Or is it? Clearly, Rome has a special status. Not just a despot, but God’s vicar on earth, the pope, if seriously threatened, can order an interdiction, as he did in Florence in the fourteenth century. Then the priests won’t perform your marriage ceremony or give you last rites or bury your dead. Without ritual, the world comes to a standstill. Rome, aside from moments of Angevin delirium, or internal republican revolt, is untouchable.

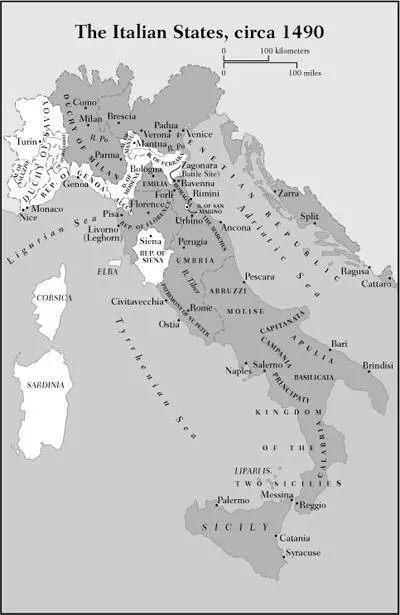

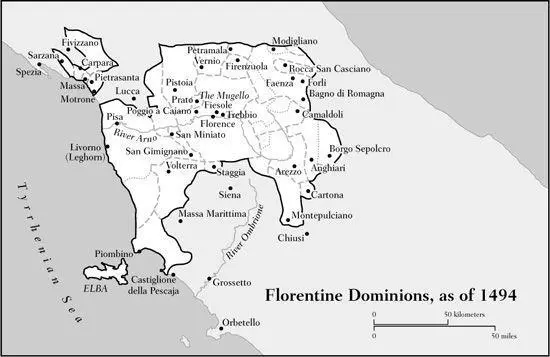

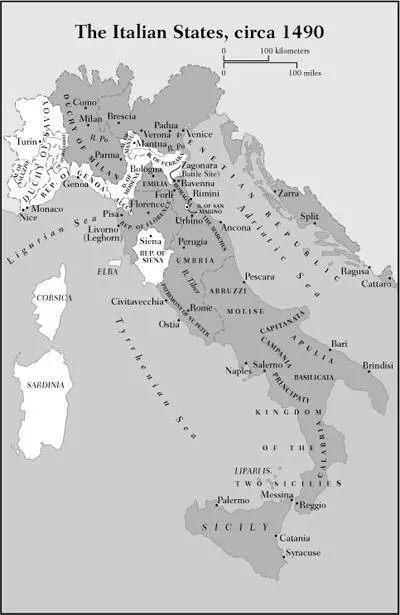

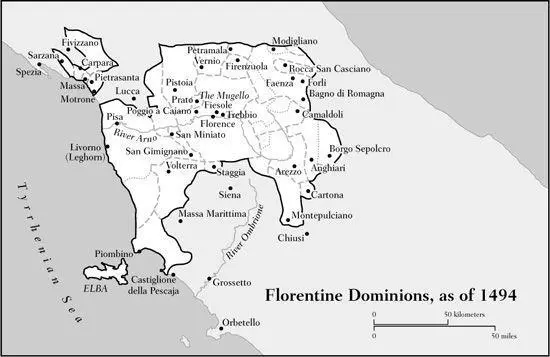

Nor, aside from brief interludes of Visconti aberration, do Milan, Venice, and Florence really believe they could conquer and absorb one of the others, since that would provoke an unstoppable alliance against them. Begun with great energy and straightforward goals, these wars immediately complicate. The combatants suffer a loss of faith. Armies get bogged down and confused. Winter comes. People are tired and cold. Eventually, they make peace and the prewar situation is reestablished, give or take a citadel or two. Even where a large city is captured, it is rarely integrated into the conquerors’ territory. The Pisans, for example, conquered in 1406, do not enjoy the benefits of Florentine citizenship. Pisa is a subject town, a cow to milk, an outlet to the sea. Hence the Pisans are determined to rebel the moment circumstances are favorable. Gobbled up, the fruit is never properly swallowed. The game can start again, and always does.

Looking back on it all from the vantage point of the 1520s, Machiavelli was disgusted: “One cannot affirm it to be peace where principalities frequently attack one another with arms; yet they cannot be called wars in which men are not killed, cities are not sacked, principalities are not destroyed, for these wars came to such weakness that they were begun without fear, carried on without danger, and ended without loss.” Without much loss of life and territory, that is. But not without the loss of huge sums of money. This is where the Medici came in. Even when it most resembles a sport, even when it is most futile, war is always cruelly expensive. And where war is never conclusive, a constant supply of money becomes absolutely essential.

