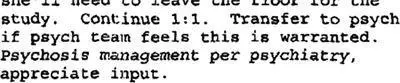

In the interim, Dr. Russo had changed the chief complaint in her daily progress note from “seizures” to “psychosis and possible seizures” and then finally to just “psychosis.” Postictal psychosis had become less of a primary diagnosis because I had not had a seizure since admission. In those with PIP, the psychosis is unlikely to continue unabated or increase in intensity without any seizure activity. Tests for hyperthyroidism, which can cause psychosis, came back negative, but they had to hold off on other tests. I was still far too psychotic for any more invasive examinations.

However, Dr. Russo also added a line in her progress note that had not been there before: “Transfer to psych [ward], if psych team feels this is warranted.” Like Dr. Arslan, she chose not to tell my parents about this new suggestion.

Although many of these findings were kept from my family and me, it was clear that my place on the epilepsy floor was becoming more and more precarious, just as the nurse had warned my father, both because my seizures seemed to have stopped and because I was such a difficult patient. Sensing that attitudes toward me improved and the level of care rose when company arrived, my dad stuck to his promise and started to arrive first thing every morning. Alone, I could not fight this battle.

My mother came every day, during her lunch hours, any breaks she could get from work, and then again after 5:00 p.m. She maintained several running lists of questions, lobbing one after another at the doctors and nurses, relentless even as so many of her questions remained unanswerable. She collected detailed notes, writing down doctors’ names, home numbers, and unfamiliar medical terms she planned to look up. Though they were barely on speaking terms, she and my father also established a journal system so that they could communicate developments with each other when the other was absent. Though it had been eight years since their divorce, it was still hard for them to be in the same room with each other, and this shared journal allowed them to maintain common ground in the shared fight for my life.

Stephen too played a primary emotional role. I’m told that I would visibly relax when he arrived in the room carrying a leather briefcase that was often filled with Lost DVDs and nature documentaries for us to watch together. The second night I was there, though, I clutched his hand and said, “I know this is too much for you. I understand if you don’t come back. I understand if I never see you again.” It was then, he later told me, that he made a pact with himself not unlike my parents’: if I were in the hospital, he would be there too. No one had any idea if I’d ever be myself again, or if I’d even survive this. The future didn’t matter—he cared only about being there for me as long as I needed him. He would not miss even one day. And he didn’t.

The fourth day, doctors number six, seven, eight, and nine joined the team: an infectious disease specialist who reminded my dad of his uncle Jimmy, who had earned the Purple Heart after storming the beaches of Normandy in World War II; an older, gray-haired rheumatologist; a soft-spoken autoimmune specialist; and an internist, Jeffrey Friedman, a spritely man in his early fifties who, despite the severity of the situation, exuded a natural optimism.

Dr. Friedman, who had been summoned to address my high blood pressure, was immediately sympathetic. He had daughters my age. When he walked into the room, he found me unkempt and confused, fidgeting in bed as Stephen, who sat by my side, tried in vain to calm me. I seemed both sluggish and frantic.

Dr. Friedman attempted a basic health history, but I was too paranoid and preoccupied with those “watching me” to talk coherently, so he went ahead and measured my blood pressure. He was alarmed: with a blood pressure reading at 180/100, those numbers alone could cause brain bleeding, stroke, or death. If she were a computer, he thought, we would have to restart her hard drive. He recommended placing me immediately on two different blood pressure medications.

As Dr. Friedman left the room, he identified my dad outside, sitting in the waiting area reading a book. As the two men chatted about what I was like before I’d gotten sick, my father described me as an active kid, a straight A student who made friends easily, who played hard and worked hard. That picture contrasted sharply with the disarrayed young woman Dr. Friedman had just examined. Even so, he looked my dad directly in his eyes and said, “Please stay positive. It will take time, but she will improve.” When Dr. Friedman embraced him, my dad broke down, a brief surrender.

CHAPTER 20

THE SLOPE OF THE LINE

In the few weeks since my strange symptoms had begun, my dad had been spending much more time with me than usual. He was determined to support me as much as possible, but it was taking a toll on him; he had withdrawn from the rest of his life, even from Giselle. Since my breakdown in his apartment, he had also started keeping a daily journal, independent of the one he shared with my mom, not only to try to help him piece together the medical developments but also simply to help himself cope. After my second escape attempt, he wrote a heartbreaking entry about praying that God would take him instead of me.

He remembers in particular one cold, damp, early spring morning, driving to the hospital with Giselle in silence. He knew she would have given anything to help share some of his suffering, but even so, he remained disengaged, bottling up his anguish the way he always had.

At the hospital, he kissed Giselle good-bye and squeezed onto the crowded elevator. It was excruciating taking this trip alongside the fresh-faced new fathers being ferried to the maternity floor, some of whom bounded vigorously off the elevator. Life was just beginning for these people. The next stop was the cardiac floor, full of concerned looks, and then finally it was the twelfth floor: epilepsy. His turn to get off.

As he walked past a wing under renovation, he caught the eye of a middle-aged construction worker, who quickly looked to the floor in embarrassment. Good things were not happening on twelve; everyone knew that. For the past three days, while spending his hours in the temporary, makeshift waiting room, he had been taking stock of the neighboring activity. One particularly sad story was occurring just across the hall, where a young man was recovering after falling down a shaft and sustaining a massive head injury. His elderly parents came every day to see him, but no one seemed hopeful about his recovery. My dad said a quick prayer, pleading with God that my fate would be different from that young man’s, and he breathed deeply as he prepared himself to see what state I was in this morning. I had just been moved to a new, private room, which seemed like a step in the right direction. On his way to my room, he noticed another patient beckoning him over.

“Is that your daughter?” the woman asked, motioning toward my room.

“Yes.”

“I don’t like the things they’re doing to her,” she whispered. “I can’t speak because we’re being monitored.”

There was something odd about this woman, and my father felt himself grow red in the face, embarrassed by the interaction. Still, he couldn’t help but hear the woman out, especially since my own paranoid ravings seemed confirmed by her exhortations. Naturally, he worried about what occurred on the floor in his absence, although he knew deep down that the center was one of the best in the world and that these fears were likely imaginary.

Читать дальше