“Is he talking about me?” I asked my parents.

My mom nodded. “I think so.”

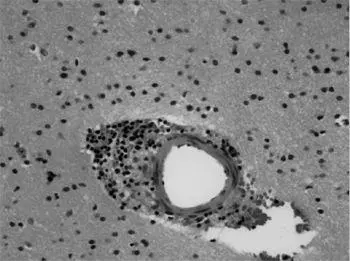

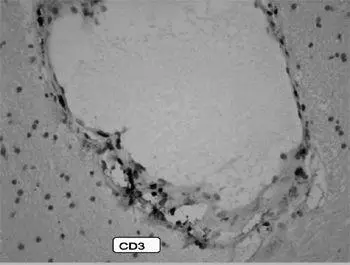

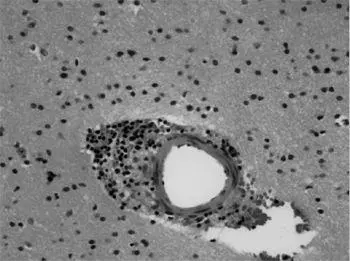

Dr. Najjar cut to a magnified picture of a biopsied brain sample. It was stained mauve with bluish-purple spots surrounding a blood vessel. The dark spots, he explained, were inflammatory microglia cells.

“He’s talking about my brain,” I whispered, although I didn’t understand then what these slides portrayed. All I knew was that a very intimate part of myself was on display in front of a hundred strangers. How many people can say that they’ve allowed others to literally see inside their heads? I touched my biopsy scar as Dr. Najjar continued to talk about my brain tissue.

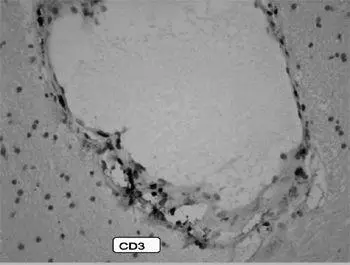

He then clicked through to another slide, one that looked like a delicate, chain-link necklace covered with lilac and agate gemstones swooping down in a U shape.

Dr. Najjar explained that the brain biopsy picture showed a blood vessel under attack by lymphocyte cells. As he pointed out, however, there have been only a handful—ten or fewer—of brain biopsies conducted in those with anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis, so these slides offer a rare and informative look at a sick brain we know very little about.

He ended the lecture with a final statement: “I’m proud to say that this patient is back to normal and is currently back to work at the New York Post.”

Angela nudged me, Lauren smiled, and Stephen and my parents glowed.

When we got back to the office that day, Angela mentioned the presentation to our editors, Steve and Paul. Steve was intrigued and called me into his office.

“Angela tells me that she went to a meeting on your illness,” Steve said. “Would you be willing to write a first-person piece about it?”

I nodded emphatically. I had been hoping my editors would find my story interesting enough for an article, and I was eager to finally indulge my reporting instincts and buckle down to research it.

“Great. Can you get it to us by Friday?”

Today was Tuesday. Friday felt soon, but I was determined to make it happen. It was thrilling, if somewhat frightening and dizzying, to think of sharing those confusing months with the world. Most of my colleagues were still in the dark about what had happened during my extended absence (as, in a sense, was I), and it worried me to think that this story might undo everything I had accomplished in presenting myself as a professional over the past few weeks back at work. But it was irresistible: Now I had the opportunity to uncover that lost time and prove to myself that I could understand what had happened inside my body.

With those conflicting feelings percolating in my mind, I placed my reporter’s cap firmly back on and interviewed my family, Stephen, Dr. Dalmau, and Dr. Najjar to get a portrait of my disease and its larger-scale implications.

What I was almost immediately drawn to is perhaps the biggest mystery: How many people throughout history suffered from my disease and others like it but went untreated? This question is made more pressing by the knowledge that even though the disease was discovered in 2007, some doctors I spoke to believe that it’s been around at least as long as humanity has.

In the late 1980s, French Canadian pediatric neurologist Dr. Guillaume Sébire noticed an unusual pattern among six children he treated from 1982 to 1990. 51They all had movement disorders, including involuntary tics or excessive restlessness, cognitive impairments, seizures, normal CT scans, and negative blood work results. The children were diagnosed with “encephalitis of an unknown origin” (or what was colloquially known as the Sébire syndrome), a disease that lasted on average ten months. Four of the six children made what could be called a full recovery. His hazy description of the disease persisted for another two decades.

An earlier paper, written in 1981 by Robert Delong and colleagues, described “acquired reversible autistic syndrome” in children. 52The disease presented like autism, but two of the three children studied (a five-year-old girl and a seven-year-old boy) recovered fully, while an eleven-year-old girl continued to endure severe memory and cognitive deficits, unable to remember three words provided to her after only a few minutes had elapsed. Now, studies show that roughly 40 percent of patients diagnosed with this disease are children (and this percentage is growing), but children present the disease differently from adults: afflicted children exhibit behaviors such as temper tantrums, mutism, hypersexuality, and violence. 53One parent described how her child tried to strangle her infant sibling; another heard low grunting noises from their normally angelic daughter; and another child clawed at her own eyes to communicate the inner turmoil that her toddler vocabulary could not convey. The disease in children has often been misdiagnosed as autism, but depending on where and when the person lived, it might have been described as supernatural, even something evil.

Evil. To the untrained eye, anti-NMDA-receptor autoimmune encephalitis can certainly appear malevolent. Afflicted sons and daughters suddenly became possessed, demonic, like creatures out of our most appalling nightmares. Imagine a young girl who, after several days of full-bodied convulsions that sent her flying into the air and off her bed—and after speaking in a strange, deep baritone—contorted her body and crab-walked down the staircase, hissing like a snake and spewing blood.

This chilling scene is, of course, from the unedited version of the blockbuster film The Exorcist, and though fictionalized, it depicts many of the same behaviors that children suffering from anti-NMDA-receptor autoimmune encephalitis do. The image is not as exaggerated as we might think. (Stephen, for one, can no longer watch The Exorcist ; it brings him right back to those strange “panic attacks” I experienced in the hospital, and to my first seizure as we watched TV on the pullout couch.) In 2009, a thirteen-year-old girl from Tennessee displayed a “range of emotions and symptoms that varied by the hour, at times mirroring schizophrenia, and, at other times, autism or cerebral palsy.” 54She lashed out violently and would bite her tongue and mouth. She once insisted on crab-walking across the hospital floor. She also spoke in a bizarre, Cajun-inflected accent, according to the Chattanooga Times Free Press , which detailed her experience with anti-NMDA-receptor autoimmune encephalitis and subsequent recovery.

Many parents report that their children start speaking in a garbled foreign language or with an unusual accent, just like when the fictional Regan in The Exorcist begins to speak fluent Latin with the priest who has come to exorcise her. Likewise, those who suffer from this type of encephalitis will display what is known as echolalia, the repetition of sounds made by another person. 55That would explain the sudden ability to “speak in tongues,” though in real life those who are suffering from the illness typically do so illogically, not fluently.

How many children throughout history have been “exorcised” and then left to die when they did not improve? How many people currently are in psychiatric wards and nursing homes denied the relatively simple cure of steroids, plasma exchange, IVIG treatment, and, in the worst cases, more intense immunotherapy or chemotherapy? Dr. Najjar estimates that 90 percent of people suffering from this disease during the time when I was treated in 2009 went undiagnosed. Although this number is probably decreasing as the disease becomes better known, there are still people who are suffering from something treatable and not receiving the proper intervention. I couldn’t forget how close I had come to such a dangerous edge.

Читать дальше