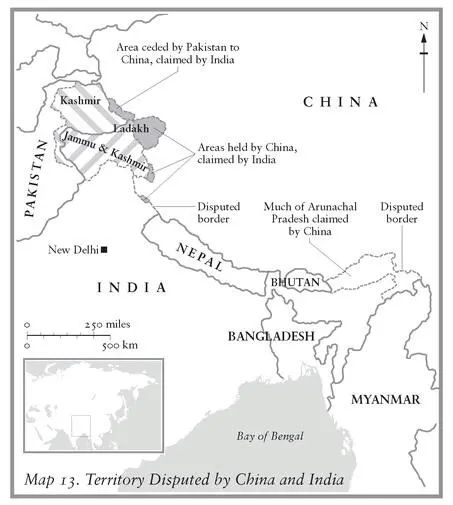

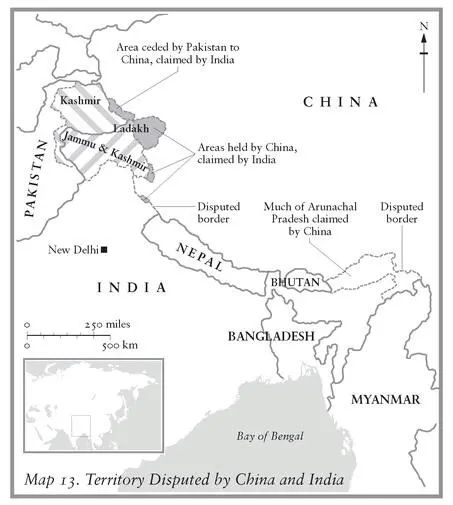

Map 13. Territory Disputed by China and India

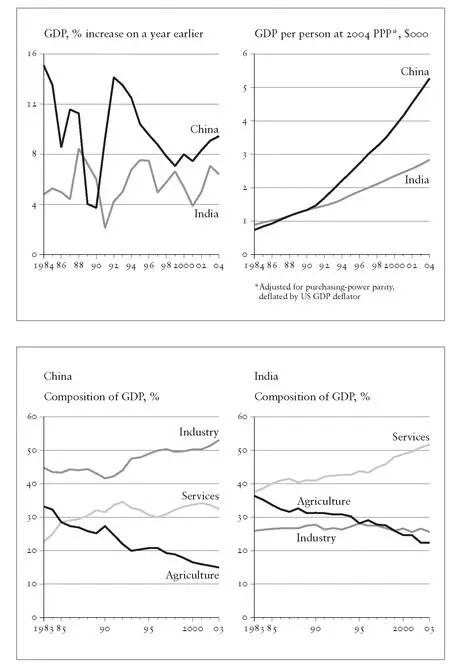

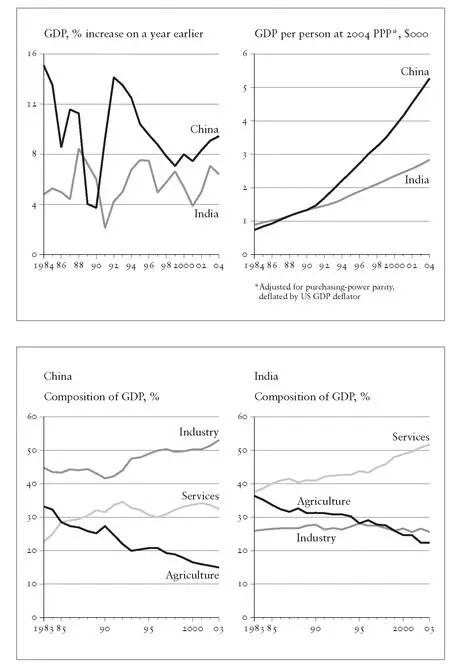

Figure 39. Comparative economic performance of China and India.

China ’s relationship with Europe is significantly different from that with the United States. While the US- China relationship has been a more or less continuous source of domestic debate and controversy, the Europe-China relationship has, until recently, attracted relatively little attention. Relations between Europe and China have hitherto been relatively straightforward and conflict-free. Historically this is a little ironic. After all, it was the European powers, starting with Britain and the Opium Wars, which colonized China, with the United States very much a latecomer to the process. The ‘century of humiliation’ was about Europe, together with Japan, with the United States playing no more than a bit part. The present relationship between Europe and China has been low profile largely because Europe, apart from its economic interests, is no longer a major power in East Asia, a position it relinquished to the United States in the aftermath of the Second World War. That Europe is largely invisible in such an important region of the world bears testimony to its post-1945 global decline and its retreat into an increasingly regional role, a process which continues apace and is likely to accelerate with the rise of China and India. [1134] [1134] Dominique Moisi, ‘Europe Must Not Go the Way of Decadent Venice ’, Financial Times , 12 July 2005.

With the exception of the euro, discussion of Europe ’s wider global role is largely confined to what is known as ‘normative power’, namely the promotion of standards that are negotiated and legitimized within international institutions. [1135] [1135] For example, Zaki Laïdi, ‘How Europe Can Shape the Global System’, Financial Times , 30 April 2008.

Nonetheless, with an economy rivalling that of the United States in size, together with the fact that it forms the other half of the Western alliance, Europe’s attitude towards China is clearly of some importance.

For the most part, Europe’s response to the rise of China has been low-key, fragmented and incoherent. This is because the European Union lacks the power and authority to act as an overarching centre in Europe’s relations with nations such as China. As a result, Europe generally speaks with a weak voice and more often than not with many voices. The European Union is not a unitary state with the capacity to think and act either strategically or coherently, but an amalgam and representative of different interests. [1136] [1136] Katinka Barysch with Charles Grant and Mark Leonard, Embracing the Dragon: The EU’s Partnership with China (London: Centre for European Reform, 2005), p. 77.

Europe’s economic relationship with China has grown enormously over the last decade, with a massive increase in imports of cheap Chinese manufactured goods and a very large rise in European exports to China, mainly of relatively high-tech capital goods, especially from Germany. This has resulted in a growing European trade deficit with China as well as a loss of jobs in those industries that compete directly with Chinese imports. Until recently this has aroused very little political debate, certainly nothing like that in the United States. There are several reasons for this. Europe’s trade deficit with China has been much smaller than the US ’s, although this is now changing. Political attention is centred not so much on Europe ’s deficit but on that of individual countries, and even these have so far attracted relatively little concern. In contrast to the United States, there has been little debate about the exchange rate between the renminbi and the euro, though the appreciation of the euro against the renminbi prior to the global recession led to growing European anxiety and representations to Beijing about the need for a revaluation of their currency. Finally, Europe has been overwhelmingly preoccupied with the effects of the recent enormous enlargement of the EU, not least the large-scale migration of workers from Eastern and Central Europe to Western Europe, [1137] [1137] Ibid., pp. 44-5.

which has had a much greater impact, and certainly been more politically sensitive, than China.

Читать дальше