—

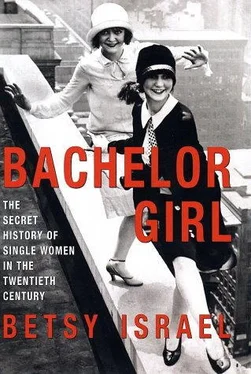

Vanity Fair

“What a read! At long last, a book that really tells it like it is. I loved it!”

—Liz Smith

“A lively history of single women, shifting between the facts of women’s lives and their representation in the media…. Fascinating.”

—

Boston Globe

“A must-read for contemporary bachelor girls. Israel’s insightful study examines the plight of the single woman as a social phenomenon from the mid-1900s to the present.”

—

Booklist

“Betsy Israel explores, in a thoughtful and entertaining style, why society persists in finding nonconforming women both threatening and perplexing.”

—

Elle (Canada)

“Required reading!”

—

New York Post

“Betsy Israel’s social history covers everything from 1920s flappers to 1970s career girls, with wit and style. A must-read for feminists with a sense of humor.”

—

Marie Claire

“Single women are still designated as different from the other kind, not a group any single figure is particularly comfortable to be signed up with. What is this categorizing about? Betsy Israel’s brilliant new book takes us through a century of ‘different-ness’ and explores why it might be extant.”

—Helen Gurley Brown, former

Cosmopolitan editor in chief and author of

Sex and the Single Girl

“[ Bachelor Girl ] is not one history but two: an examination of popular perceptions about single women since the Industrial Revolution paired with the lesser-known truth about how women actually inhabited their roles…. Engaging, convincing, even stirring.”

—

Kirkus Reviews

“Israel has an easy journalistic style and clips along at a good pace. She coins some witty phrases—‘the Cult of Independence’—and often breaks for the ironic aside…. An intriguing balance of cultural history and pointed detail.”

—

San Francisco Chronicle

“ Bachelor Girl takes a revealing look at just how far the single woman has come. For those girls and the country’s women in general, Bachelor Girl serves as a reminder, as well as a yardstick: You may have come a long way, but don’t forget the hardy souls who made it possible.”

—

BookPage

“Impressive…. Israel’s witty and provocative look at a topic dear to many women deserves wide readership.”

—

Publishers Weekly

“You can take all the glowing adjectives you know, lay them in a row, and still not have enough to accurately describe this 294-pager that will make your heart sing.”

—

Massachusetts Post-Gazette

“Betsy Israel’s Bachelor Girl is the history of women in the U.S.”

—

More magazine Book Pick

Images not available for electronic edition.

BACHELOR GIRL. Copyright © 2002 by Elizabeth Israel. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Adobe Digital Edition April 2009 ISBN 978-0-06-194074-3

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Australia

HarperCollins Publishers (Australia) Pty. Ltd.

25 Ryde Road (PO Box 321)

Pymble, NSW 2073, Australia

http://www.harpercollinsebooks.com.au

Canada

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

55 Avenue Road, Suite 2900

Toronto, ON, M5R, 3L2, Canada

http://www.harpercollinsebooks.ca

New Zealand

HarperCollinsPublishers (New Zealand) Limited

P.O. Box 1

Auckland, New Zealand

http://www.harpercollins.co.nz

United Kingdom

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

77-85 Fulham Palace Road

London, W6 8JB, UK

http://www.harpercollinsebooks.co.uk

United States

HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

10 East 53rd Street

New York, NY 10022

http://www.harpercollinsebooks.com

Some early feminists pointed out that the numbers needed interpretation. Women lived longer because, never soldiers or bar brawlers, they often kept their bodies intact past age thirty. They didn’t leave home as often as men, meaning that when census inspectors called, they were in. There also now simply seemed to be more women, because so many formerly hidden middle-class women were out on the streets.

Some single women headed west—by themselves. The Oregon Land Donation Act of 1850 was originally intended to entice spinsters and younger women to come west and marry homesteaders. Changes to the law during the next decade allowed several hundred women to stake land claims of their own.

There were a few categories of spinster exemption. For example, if a woman had lived a privileged life on the stage or been a famous painter’s model or dancer, she would be presumed to possess a stage trunk full of romantic stories forever putting her out of the banal spinster category. The other “out” was the widow-manqué, the spinster who had been engaged to a brave soldier, dead in battle, his picture forever on her bureau. An excellent widow-manqué can be found in Jane, one of the two spinstered Sawyer sisters in Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm , who lost her great love to the Civil War. Although Jane had “never left Riverboro in all the years that lay between and [had] grown into… [a] spare New England spinster… underneath was still the faint echo of that wild heartbeat of girlhood.” Her sister, in comparison, was hard, unyielding, and nasty. And occasionally a spinster character might redeem herself by marrying late, miraculously shedding her dusty paper chains. A great twentieth-century example is Miss Parthenia Ann Hawks of the musical Show Boat (1926), who’d lived “a barren spinster’s life” before her marriage to Cap’n Andy.

The corollary of the single woman who refused to bear healthy white children was her married contemporary who sought ways to abort unwanted children. During the mid-nineteenth century, in the decades just before the abortion outlaw, a common image in the American press was “the Aborting Matron,” a piggy, self-satisfied wife downing poison or else portrayed as demonically possessed.

The majority of applicants turned back at Ellis Island were unable to prove that they had waiting relatives. Either that, or they had physical problems (usually eye trouble) and/or mental disorders. Being female and single—and especially if there were no waiting relatives—was at times as incriminating as rheumy eyes. Many, many lone female travelers were sent back.

The most famous ghettoizing process was under way at the phone company. Telephone operator had been a respectable job, meaning a male job, until corporate expansion created several tiers of more challenging positions. By as early as 1902, the Bell Telephone System employed 37,000 female switchboard operators. Their rationale: Women had “more calming” voices and were “more patient.”

Читать дальше