Gendal asked me to stick out my tongue, which trembled from the effort. It had a reduced range of motion on both sides, which was contributing to my inability to articulate.

“Would you smile for me?”

I tried, but my facial muscles were so weak that no smile came. She wrote down “hypo-aroused,” a medical term for lethargic, and also noted that I was not fully alert. When I did talk, the words came out without any emotional register.

She moved on to cognitive abilities. Holding up her pen, she asked, “What is this?”

“Ken,” I answered. This, again, wasn’t too unusual for someone at my level of impairment. They call it phonemic paraphasia, where you substitute one word for another that sounds similar.

When she asked me to write my name, I painstakingly drew out an “S,” tracing the letter multiple times before moving on to the “U,” where I did the same. It took several minutes for me to write my name. “Okay, would you write this sentence out for me: ‘Today is a nice day.’”

I drew out the letters, retracing each of them several times and misspelling some words. My handwriting was so poor that Gendal could hardly make out the sentence.

She wrote her impression in the chart: “It is difficult to determine at just two days post-operation to what extent communication deficits are language-based versus medication or cognitive. Clearly communication function is dramatically reduced from pre-morbid level when this patient was working as a successful journalist for a local paper.” In other words, there seemed to be a dramatic change between the person I had been and the person I was now, but it was difficult at the time to distinguish my problems understanding from my inability to communicate—and whether these would persist in the long or short term.

Later the next morning, neuropsychologist Chris Morrison arrived with her auburn hair piled high on her head and green-flecked hazel eyes flashing. She was there to test me on something called the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, as well as other tests, that are used to diagnose a number of things, from attention deficit disorder to traumatic brain injuries. But when she entered the room, I was so unresponsive she wasn’t even sure that I could see her.

“What is your name?” Dr. Morrison began brightly, walking me through the basic orienting questions that by now I had been conditioned to answer correctly. Her next stage of questions assessed attention, processing speed, and working memory, which she compared to a computer’s random access memory (RAM), as in, “How many programs you can have open all at once—how many things you can keep in your head at once and spit back out.”

Dr. Morrison provided me with a random assortment of single-digit numbers, 1 through 9, and asked me to repeat them to her. Once we got up to five digits, I had to stop, though seven is the normal limit for people of my age and intelligence.

Next, she tested the word-retrieval process, to see how well I was able to access my “memory bank.” “I’d like you to name as many fruits and vegetables as possible,” she said, starting a sixty-second timer.

“Apples,” I began. Apples are a common fruit to start with, and of course they had been on my mind a lot lately.

“Carrots.”

“Pears.”

“Bananas.”

Pause.

“Rhubarb.”

Dr. Morrison chuckled inwardly at this one. The minute was over. I had come up with five fruits and vegetables; a healthy individual could name over twenty. Dr. Morrison believed that I knew plenty more examples; the problem seemed to be retrieving them.

She then showed me a series of cards with everyday objects on them. I could name only five of the ten, missing examples like kite and pliers, though I struggled as if the words were on the tip of my tongue.

Dr. Morrison then tested my ability to view and process the external world. There are many different things that must come together for a person to accurately perceive an object. To see a desk, for example, first we see lines that come together at angles, then color, then contrast, then depth; all of that information goes into the memory bank, which labels it with a word and, depending on the object, an emotion (to a journalist, a desk might elicit guilty feelings about missed deadlines, for example). To track this set of skills, she had me compare the size and shape of various angles. I scored on the low end of average on these, well enough for Dr. Morrison to move on to more difficult tasks. She introduced a set of red and white blocks and placed them on the foldout tray in front of me. She then showed me a picture of how the blocks should be arranged and asked me to re-create the picture with a timer running.

I stared at the pictures and then back at the blocks, moved them into a pattern that had nothing to do with the picture, and looked back at the picture for reference. I fiddled with the blocks some more, getting nowhere, but refused to give up. Morrison wrote down “tenacious in her attempts.” I seemed to realize I wasn’t getting it right, which frustrated me deeply. It was clear that, for all my other impairments, I knew that I was not functioning at the level I was used to.

The next step was for me to copy down complex geometric designs on graph paper, but my abilities here were so weak that Dr. Morrison decided to stop altogether. I was flustered, and she worried that moving forward would only make me feel worse. Dr. Morrison was convinced that I was very much aware, despite the cognitive issues, of what I could no longer do. In her review later that day, she marked cognitive therapy as “highly recommended.”

CHAPTER 31

THE BIG REVEAL

Later that afternoon, my dad had been trying to interest me in a game of gin rummy when Dr. Russo and the team arrived.

“Mr. Cahalan,” she said. “We have some positive test results.”

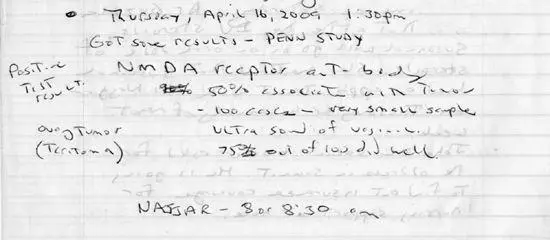

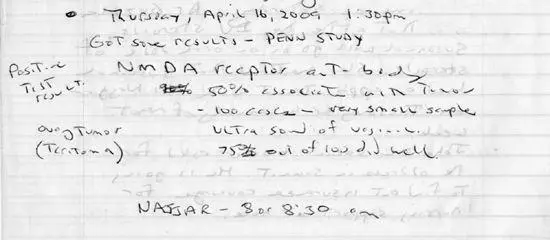

He dropped the playing cards on the floor and grabbed his notebook. Dr. Russo explained that they’d heard back from Dr. Dalmau with a confirmation of the diagnosis. Her words flew at him like shrapnel—bang, bang, bang: NMDA, antibody, tumor, chemotherapy. He fought to pay close attention, but there was one key part of the explanation that he could hold on to: my immune system had gone haywire and had begun attacking my brain.

“I’m sorry,” he interrupted the barrage. “What is the name again?”

He wrote the letters “NMDA” in his block lettering:

Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis, Dr. Russo explained, is a multistage disease that varies wildly in its presentation as it progresses. For 70 percent of patients, the disorder begins innocuously, with normal flulike symptoms: headaches, fever, nausea, and vomiting, though it’s unclear if patients initially contract a virus related to the disease or if these symptoms are a result of the disease itself. 42Typically, about two weeks after the initial flulike symptoms, psychiatric issues, which include anxiety, insomnia, fear, grandiose delusions, hyperreligiosity, mania, and paranoia, take hold. Because the symptoms are psychiatric, most patients seek out mental health professionals first. Seizures crop up in 75 percent of patients, which is fortunate if only because they get the patient out of the psychologist’s chair and into a neurologist’s office. From there, language and memory deficits arise, but they are often overshadowed by the more dramatic psychiatric symptoms.

My father sighed with relief. He felt comforted by a name, any name, to explain what had happened to me, even if he didn’t quite understand what it all meant. Everything she said was matching up perfectly to my case, including abnormal facial tics, lip smacking, and tongue jabbing, along with synchronized and rigid body movements. Patients also often develop autonomic symptoms, she continued: blood pressure and heart rate that vacillate between too high and too low—again, just like my case. She hardly needed to point out that I had now entered the catatonic stage, which marks the height of the disease but also precedes breathing failure, coma, and sometimes death. The doctors seemed to have caught it just in time.

Читать дальше