It was a policy that required the investment of whatever resources Lorenzo could muster. As with every project, he was ambitious. Shortly after marrying off his young daughter Maddalena to the pope’s dissolute son, he had the bank lend the Curia 30,000 florins. This was stretching credit to the limit. He accepted alum instead of cash for arrears repayments on papal loans, though the Medici no longer held the monopoly on merchandising alum and had few outlets from which they could sell the mineral. Every diplomatic courier traveling from Florence to Rome starts to bring gifts for Pope Innocent. Apparently the pontiff loves to eat game. Then ply him with game. He loves wine. Here are eighteen flasks of finest Vernaccia. And beautiful fabrics. And the best artists. Anything that will make His Holiness happy. “The pope sleeps with Lorenzo il Magnifico ’s eyes,” commented a delegate from Ferrara. Until at last the seduction was complete. In 1489, the pope caved in, waived age restrictions, and made the thirteen-year-old Giovanni di Lorenzo de’ Medici a cardinal. Now he could accumulate even more benefices. “The greatest honor ever conferred upon our house,” Lorenzo announced. Cardinal Giovanni de’ Medici, later Pope Leo X, would keep the Medici fortunes alive after their expulsion from Florence in 1494 until their return in 1512.

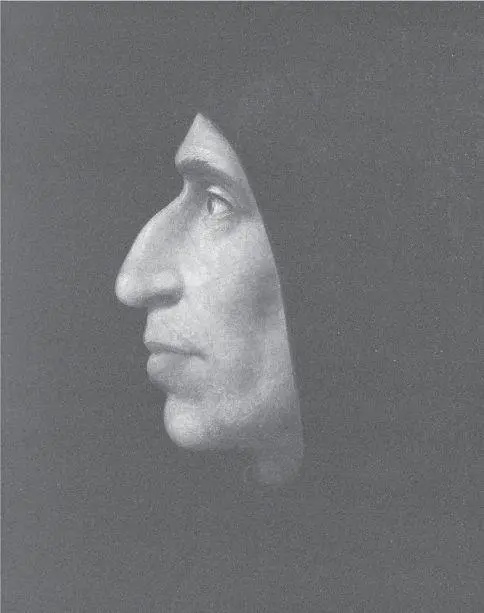

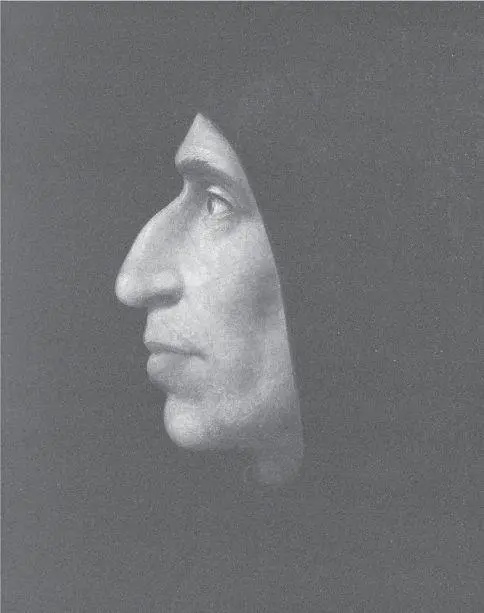

BUT THE CHURCH was not entirely rotten. While the Medici were seeking to consolidate the family’s temporal power through acquiring Church incomes, Il Magnifico ’s near-contemporary, Girolamo Savonarola, was climbing the ecclesiastical hierarchy in an entirely different spirit. Like the young Giovanni, Savonarola too would one day be offered a cardinal’s hat. And as with Giovanni, the appointment, or rather its offer, came as part of a bargain, an exchange, as though Church appointments were a recognized form of currency. With Giovanni, the honor constituted a payment for favors the Medici had already granted to pope and Church; in Savonarola’s case, the offer of the cardinalship was conditional on his granting a favor to Rome in the future: He must moderate his inflammatory preaching, he must get back into line, he must stop behaving as if he were in direct contact with God and holier than the official Church. Savonarola refused. “I don’t want any hats,” he replied to the pope, “nor mitres great or small; the only thing I want is what you gave your saints: death. A red hat, a hat of blood, that’s what I desire.”

Savonarola was the antithesis of Lorenzo and of the Medici and bankers in general. Here, at last, was a man who wouldn’t trade, a man who had no use for the art of exchange, who couldn’t be seduced. Yet, like Lorenzo, Savonarola was an artist, and in his own way a showman. His terrifying sermons of gloom and doom, of the need for radical spiritual renewal, transformed the Florence of Lorenzo’s and the Medici bank’s last years, setting Il Magnifico ’s ethos and achievements in sharp and twilit relief.

