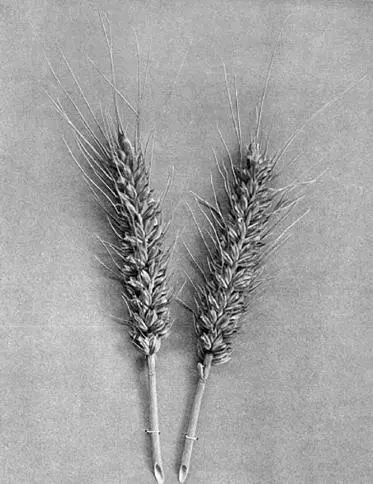

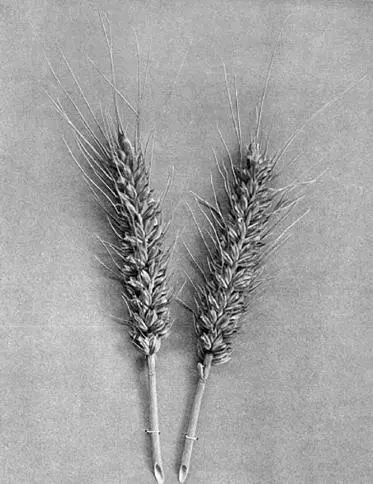

The Ardito hybrid was to assume the burden of saving Strampelli’s reputation. To produce that strain, the geneticist employed exotic varieties from the collection of wheats from around the world that he had been accumulating in his institution. According to Sergio Salvi’s reconstruction of the process, Strampelli corresponded with the main centers of wheat breeding in the world (among them Wageningen, St. Petersburg, and the Vilmorin company). [43]This was a central feature of any ambitious hybridization program: to have at its disposal a large variety of plants from different origins, ready to be combined in the most productive way. [44]Instead of operating as the old Botanic Gardens did, acclimatizing entire trees and plants, the geneticist at the Rieti Experiment Station combined organisms that, taken in isolation, presented no obvious benefit. No other case is more convincing than the development of Ardito , which resulted from hybridization of the already highly productive hybrid of Rieti and Wilhelmina Tarve with the Japanese strain Akagomuchi . The Japanese variety had no value when standing alone in a field, but its precocity was a precious resource to incorporate into Ardito , which would mature fifteen to twenty days earlier than common varieties. Not only could the terrain be used for a second crop; equally important, advancing the harvest season minimized the effects of drought. Also, earlier harvests meant less exposure of peasants to malaria, a crucial issue for the unreclaimed lands of southern Italy.

And this was not all. Crucially, the Akagomuchi strain, with its small and thick stems, also conferred on Ardito great resistance to lodging, allowing generous use of chemical fertilizers. Ardito would thus become the best friend of the big chemical conglomerate formed by fascist developmentist economic policy. Strampelli talked of productivities that might reach 64 quintals per hectare (94 bushels per acre), more than ten times those achieved with common varieties. This combination of dwarf Japanese wheats with fertilizers immediately evokes the Norman Borlaug varieties that revolutionized grain production in India and Mexico in the 1960s, thus confirming Jonathan Harwood’s suggestion that we should talk of a first Green Revolution in the early decades of the twentieth century. [45]

Figure 1.6 Strampelli’s Ardito wheat, 1932.

(Strampelli, “I Miei Lavori”)

Strampelli released his new variety in 1920. But only with the launching of the fascist “Battle of Wheat” were the new elite races to find massive diffusion in Italy. In 1925, three years into fascist rule, Strampelli’s wheats occupied no more than 3 percent of the cultivated grain area of Italy. That would climb to 30 percent in 1932 and would exceed 50 percent in 1940. [46]In the fertile areas of the Po Valley in northern Italy, Strampelli’s hybrids monopolized the entire market. In the highly productive province of Ferrara, about 90 percent of the total grain acreage was planted with Strampelli’s seeds. [47]Not only did grain production skyrocket with the massive use of fertilizers, more than doubling wheat productivity in Ferrara, but the early character of grains such as Ardito offered the possibility of freeing the land for production of rice, tobacco, or linen, further contributing to the autarky policies of the fascist regime. [48]

If such figures confirm the verdict that the Battle of Wheat benefited primarily the more modern sectors of Italian agriculture, such as the areas of capitalist agriculture of the Po Valley, the effects were no less dramatic in the south, where the legendarily backward large estates dominated. [49]In 1938 the newspaper Agricoltura Fascista claimed that no less than 65 percent of the wheat fields of the south were cultivated with the new hybrids. [50]In Apulia, Senatore Cappelli was the strain of hard wheat responsible for the diffusion of Strampelli’s name through the fields. Between 1937 and 1938 there was a fierce debate among Italian wheat experts on where in the southern regions it was advisable to use the new high-yield soft wheats, and which areas should stick to the more reliable but less productive hard wheats, which were better adapted to the arid conditions. [51]But if the main results in northern regions were due to intensify grain production, in the south the “Battle of Wheat” was fought by greatly expanding wheat acreage into previously uncultivated areas occupied by grasslands and woods. While in northern and central Italy the area dedicated to wheat cultivation increased by only 5 percent between the beginning of the 1920s and the end of the 1930s, corresponding to an extra 116,000 hectares (290,000 acres), in the south the wheat fields were enlarged by about 265,000 hectares (662,500 acres), or 13 percent. [52]The immediate result of such expansion was not only an increment in wheat production but also a true disaster for animal husbandry, a major activity in the economy of southern Italy: between 1926 and 1929 the number of sheep and goats declined by between 4 million and 5 million. [53]

Such major effects on the Italian landscape were, of course, results of the gigantic act of propaganda of the Battle of Wheat. This was not just empty fascist rhetoric, for we are dealing here with a concrete increased infrastructural presence of the state in the territory. In fact, one of the initiatives promoted by the campaign was the formation of associations and consortia of farmers financed by the state with the aim of producing and distributing new high-yield seeds. [54]By 1930, seven seed centers (in Sardinia, Sicily, Calabria, Puglia, Basilicata, Lazio, and Tuscany) had been set up by farmers’ syndicates. The connection with Strampelli’s Institute of Genetics couldn’t be more intimate: its local experiment stations, such as those in Foggia and on the island of Sardinia, were responsible for forming the local consortia. Selected farmers in each region were trusted with the task of reproducing the elite seeds under controlled conditions by the experiment station, after which the consortia would sell the certified seeds to farmers at controlled prices. Small landholders were given, gratis, a small quantity of selected seed under the obligation of cultivating it and getting rid of an equivalent amount of traditional landraces or, as an alternative, were paid back the difference between the price of new strains and traditional ones. From 1926 to 1930 about 100,000 quintals of selected seed were handed to small farmers through this scheme of “seed exchange,” which aimed at a large-scale replacement of traditional varieties in Italian fields by the breeders’ technoscientific artifacts. [55]

The targeting of small landholders didn’t change the fact that large farmers were the main beneficiaries of the system: they controlled the consortia, got extra income from reproducing selected seeds because they had been selected as model farmers, and had more capital with which to buy the fertilizers that revealed the good qualities of the new strains. Only if small farmers were given Strampelli’s varieties at no cost could they be persuaded to use the new seeds. To convince them, the campaign funded, in addition, no less than 30,000 demonstration fields scattered through every wheat-producing village in the country. [56]These were small properties of no more than a hectare (2½ acres), always close to public roads, for which small farmers received free seed and fertilizers for a couple of years. At key moments—seeding, fertilization, and harvest—the consortia invited the rest of the local farmers to observe the results, which were also publicized in the local press and by local priests.

Читать дальше