No historian of fascist Italy ignores the much-publicized images of Mussolini threshing wheat while stripped to the waist and wearing futuristic goggles, simultaneously playing two of his best-known roles: the First Peasant of Italy and the Flying Duce. [6]In 1926, the first summer of the Battle of Wheat, Illustrazione Italiana published photos of the dictator amid tractors, harvesting wheat, or driving a mechanical sowing machine. The appearance in the mass media of images of the leader among agriculture workers would become an annual ritual of fascist Italy that would culminate in the 1938 documentary film Il Duce inizia la trebbiatura del grana nell’Agro Pontino ( The Duce Launches the Threshing in the Pontine Ager ). After the narrator reminded the audience of the 200,000 quintals of wheat produced that year in the recently reclaimed Pontine Marshes, the camera tracked Mussolini, who was said to have threshed about 11 quintals in just an hour. [7]In typical fascist manner, this cult of the leader was combined with the organization of mass events, such as demonstrations of wheat threshing in Rome’s central squares and the grandiose national exhibitions of grain held in 1927 and 1932. It is no exaggeration to state that the Battle of Wheat was the first mass propaganda act of Mussolini’s regime, mobilizing film directors, photographers, radio speakers, journalists, and even priests to spread the new gospel. [8]

In spite of the consensus around the importance of the Battle of Wheat for the regime’s imagery, the general historiographical verdict about its effects tends to assume a negative tone. [9]The campaign is perceived as the price paid by the National Fascist Party to guarantee support from backward southern landowners who would not survive without generous state subsidies in the form of high duties on foreign cereals. [10]Historians have also identified the modern capitalist landowners of the northern fertile areas of the Po Valley as major beneficiaries of the regime of wheat autarky, making big profits on the backs of underpaid wage laborers. Although the regime promised to defend small landowners and sharecroppers as the backbone of the national community, this middle stratum of Italian peasantry migrated in increasing numbers to urban centers during the fascist years. The campaign was also funded by consumers paying higher prices for bread, for Italian wheat was always more expensive than North American or Argentinean grain sold in international markets. This negatively affected not only the domestic budget of city dwellers, particularly industrial workers, but also that of small farmers inhabiting Italian mountain regions where meager grain production, insufficient for local consumption, required them to buy their bread at climbing prices. The Battle of Wheat is also held responsible for an excessive obsession with wheat production that undermined the previous diversity of Italian agriculture, penalizing fruit, vegetable, and wine production and contributing to accelerate soil erosion through the cultivation of poor thin soils. Ten years after the launching of the Battle of Wheat, Italy produced 40 percent more wheat but had increased its food deficit in other items, especially meat. To summarize, the “mission accomplished” banner heralded by Mussolini in 1933, when productivity rose above 15 quintals per hectare, is seen as another act of propaganda by a regime exaggerating its feats while hiding the many problems caused by its policies.

Figure 1.1 Armando Bruni, “Mussolini threshing wheat at the Agro Pontino” (1935).

(Fondo Armando Bruni / Rcs Archive)

