Having “accumulated quite a bit on his conscience,” Vespasiano tells us, “as most men do who govern states and want to be ahead of the rest,” Cosimo consulted his bank’s client, Pope Eugenius, conveniently present in Florence (hence more or less under Cosimo’s protection) as to how God might “have mercy on him, and preserve him in the enjoyment of his temporal goods.” This was shortly after his return from exile.

Spend 10,000 florins restoring the Monastery of San Marco, Eugenius replied. It was the kind of capital required to set up a bank.

The monastery, however — a large, rambling, and crumbling structure within two minutes’ walk of both the duomo and Cosimo’s home — was presently run by a bunch of second-rate monks of the Silvestrine order reported as living “without poverty and without chastity.” Unforgivable. I’ll spend the money if you get rid of the Silvestrines and replace them with the Dominicans, Cosimo said. Those severe Dominicans! Only the prayers of men whose very identity was grounded in poverty and purity would be of use to a banker with an illegitimate child.

This was 1436, the year Pope Eugenius reconsecrated the duomo upon the completion, after more than fifteen years’ work, of Brunelleschi’s huge dome. With a diameter of 138 feet, the dome was the most considerable feat of architectural engineering for many hundreds of years. Its red tiles rose even higher than the white marble of Giotto’s slender ornamental tower beside the cathedral’s main entrance, and the two together completely dominated the skyline of the town in yet another ambiguous combination of local civic pride and devotion to faith. The Florentines, in fact, had for years been anxious that the dome would collapse, thereby inviting the ridicule rather than admiration of their neighbors.

On the occasion of the consecration, Cosimo bargained publicly with Eugenius to get an increase in the indulgence that the Church was handing out to all those who attended the ceremony. The pope gave way: ten years off purgatory instead of six. It cost no one anything and brought both banker and religious leader great popularity. On the matter of San Marco, the pope again proved flexible. The Silvestrines were evicted. The rigid Dominicans were moved in from Fiesole. Their leader at the time was Antonino, later Archbishop Antonino, a priest with a streak of fundamentalism about him. What would our Saint Dominic think, he wrote after the expensive renovation was complete, if he saw the houses and cells of his order “enlarged, vaulted, raised to the sky and most frivolously adorned with superfluous sculptures and paintings”?

But this fundamentalism was indeed only a streak — only a would-be severity, if you like — otherwise the priest could hardly have worked together with the banker for as long as he did. For the story of Cosimo’s relationship with Antonino, who oversaw the lavish San Marco renovation project and then became head of the Florentine church for most of Cosimo’s period of power, is the story of the Church’s uneasy accommodation with patronage of dubious origin. “True charity should be anonymous,” Giovanni Dominici, militant leader of the Dominican order, had insisted. “Take heed,” Jesus says, “that ye do not your alms before men, to be seen of them; otherwise ye have no reward of your Father which is in heaven.” The position is clear: no earthly honor through Christian patronage. But Antonino and Cosimo were both sufficiently intelligent to preserve those blind spots that allow for some useful exchange between metaphysics and money: in the ambiguous territory of art. In return for his cash, the banker would be allowed to display his piety and power. And superior aesthetic taste. The Church would pretend that all this beauty was exclusively for the glory of God, as it readily pretended that the building of the duomo ’s cupola had nothing to do with Brunelleschi’s megalomania. Without such dishonesty, the world would be a duller place.