BUT HOW WAS it that so few people were killed? Machiavelli puts it down to the tendency of the states involved to use mercenary troops led by professional condottieri . By-product of a decadent feudalism, the condottiere is a warlord with a private army. Many signori of small towns and citadels find that renting out themselves and their soldiers is the only way to stay solvent and independent. A condottiere without a small town has no scruples about acquiring one. An army needs a base. For the big players who hire the mercenaries, there is the advantage that few of their own citizens need risk death when war is declared. People can get on with business as usual. Also, there is no danger that some parvenu commander from their own ranks will attempt a coup. The last thing a state with a fragile government needs is some home-bred, charismatic military leader.

The Italians were more advanced in the art of warfare than the other states of Europe and as a result their condottieri were much in demand in other countries. These men deposited their earnings with their preferred Italian bank — in Bruges or Geneva — and had the money sent home. However, since the mercenary soldier had nothing to gain from putting himself out of work, there was the drawback that the condottieri , particularly in Italy where they all knew each other, were notoriously disinclined to finish a job. “Enemies were despoiled, but then neither detained nor killed,” complains Machiavelli, “so that the conquered only put off attacking the conqueror again until such time as whoever was leading them could refurbish them with arms and horses.” Which meant spending a great deal of money, of course. Not to mention the fact that even when they lost, mercenary troops still demanded their wages. When they won, on the other hand, they had a habit of taking all the booty for themselves. In fact, in a certain sense, when you used condottieri , even when you won, you lost. In 1427, having spent the vast sum of 3 million florins in five years of war, Florence was plunged into an economic crisis that wonderfully clarified the political situation in the town. There was a dominant faction, headed by the Albizzi family, desperate to raise new taxes, and there was the immensely wealthy Medici family who, without actually proposing anything, had become a nucleus for discontent.

A state’s ability to wage war is largely determined by its people’s willingness to pay their taxes. That is a truism. “What was this wealth for?” Sultan Mehmet II would inquire of Constantinople’s first minister after the great city finally fell in 1453. House after ransacked house yielded treasures withheld from the taxman. “What good are they now?” The first minister hung his head. “No price is too high for our liberty,” Cosimo de’ Medici liked to say; and he may have meant it, but when a wealth tax was imposed, he gave orders to the bank’s directors to create fake accounts to limit the damage. “Most of the time tax returns are of no use at all for statistical purposes,” regrets the historian Raymond de Roover.

Shortly after a disastrous Florentine defeat at the hands of Milanese forces at Zagonara in 1424, an extraordinary sequence of frescoes began to appear on the walls of a chapel in the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine on the south side of the Arno River. Masaccio’s The Tribute Money shows Jesus and his disciples being challenged by the tax collector as they enter a town beside a lake. Jesus makes a commanding gesture. In response, the fisherman, Peter, is shown at the left of the picture extracting a gold coin from the mouth of a fish that has generously given itself up at the water’s edge; over to the right, the same disciple is already paying the coin to the taxman. Even Christ pays his taxes, the picture says. Even the Church. Pay up, everybody! On another wall the early Christians are shown sharing out their wealth among themselves in community spirit. But someone is lying face down in the dirt. Ananias didn’t tell the truth about the price he got when he sold his property to pool the money with that of his fellow believers. He held a little back for himself. God struck him dead. The rich silk merchant Felice Brancacci, who commissioned this most beautiful of chapels, was himself a major tax evader. Like Cosimo, he held back a great deal. But then not all of us find gold coins in the mouths of fish. Being struck dead from on high is also rare.

I can imagine no better introduction to Italy and Italian politics than Machiavelli’s Florentine Histories , inaccurate and biased as much of the book may be. It is the mindset that counts. To read a few pages describing how tortuous maneuverings were cloaked in noble rhetoric is to be amused. The idea of the spin doctor is not new, it seems. Of every diplomatic policy, the fifteenth-century Italian considered its utile , the hard results, and its riputazione , how it might be presented in the best light. “Then the Pope”—or the doge or the duke of Milan, says Machiavelli—“filled all Italy with letters,” to explain why he had changed sides, perhaps, or why he couldn’t help an ally in difficulty, or that he was fighting on behalf of liberty. It’s a common refrain in Florentine Histories . Whenever somebody “fills all Italy with letters,” you can be sure they are lying.

Читать дальше