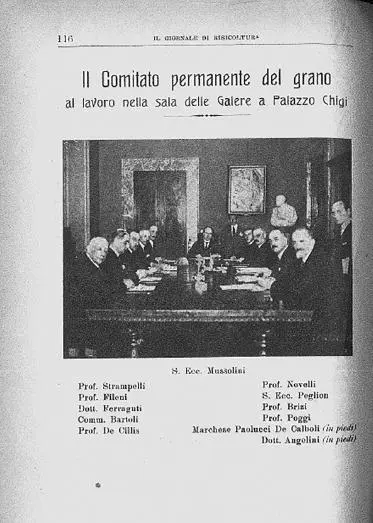

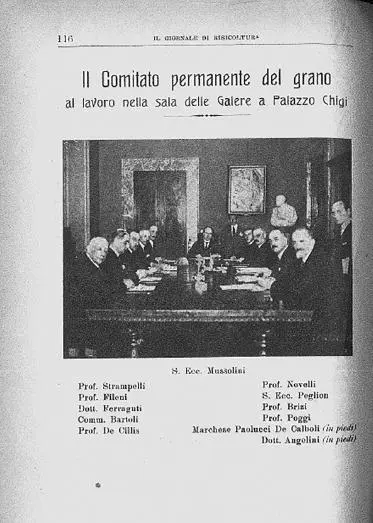

My intention here is not to dispute this historiographical consensus over the many failures of the Battle of Wheat. I am interested, instead, in emphasizing how the campaign constituted one of the first materializations of the fascist regime, with scientists, especially geneticists, playing a major role in the process of building the New State. We can get a first hint of this interaction between science and politics just by looking at the constitution of the Permanent Wheat Committee founded in 1925 to command the battle. [11]The Duce himself headed the new organism formed from a mix of high-ranking state officials (Minister of the National Economy Giuseppe Belluzo, General Director of the Agricultural Services Alessandro Brizi), renowned agricultural scientists (Mario Ferraguti, Tito Poggi, Enrico Fileni, Novello Novelli, Emanuele De Cillis, Nazareno Strampelli), and representatives of farmers syndicates (Antonino Battoli, vice-president of FISA), to be joined later by leaders of fascist peasant unions (Luigi Razza). [12]The meetings of the committee thus were a combination of charismatic leadership, state apparatus, corporatist organizations, and science. [13]

Figure 1.2 The Permanent Committee of the Wheat Campaign, 1925. Nazareno Strampelli is seated immediately to the right of Mussolini.

(Il Giornale di Risicoltura 15, no. 8 (1925): 116)

Other than by increasing tariffs on foreign grains, how was Italy to increase its wheat production? On July 4, 1925, in a speech that inaugurated the work of the Permanent Wheat Committee, Mussolini used emphatic rhetoric to give first priority to the distribution of high-yield seeds to Italian farmers. Other measures, such as intensive use of fertilizers and better preparation of the soil, were directly dependent of the success of that first task. Only by employing wheat varieties with high-yield potential could one capitalize the Italian fields with fertilizers and machinery. It would not make much sense to launch powerful para-state agencies such as S. A. Fertilizzanti Naturali Italia (SAFNI), founded in 1927 to promote the modernization of the chemical industry, if the seeds employed by farmers could not profit from the use of phosphates and nitrates. [14]The Battle of Wheat was not designed only to have a profound influence on the rural world; it was also supposed to boost the output of the chemical industry—a requisite for any policy of autarky as perceived by such first-rank leaders of the regime as the engineer Giuseppe Belluzzo, Minister of the National Economy from 1925 to 1928. [15]

It is, then, no surprise to find that the committee included Emanuele De Cillis and Enrico Fineli. Professor De Cillis, of the Royal Institute of Agriculture of Portici (Naples), the foremost expert on methods of wheat cultivation in the southern regions of Italy, dedicated his efforts to coping with the difficult conditions of the arid regions of Apulia, Basilicata, and Calabria. [16]Fineli, a no less important figure, was head of the extended network of Cattedre ambulanti d’agricoltura, which consisted of about 500 local chairs of agriculture in charge of introducing Italian farmers to the latest developments in husbandry. [17]Each local chair was made responsible for a Commission for Granary Propaganda consisting of twelve to twenty experts recruited by the newly formed National Union of Fascist Agricultural Technicians. [18]These commissions reproduced lectures and courses for local farmers, distributed leaflets and advertisements, and cultivated demonstration fields, all in order to make the case for proper rotation, good cultivation methods, application of fertilizers, and the planting of selected seeds. Their extension work was inspired by the words of the Duce: “You, the technicians… shall awaken agricultural activity from where it was left behind by the old procedures, or accelerate it where something has already been done; you shall be the energizers reaching out everywhere, till the last village, till the last man.” [19]

Читать дальше