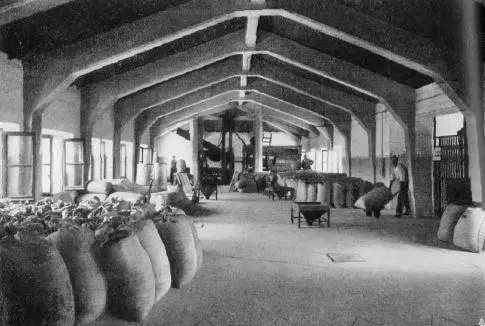

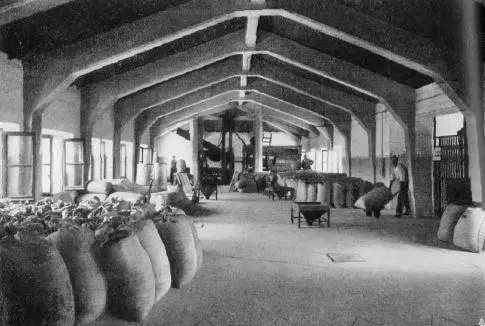

For northern and central Italy, where demand for the new strains was greater, it was the Rieti Experiment Station that was in direct control of the entire circuit. Making use of its large multiplication fields, the Station sold seeds to the Association of Seed Reproducers of Rieti, which had been formed in 1926 by the fascist government to encourage the use of Strampelli’s varieties. Strampelli himself was the technical director of the association, and his National Institute of Genetics partially funded its formation. The members of the association, all farmers in the Rieti region, were responsible for reproducing seeds under strict supervision of personnel from the National Institute of Genetics, who controlled every step from sowing to threshing. The seeds were then collected, separated, and packed in the association’s building, a major facility with ten silos. Seed bags, identified with the stamps of the Association of Seed Reproducers and the National Institute of Genetics, were distributed among the millions of farmers of northern and central Italy. It is not easy to decide who mobilized whom: was it the fascist state that mobilized Strampelli for the success of its Battle of Wheat, or was it the geneticist who mobilized the state to put his Ardito into circulation?

Figure 1.7 The building of the Association of Rieti Reproducers of Seed, 1932.

(Strampelli, “I Miei Lavori, p. 156)

And wheat circulation didn’t involve only farmers. Millers and bread consumers were also important. Indeed, when dealing with the science involved in the Battle of Wheat one is immediately struck by the amount of literature dedicated to the subject of rationalizing bread production, discussing in great detail the physical and chemical properties of flour or the design of bakers’ ovens. [57]Such material deserves, to be sure, an entire volume. Here it will be enough to mention that Strampelli’s strains, particularly Ardito , were objects of a controversy involving their quality for bread production. [58]In comparison with traditional Italian wheats, and with imported hard wheats such as Manitoba , Ardito was said to have worse dietary properties and to be ill adapted to bakers’ processes. And this was a time when bread consumers all over Europe increasingly valued whiter and lighter breads requiring specific properties of the wheat gluten, which justified the millers’ preference for high-strength flours. [59]The very same baking technology that transformed baking from a manual activity into a mechanized one also demanded stronger flours. Thus, while Strampelli conducted experiments to demonstrate the good technological properties of Ardito flours, the government decreed in 1931 that millers and bakers were required to use at least 95 percent Italian wheat in the production of bread and pasta. Strampelli’s National Institute of Genetics for Grain Cultivation, which had just moved into its new building in the outskirts of Rome, was granted a technological laboratory with a pilot facility for milling, baking, and pasta making, with the aim of demonstrating the superiority of national wheats.

While the experimental fields in Rieti or in Foggia enhanced the circulation of Strampelli’s hybrids on larger scales, the modest ovens and mills of the Technological Laboratory in Rome made them circulate among millers and consumers. Such instruments were crucial in guaranteeing that Italians were eating proper bread or pasta following autarkic principles. No true Italian was to use flour made from Manitoba wheat. [60]Again, it makes little sense to talk here about propaganda without substance, as too many scholars have referred to the Battle of Wheat, when such strong connections were being woven between millions of farmers, bakers, consumers, and the state by way of circulating geneticists’ artifacts.

This characterization of the effects of the Battle of Wheat should not = be taken as praise for the initiative. In fact, as Italian historians have insisted, the first beneficiaries of the new strains were the large landowners of the fertile Po Valley, confirming the popular saying “elite races for elite farmers.” [61]Protected from external competition by high customs duties and having access to easy credit and to a cheap labor pool kept under terror by the paramilitary Blackshirts, they greatly increased their incomes by selling the high-yield Ardito at high prices. In contrast, the spread of Strampelli’s varieties among small landowners, especially among sharecroppers whom the regime had promised to defend, didn’t stop their debts from rising during the fascist years. Difficult access to credit and the larger investments demanded by the new strains only contributed to increasing the number of rural people that migrated to urban centers against the explicit aims of the regime. The hardening of the genetic identity of the new wheat strains also exacerbated social inequalities. [62]

The following testimony is from Emanuele De Cillis, one of the agriculture experts who made up the Permanent Wheat Committee, concerning the introduction of new varieties into the underdeveloped Mezzogiorno in southern Italy:

The local soft wheats are impure races, formed by several genotypes, mixed in balanced proportions in function of the different environments:… they are thus more rustic, less demanding, more resistant to meteorological variations. They have much more balanced productions, but always modest ones…. The elite races are much more productive but also much more demanding. They are more susceptible to adverse weather conditions and this lower resistance can only be corrected through improved cultivation methods…. To promote the introduction of new early soft wheat in places one can not cultivate using the processes modern technique prescribes is absurd. [63]

The network of experiment stations and fields put in place by Strampelli determined for each location the proper amount and quality of fertilizers, rotation cycles, sowing distance, soil preparation, and all the other agricultural factors that one had to control for to express the high-yield properties of his new strains. In other words, in order for Ardito to circulate from the geneticist’s experimental plot to the farmers’ fields, the fields had to be converted into spaces reproducing the laboratory conditions of the experiment station. In spite of all the propaganda effort that went into the Battle of Wheat, the fascist state did not guarantee each and every farmer, small landholder, or sharecropper the tools for cultivating the land using the procedures deemed adequate for each new technoscientific organism.

If the fascist regime was not able to keep up to its promises, this doesn’t mean that Ardito was not effective. The astonishing numbers of its presence (along with other new strains) throughout the whole Italian territory and the wiping out of traditional landraces confirm the major effects of the initiative. The high-yield wheats increased rural debt among sharecroppers and small landholders, which indicates that Italians who were previously limited to a local economy were now participating in a national one, even when this didn’t bring them any major monetary return. Millions of farmers and peasants were now sustaining major chemical conglomerates, one of the main industrial investments of the fascist government. There is no doubt the battle was fought on the backs of overexploited and repressed wage laborers as well as of sharecroppers, but the fascists had been able to tighten national interdependences, with the growth of new industrial undertakings based on the produce of the national soil. Strampelli’s new organisms had in fact been able to weave new ties between Italians, contributing to the strengthening of the national community envisioned by fascists, even when large numbers of its members were poorer than before. The lodging-resistant Ardito delivered on the fascists’ promise of stronger nationalism but not on the promise of egalitarianism.

Читать дальше