“Great,” she said, gathering her purse and folding her paper. “We’ll go right away.”

We entered through revolving doors into the busy, recently remodeled lobby of New York University Langone Medical Center. Nurses sprinted by in green scrubs, followed by nurses’ assistants in purple scrubs; doctors in white lab coats chatted at the crossroads of the corridors; the patients, some with bandages, some on crutches, some in wheelchairs, some on gurneys, journeyed past, dead-eyed and unspeaking. There was no way I belonged here.

We found our way to Admitting, which was a group of chairs surrounding a small desk, where a woman dispatched patients to different floors across the gigantic hospital.

“I want coffee,” I said.

My mother looked annoyed. “Really? Now? Fine. But be back right away.” A part of my mom believed the old, responsible me was still in there somewhere, and she simply trusted that I wouldn’t escape. Luckily, this time she was right.

A small stand nearby sold coffee and baked goods. I calmly chose a cappuccino and a yogurt.

“What do you have on your mouth?” my mother asked when I returned. “And why are you smiling like that?”

The strange taste of foam, a mixture of saliva and steamed milk, on my upper lip.

White lab coats.

The hospital’s cold floor.

“She’s having a seizure!” My mom’s voice echoed across the vast hallway as three doctors descended on my shaking body.

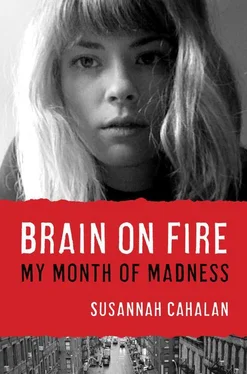

From here on, I remember only very few bits and pieces, mostly hallucinatory, from the time in the hospital. Unlike before, there are now no glimmers of the reliable “I,” the Susannah I had been for the previous twenty-four years. Though I had been gradually losing more and more of myself over the past few weeks, the break between my consciousness and my physical body was now finally fully complete. In essence, I was gone. I wish I could understand my behaviors and motivations during this time, but there was no rational consciousness operating, nothing I could access anymore, then or now. This was the beginning of my lost month of madness.

PART TWO

THE CLOCK

What is today’s date?

Who is the President?

How great a danger do you pose, on a scale of one to ten?

What does “people who live in glass houses” mean?

Every symphony is a suicide postponed, true or false?

Should each individual snowflake be held accountable for the avalanche?

Name five rivers.

What do you see yourself doing in ten minutes?

How about some lovely soft Thorazine music?

If you could have half an hour with your father, what would you say to him?

What should you do if I fall asleep?

Are you still following in his mastodon footsteps?

What is the moral of “Mary Had a Little Lamb”?

What about his Everest shadow?

Would you compare your education to a disease so rare no one else has ever had it, or the deliberate extermination of indigenous populations?

Which is more puzzling, the existence of suffering or its frequent absence?

Should an odd number be sacrificed to the gods of the sky, and an even to those of the underworld, or vice versa?

Would you visit a country where nobody talks?

What would you have done differently?

Why are you here?

FRANZ WRIGHT, “Intake Interview,”

Wheeling Motel

CHAPTER 15

THE CAPGRAS DELUSION

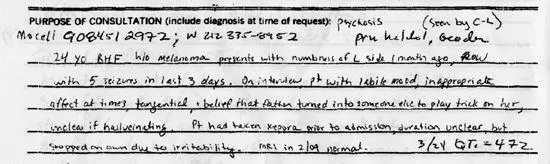

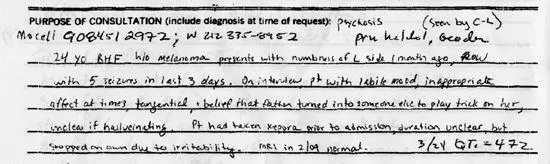

Iwas admitted in midafternoon on March 23, ten days after that first blackout while watching the PBS show with Gwyneth Paltrow. The NYU Langone Medical Center has one of the largest epilepsy units in the world, but the only bed available on the eighteen-patient floor was in the advanced monitoring unit (AMU), a four-person room dedicated to “grid patients,” people with severe epilepsy who need electrodes implanted in their brains so that the center can record the electrical activity required before some types of epilepsy surgery. Occasionally other patients, like me, ended up here due to lack of space. The room has its own nurses’ station, where a staff member monitors the patients twenty-four hours a day. Two cameras hang above each bed, constantly surveying every patient on the floor so that the hospital can have physical as well as electrical evidence of seizures (when a patient is discharged, most of the footage is discarded; the hospital keeps only the seizure events and abnormal circumstances). All of this surveillance would prove essential to me later, when I began to try to reconstruct what happened to me during these lost weeks.

After my seizure in the lobby’s admitting area, my mother and stepfather trailed behind the gurney as the medic team wheeled me onto the epilepsy floor. Two different nurses then brought me into the AMU. Diverted by their new roommate, the room’s three other patients quieted when I arrived. The nurse practitioner took down my health history, noting that I was cooperative with just a hint of delay, which she figured was related to the aftermath of the seizure. When I was unable to answer questions, my mother, clutching her folder full of documents, answered in my stead.

The nurses settled me onto a bed that had two precautionary side guardrails; the bed itself was lowered as close as possible to the ground. Nurses began to arrive approximately once an hour to get my vitals: blood pressure, pulse, and the results of a basic neurological exam. My weight was on the low side of normal, my blood pressure high-normal, and my pulse slightly accelerated but not alarmingly so, given the circumstances. The assessments, which covered everything from bowel movements to level of consciousness, were all normal.

An EEG technician interrupted the screening, pulling a cart behind him. He began unloading handfuls of the multicolored electrodes—reds, pinks, blues, and yellows—like the ones from my EEG at Dr. Bailey’s office. The wires fed into a small, gray EEG box, similar in shape and size to a wireless Internet router, which connected to a computer that would record my brain waves. These electrodes measure the electrical activity along the scalp, tracking the chatter of electrically charged neurons and translating their actions as waves of activity.

As the technician began to apply the adhesive, I stopped cooperating. It took him half an hour to place the twenty-one electrodes as I squirmed. “Please, stop!” I insisted, thrashing my arms as my mother caressed my hands, trying ineffectually to calm me. I was acting even more mercurial than in recent days. Things seemed to be going downhill fast.

Eventually my tantrum receded, but I continued to cry as the smell of fresh glue permeated the air. The tech finished applying the wires and, before he left, handed me a small pink backpack that looked as if it belonged to a preschooler. It held my little “Internet router,” which would allow me to walk around but remain connected to the EEG system.

It was already clear that I would not be an easy patient, given the way I screamed at visitors and lashed out at nurses during those first few hours on the floor. When Allen arrived, I pointed and yelled at him, insisting that the nurses “get this man out of my room.” Similarly, I loudly accused my dad of being a kidnapper when he arrived, and I demanded that they bar him as well. Because I was still in the midst of what seemed to be psychosis, many tests were impossible to conduct.

Читать дальше