It had taken medieval Christianity a thousand years to produce the cautious revolution that was humanism, a movement eager to escape Christianity’s straitjacket, but careful never to renounce its principles. It took eclectic humanism only a hundred years to provoke the reaction that was Savonarola. But from the moment the secular began to creep into the sacred space, the bankers to gratify their vanity in altarpieces and tombs, the cardinals to collect their “discretionary” returns on deposits, the popes to mix up myth and prayer book — not to mention holy wars and commercial monopolies — Savonarola and, soon after him, Luther were figures in the making, men formed in opposition to a Church authority that was seen as corrupt; fundamentalists. Unlike the early Christians, they did not call their followers out of the world to a radically separate life. Instead, they demanded that official and powerful Christendom become truly Christian. The political consequences of such a transformation, should it ever take place, were enormous.

Born in Ferrara in 1452, called away from a career in medicine by a verse from Genesis —“Get thee out of thy country!”—Savonarola first preached in Florence between 1482 and 1487. “He introduced almost a new way of pronouncing God’s word, Apostolic, without dividing up the sermon, not proposing questions and answers, never singing, avoiding ornament and eloquence. His aim was just to expound something from the Old Testament and introduce the simplicity of the early church….”

Thus the comment of a contemporary. It was not, then, a return to medieval Christian preaching. The negatives in this description tell us that. There would be no old-style scholastic caviling. But neither would there be pretty quotations from classical authors, nor any reference to authorities outside the word of God. In a society buzzing with too many ideas, a Church cluttered with pricey secular bric-a-brac, Savonarola strips his Christianity down to the bare scriptures, the naked crucifix. “I sense a light within me,” he says. It is Christ, the light of the world. But not, as Ficino would have it, Plato’s light, or Proclus’s, or that of some Orphic hymn. “Oh priests, oh prelates of the Church of Christ,” cries Savonarola, “leave your benefices, which you cannot justly hold, leave your pomp, your splendid feasts and banquets.” He might have been preaching directly to Giovanni de’ Medici. Lorenzo also warned his son not to be corrupted by that “pit of iniquity” that was Rome. But there was no question of abandoning the benefices. Why else did one go into the Church?

The contrast alerts us to a condition essential to the development of international banks of the Medici variety: a certain laxity in the application of religious law, or, better still, a complete separation of church and state. In short, there is an affinity between money and eclecticism. “No man can serve two masters,” says Jesus. But money can serve any number. It is no respecter of principles. Broken up into discreet and neutral units, value flows into any cup, a shower of gold into any coffer, be it in Constantinople, Rome, or Jerusalem. The alum merchant trades with the Turk. The silk manufacturer is happy to sell provocative clothes to the pretty ladies of Florence. The idealist, whether Christian or Muslim, Communist or No-Global, must always be suspicious of money and banking. But the idealist is not to be confused with the ideas man. Quite the contrary. Admirably flexible, the humanist thinkers with their eclectic reading were notorious for finding authorities to justify whatever form of government best suited their paymasters. In 1471, Bartolomeo dedicated his treatise, “On the Prince,” to Federico Gonzaga. In 1475, the same text reappeared as “On the Citizen,” dedicated to Lorenzo de’ Medici. In the same period, depending upon which patrons were paying him, Francesco Patrizi wrote “On Republican Education” and then “On the Kingdom and Education of Kings.” Both systems were best. Money has a way of being right. Only popular government by the poor is unforgivable.

Savonarola, as portrayed by Fra Bartolomeo. The austere lines and sharp contrasts underline the man’s unswerving devotion and refusal to compromise. Finally, the Medici had met someone who could not be bought .

Spiritual renewal can only come through poverty, Savonarola preached, through an end to the clergy’s collusion with wealth and power. His would not be a church that worked with banks. Largely ignored, the monk left Florence in 1487. Meanwhile, the great political upheavals of his career behind him, Lorenzo was writing poetry again: cycles of love poems, dense with labored references to classical myth but lightened by marvelous landscape description. Busy with his verses, Il Magnifico ignored a proposal from Lorenzo Spinelli, the new director in Lyon, to revive the Medici bank’s old holding structure. Lorenzo himself was one of the bank’s main debtors now, one of the political leaders who would never repay. In 1488, a ban on public festivities in Florence, something that had been in force since the Pazzi conspiracy ten years ago, was finally lifted. Is it a coincidence that Lorenzo’s wife, Clarice, had succumbed to tuberculosis that same summer? Lorenzo was away at the thermal baths when she died. He wrote no poem for her. But for the first celebration of Carnival after a decade’s break, he produced some new Carnival songs, and some moving lyrics about youth. The loves of Bacchus and Ariadne are evoked to remind the adolescents of Florence to seize the day:

Читать дальше