The Italian agricultural propaganda newspaper La Domenica dell’Agricoltore asserted that the Integral Method was the method best suited for the new early wheats developed by Italian geneticists, for their demands were fully satisfied by the continuous and vigilant care taken by adherents of that method. [7]Indeed, such care was the method’s distinctive feature, and it promised to convert wheat extensive cultivation, with its labor peak during harvest, into an intensive activity that nursed the wheat plant at every stage of development. Seeds were to be carefully placed in parallel rows spaced widely enough for peasants to move between them while performing the year-round activities of weeding, fertilizing, and draining. For Pequito Rebelo there was no doubt that the lined fields of the Integral Method would transform extensive properties into gardens demanding the permanent presence of industrious and attentive peasants.

Strong ideas about the national soil were central to Integralists’ visions of the organic nation. António Sardinha (1887–1925), the most famous of the Integralist intellectuals, celebrated sedentary Lusitan tribes that inhabited the Portuguese territory in pre-Roman times and allegedly constituted the core of the Portuguese race in spite of many subsequent “horrendous exotic alluviums.” [8]Sardinha warned against a republican race, produced by the contamination from Jewish and Black elements, responsible for the introduction in the country of a liberal abstract ideology completely detached from national traditions. [9]He exulted instead over a mythical “Atlantic Man” who year after year cultivated the same soil in which his ancestors were buried. For Integralists, the cult of the ancestors and the tilling of the land were deeply connected in a too-familiar mix of blood and land that they adapted directly from Maurice Barrès, the main inspirer of French radical reactionaries and of many fascist movements across Europe. By 1915, Sardinha had published a volume of collected poems titled The Epics of the Plain : Poems of Land and Blood . [10]

Sardinha’s telluric journey led him to the plains of Alentejo. For those familiar with the poet’s biography this was a natural choice, for his home town, Monforte, is located in Alentejo. The local abundance of megalithic funerary monuments from the Neolithic and Bronze Age materialized in the landscape the cult of the ancestors and surely contributed to Sardinha’s sense of communion with “the honorable farmers that have at all times stared at the horizon that I now stare at.” [11]However, for a reader informed about the political economy of Alentejo, with its large estates and their seasonal workforce, the region was a very unlikely setting for national epics. [12]Not only were the vast majority of properties not in peasants’ hands; there also was a consensus about the negative social effects of the divorce between land ownership and agricultural workers. Since the end of the eighteenth century, popular narratives had insisted on the lawlessness of the scarcely populated region and had attributed the extreme levels of burglary and vagrancy, which were among the highest in the country, to weak bonds between the population and the land. [13]Adding to this grim vision, extensive tracts of land, moors, and heaths were kept uncultivated until the first decades of the twentieth century, which justified the metaphor of Alentejo as a sort of Portuguese Wild West. [14]

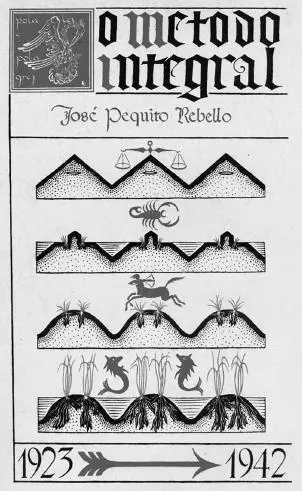

Figure 2.1 The cover of José Pequito Rebelo’s book O Método Integral, 1923–1942 (Gama, 1942).

Integralists had thus no easy task in making Alentejo’s soil the source of virtues of the organic nation. Indeed, most of the myths put in circulation by Portuguese intellectuals at the turn of the century had the northern regions of the country as the birthplace of the Portuguese nation, identifying the south, and Alentejo in particular, with bad influences of Jewish and Arab origin. [15]But although the political trajectories of the members of Luso-Integralism are usually described in terms of an aesthetic option for literary traditionalism that evolved into strong counter-revolutionary nationalism, they employed tools other than just poetry to make the southern lands produce morally upright Portuguese. And here we again stumble into Pequito Rebelo, who was occupied less with poetry than with the invention of new agricultural machinery for the application of his Integral Method for grain production, urging intensive care of each individual plant all year round. [16]

The much-criticized extensive cultivation of cereals over large areas in Alentejo, with its masses of migrant workers hired only for short periods of time, was to be replaced by well-kept “wheat gardens” producing proud farmers who would constitute the backbone of the nation. For Pequito Rebelo, it did not matter that Alentejo shared with other Mediterranean regions, such as the Italian Mezzogiorno, many of the geographical characteristics that made wheat cultivation a taxing activity. Transforming defects into virtues, Pequito Rebelo saw in the use of “refined techniques” to overcome poor natural conditions the possibility to convert extensive cereals cultivation into a “sort of horticulture” that would have “a happy influence on the social type.” [17]The qualities of the national soil were to be measured not only by its productivity but also by its ability to “reveal the virtues of the race…. If cereal cultivation is complex, with plants regularly ordered, continual weeding interventions at each development stage and defense them against natural adversities; if all this is done using perfected tools that praise the inventive qualities of the farmer; then it must influence the social type for the better.” [18]In short, the challenges of Alentejo’s landscape made it possible to sustain a virtuous national community.

A few years before his visit to Italy, Pequito Rebelo had published Farmer’s Primer (1922), in which he had used the ordered fields of the Integral Method as a simple metaphor to help rural people to understand the new social order advocated by Luso-Integralists: “The counter-revolution, the reaction , is the same thing as taking over a poorly governed homestead and giving it order and good habits.” [19]In 1928, already two years into dictatorial rule, in a speech at the students union of the University of Coimbra (the first supplier of high-ranking bureaucrats to the state apparatus), Pequito Rebelo had in mind something more than just metaphors for simple-minded farmers. On that occasion, he argued that applying the Integral Method meant producing the Integral Nation. According to Pequito Rebelo’s political agenda, hard-working farmers and peasants organized in rural syndicates denied the individualistic theories of liberalism and formed the basis of a nation built on authentic corporations and not on artificial class organizations. Therefore, Pequito Rebelo urged “our dictatorial government” to “follow the example of our sister dictatorships and show its agrophile intentions as the fundamental idea of administration.” [20]More emphatically, “the political renaissance of the Latin people goes hand in hand with the apotheosis of Ceres. One just has to watch Mussolini calling himself the agricultural condottiere , designing and commanding the battaglia del grano , and asserting that bisogna ruralizare l’Italia , Italy must be ruralized.” [21]Ruralization was thus to become one of the main features of the recently inaugurated dictatorial regime.

The Portuguese Wheat Campaign: Chemical Fertilizers and Large Estates

Читать дальше