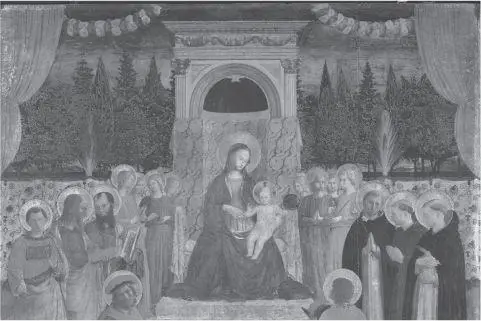

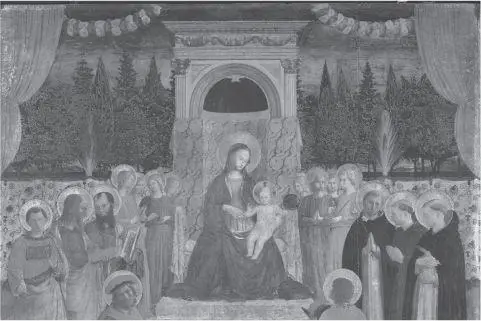

Michelozzo, more than ever Cosimo’s personal friend after sharing his period of exile, was the architect. The monks’ cells would be suitably austere. The library, with its rows of slim columns supporting clean white vaults, was a miracle of grace and light. Cosimo donated the books. Many were copied specifically for the purpose. Many were beautifully illuminated. The main artist in the project was Fra Angelico, otherwise known as Beato Angelico, a man who wept as he painted the crucifixions in all the novices’ cells. Quarrel with that if you will. Antonino insisted on crucifixions, especially for novices. The true purpose of art is to allow the Christian to contemplate Christ’s agony in every awful detail. But at the top of the stairs leading to those cold cells, Angelico’s Annunciation presents two sublimely feminine figures generously dressed as if by Florence’s best tailors. And in the church below, the monastery’s main altarpiece, The Coronation of the Virgin , shows just how far Cosimo has come since the tomb of Giovanni XXIII.

Holding her unexpected child, the Virgin sits crowned with banker’s gold in a strangely artificial space, as if her throne were on a stage, but open to trees behind. It was the kind of scene the city’s confraternities liked to set up for their celebrations, funded of course by benefactors such as the Medici. Aside from San Marco and San Domenico (patron saints of the monastery and of its newly incumbent order), the figures grouped around the Holy Mother are all Medici name-saints: San Lorenzo, for Cosimo’s brother, who had recently died; San Giovanni and San Pietro for Cosimo’s sons. Kneeling at the front of the picture, in the finest crimson gowns of the Florentine well-to-do, are San Cosma and San Damiano. Cosma on the left, wearing the same red cap that Cosimo prefers, turns the most doleful and supplicating face to the viewer, the Florentine congregation. Apparently he mediates between the people and the Divine, as Cosimo himself had done the day he got the pope to hand out ten years’ worth of indulgences instead of six. Damiano instead has his back to us and seems to hold the Virgin’s eyes.

In later years, other managers of the Medici bank — Francesco Sassetti, Tommaso Portinari, Giovanni Tornabuoni — would have themselves introduced directly into biblical scenes. Solemn in senatorial Roman robes as they gazed on the holy mysteries, they showed that at least in art there need be no contradiction between classical republic and city of God, between banker and beatitude. Cosimo had more tact. He appeared only by proxy, in his patron saint. Or saints. For he never forgot to include brother Damiano, perhaps half hidden by Cosma’s body, turned toward the Virgin, or the crucifixion, as if half of the living Cosimo were already beyond this earth, in heaven, with his dead twin brother. No doubt this generated a certain pathos. “Cosimo was always in a hurry to have his commissions finished,” said Vespasiano da Bisticci, “because with his gout he feared he would die young.” He was in a hurry to finish San Marco, in a hurry to finish the huge renovation of his local church, San Lorenzo, then the beautiful Badia di Fiesole, the Santissima Annunziata, and many others as the years and decades flew by, including the restoration of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Ever in a hurry, he grew old fearing he would die young. Perhaps it was this that made him such a master of the ad hoc.

Fra Angelico’s Coronation of the Virgin, one of the many paintings commissioned by Cosimo de’ Medici when he undertook the restoration of the monastery of San Marco. Six of the eight saints in attendance are Medici name saints, with St. Cosma turning to face the congregation in the foreground to the left, balanced by San Damiano on the right. Around the edge of the luxurious carpet run red balls on a golden field, the motif of the Medici family. The sacred space thus becomes more comfortable, for the rich .

Читать дальше