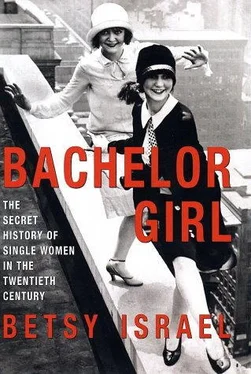

Betsy Israel

BACHELOR GIRL

The Secret History of Single Women in the Twentieth Century

Hayley Israel Doner,

greatest single girl I know

This book would not exist without the foresight, goodwill, and patience of two extraordinary people. My agent, Susan Ramer, has been with me through three proposals, five drafts, and an epic spell of writer’s fog. She has devoted so much time to this project, worked through so many of its problems, and been such a wonderful friend that I cannot thank her enough. Jennifer Hershey is the most thoughtful, good-natured, and enthusiastic editor I’ve ever worked with. She helped me to find a way through what seemed a great dark mass of material and never did she doubt it would take shape. Despite an enormous workload, she personally edited this book down to the tiniest detail. Maureen O’Brien, a terrific editor and good pal, saw Bachelor Girl through to its conclusion and ace publicist Jessica Miller worked tirelessly to get it read. I am indebted to my research assistant, Jeryl Brunner, the woman who can find anything, anywhere. Thanks, too, to Jeanine Barry, Carleen Woolley, and Ariana Calderon for their assistance and fact-finding. Donna Brodie at the Writer’s Room gave me much-needed early encouragement, and Amy Gross offered me the chance to write about single women, in Mirabella . Thanks, too, to all the friends, colleagues, and relatives who have listened and commented throughout. In particular I am grateful to my husband, Ezra Doner, and to Nan Friedman, Betsy Zeidman, Priscilla Mulvihill, Lorraine Rapp, Fleur and Sheldon Israel, the late Alex Greenfield, Sally Hines, and Dalma Heyn; to Teriananda, who took care of my household; and to Susannah Israel Marchese, who had an easy answer to my hardest question. My beloved Hayley and Timothy have been more tolerant and patient than any children should ever have to be. Finally, my inestimable thanks to the many women who so carefully and honestly described their lives as bachelor girls.

INTRODUCTION

I Think We’re Alone Now

Commands sent through highways and byways… drawing rooms, workshops, by hints and suggestions… lectures… the imploring letter… essays… sermons… as if a voice… din[s] in the ears of young women: Marry! Marry! For the unmarried woman fails at the end for which she was created.

—“THE WAY OF ALL WOMEN,”

HARPER’S , 1907

We all grow up with images of single life. For me, these were brightly colored fantasies that drew on TV heroines— That Girl Marlo Thomas, Avenger Emma Peel, Catwoman, the Mary-and-Rhoda duet—and a vision of how I’d look in the tight little blue suits of UN tour guides and stewardesses. A young woman plotting out a single life circa 2002 has a broader, more eccentric range of iconic singles to play with, each wearing her own unique single suit: Ally McBeal, cute, hallucinating miniskirted lawyer; Bridget Jones, “singleton,” who sees clearly the masochism inherent in both her single life and her own ill-fitting tiny skirts; and the Sex and the City foursome, who, like doctors or madams, discuss clinical aspects of sex, while dressed for sex, in restaurants.

More so than any other living arrangement, the single life is deeply influenced— haunted may be a better word—by cultural imagery. And the single woman herself has had a starring role in the mass imagination for many years. Admit it or not, most of us have our fixed ideas of single womanhood and at some point we all indulge in the familiar ritual of speculation: How did she end up that way? How can she stand it? And how might she correct what must be a dull, lonely, and potentially heartbreaking, meaning possibly childless, situation?

One hundred and fifty years ago, Sarah Grimké, tough “singleside” and “womanist,” wrote that marriage had ceased to be the “sine qua non of female existence.” In every decade since, many, many women have come to agree with her. And they have inspired more than the familiar ritual of pitying speculation and disdain. Single women seem forever to unnerve, anger, and unwittingly scare large swaths of the population, both female and male.

Writing from an academic viewpoint, historian Nina Auerbach notes, “Though the nature of the [single] threat shifts… the idea remains of contagion by values that are contrary to the best and proudest instincts of humanity.”

A woman writing in the New York Times some years back put it plainly: “There’s something about a woman standing by herself. People wonder what she wants.”

The media, in all its antique and more recognizable forms, has long served as the conduit for this stereotypical single imagery. Reporters, novelists, and filmmakers again and again have introduced the single icons of the moment by organizing them into special interest groups with neon nicknames: Spinsters! Working Girls! Flappers! Beatniks! Career Women! That’s the job, of course, to discover and explore newly evolving social phenomena. In the process, however, they’ve repeatedly turned the new single into a nasty cartoon or a caricature.

Most of the standard single icons have been portrayed as so depressing, so needy and unattractive, that for years women who even slightly matched the descriptions had a hard time in life. But gradually all variety of single types began to flourish within their own tiny worlds and eventually found that they might stake a claim in the larger one. And contrary to the melancholy depictions, the weepy confessionals, many audacious and self-supporting single women had a lot of fun along the way. They continue to. And so the press continues to cover them as well as what is still perceived as their “condition.”

My own young single life, and how it abruptly ended, makes a strong case study in the power of single imagery and the way our mass media distorts it. That particular ending also marks the beginning of this book.

SNAPSHOTS FROM A SINGLE LIFE

In 1986, I was twenty-seven, living alone, and working in publishing—a youthful life phase that I’d spent years trying to organize and had enjoyed, until the day I got up and heard the news. According to bulletins on the Today show, National Public Radio, and every local newscast, I had officially become a Single Woman. To summarize briefly what newscasters milked for half an hour: A study now infamous for its flaws had revealed an alarming decrease in marriage “prospects” among women anywhere in age between twenty-five and forty. If, like me, you’d “postponed matrimony” due to your career or your generational tendency to cohabit, you’d now confront the tragic reality of your birth cohort: There weren’t enough men and potential husbands for you and all of your friends.

It seemed ridiculous—a prespinster at twenty-seven? No hope of marrying at forty? Yet two researchers from Harvard and Yale were assuring me that my life and the lives of just about everyone I knew were now ruptured.

Before all this—as in the day before—I had been merely me: an attractive, short, nervous person who did well in jobs requiring “girls” with excitable temperaments. At the time I was a writer for several similar lifestyle magazines. On any given day I’d find myself celebrating the “flippy sandal,” then skipping my way through a list of topics that might include thighs, parental death, the penis, betrayal, the truth of bagels, and a story inevitably called “Abortion Rights Are Still with Us.”

I was smart, or as some ex-boyfriends liked to say, I really was in my own way very clever. For example, I had struggled against the single fates (“live at home” or “have five roommates”) and had won. I had a place. No matter that at first—and second—glance it seemed situated inside a tenement. It was “rent-stabilized,” a phrase that, for young New York women of the time, was a lot more exciting, filled with more possibility and the hint of adulthood, than “marry me.” The details—cabbagey, narrow hallways; spindly, crooked Dr. Seuss–like stairs—didn’t bother me. The point was to learn certain survival skills. How did you negotiate with landlords who conversed with your breasts? How to deal with the roaches my neighbor referred to as “BMW’s,” for “big mothers with wings”? And how to get past the grannies, the babushka ladies who hissed as a group when they saw me? Every day I ran an obstacle course—bugs, ladies, landlord—not stopping until I shoved open door #5 with my hip and stepped inside.

Читать дальше