In 1929, only three years after the military coup d’état that inaugurated in Portugal the authoritarian regime that would endure until 1974, the dictatorship launched a national mobilization for bread self-sufficiency evoking the enormous weight of wheat in Portugal’s commercial deficit. [22]The campaign was the final result of several initiatives since the mid 1920s to promote wheat production and support wheat protectionism against the menace of cheap foreign grain. These initiatives were undertaken by large landowners and their organizations, such as the Central Association of Portuguese Agriculture, in which Pequito Rebelo was a prominent figure. The Bread Week (1924), the National Congress of Wheat (1929), the Wheat Train (1928), the “best wheat spike” contest (1928), and a series of articles published in O Século , in Diário de Lisboa and in other major national newspapers were all direct precursors of the Wheat Campaign, officially launched in 1929 with explicit reference to the example of fascist Italy and the Battaglia del Grano. [23]

The mobilization for the production of the most basic good—bread—brought together big landowners selling cereal at prices guaranteed by the state, agricultural machine builders, chemical industries producing fertilizers, and masses of sharecroppers reclaiming land.

There is a consensus in the literature that the campaign should not be seen exclusively from the point of view of agriculture. [24]The major reason for this is probably the obvious role played in it by Companhia União Fabril (CUF), which, with its 6,000 workers, was the biggest chemical conglomerate on the Iberian Peninsula at the time. From 1927 until 1934, Portugal’s production of fertilizers more than doubled, which more than justified the CUF’s financing of demonstration fields and other propaganda actions praising the use of its fertilizers to win the Wheat Campaign. [25]Above, I insisted in the importance of the connections between chemical industry and agriculture for Italian fascism established through Strampelli’s Ardito . In looking at the Portuguese Wheat Campaign, I want to go a step further and delve into the ways new wheat strains contributed to the first institutional forms of the Portuguese fascist corporatist state. [26]As we will see, after the campaign an entire new set of corporatist institutions was created, with the National Federation of Wheat Producers (Federação Nacional de Produtores de Trigo) controlling production and commercialization at the national level, Farmers’ Guilds (Grémios da Lavoura) gathering landowners in regional structures, and Houses of People (Casas do Povo) locally undertaking peasant basic welfare initiatives. [27]

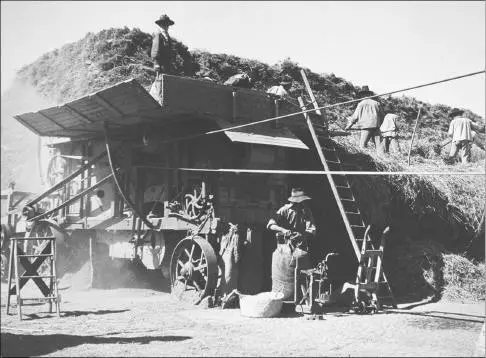

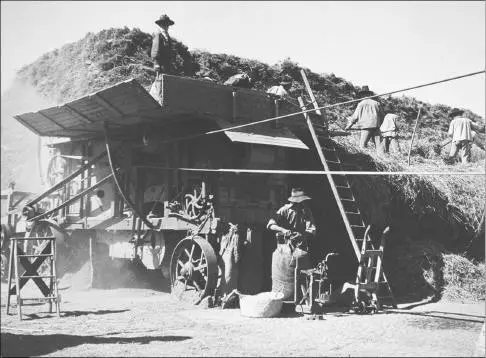

Figure 2.2 Artur Pastor, “Threshing Wheat in Alentejo, 1940.”

(Fundo Artur Pastor, Arquivo Municipal de Lisboa)

The campaign was a first step in the corporatist experiment of organizing society through associations of producers rather than classes, promising a less divisive and more organic form of political representation. It transformed a simple dictatorial regime into a fascist one, combining state corporatism and authoritarianism. [28]By 1933 the 1926 authoritarian military coup had evolved into a full-fledged fascist regime—the New State—with a corporatist constitution that would last until 1974. [29]It replaced any form of liberal mechanisms of representation with ideological nationalism, a one-party state, systematic political repression, and a social and economic corporatism formed by alleged organic social unities, a combination that placed it among the family of European fascist regimes. [30]Amusingly similar to Bolshevik arguments, the ruling elite of the New State considered Portuguese society not yet ready for pure corporatism from below, the state having to assume for the time being the responsibility to build a new social structure based on the alleged harmony of its different organs. Manuel de Lucena, a scholar who has explored the relations between corporatism and fascism in greater depth, maintains that not even in Mussolini’s regime were corporatist organizations so influential. [31]A short glance at the multiplicity of new institutes, boards, commissions, and councils, the so-called organisms of economic coordination, which were created to guarantee the discipline of different economical sectors, confirms the verdict. Every major product or raw material, be it rice, wine, cod, cotton, or wool and industries as disparate as milling, cannery, ceramics, or pharmaceutical, deserved a new rationalizing para-state corporatist institution controlling imports, prices, wages, or quality. [32]The first such corporatist institution to be created was the National Federation of Wheat Producers (FNPT), and it was the direct result of a campaign—in this case, the Wheat Campaign.

Colonel Henrique Linhares de Lima, having been responsible for organizing the management of supplies of the Portuguese Army in the trenches of World War I, was now to transfer his military expertise to the Wheat Campaign as Minister of Agriculture of the dictatorial regime from 1929 until 1932. Again, it is important to notice these constant transactions between peace and war, with permanent mobilization a hallmark of the new regimes. Linhares de Lima was granted the power to mobilize every engineer and scientist from the Lisbon Agronomy Institute—the main agricultural-sciences establishment in the country—to promote wheat production. He was quick to nominate the institute’s young and promising professor of genetics, António Sousa da Câmara, as the Wheat Campaign’s field marshall. [33]Câmara, when remembering those glorious days, didn’t shy away from the typical epic rhetoric of the fascist era: “The wheat campaign had come. The dawn had arrived! Happy those like us, who started our professional lives under the dawn’s early light and were able from the very first moment to follow a Great Leader and the flame of a new Mystique.” [34]The Great Leader was, of course, António de Oliveira Salazar (1889–1970), the dictator who headed the Portuguese government from 1932 until 1968, and who had been the finance minister of the dictatorial government since 1928.

Figure 2.3 António Sousa da Câmara, 1901–1971.

(Arquivo Histórico Parlamentar)

The Wheat Campaign was organized in six divisions—Propaganda, Technical Assistance, Financial Assistance, Transportation, Fertilizers, Seeds—with a triangular command made up of a politician named by the Minister of Agriculture, a large landowner, and an agricultural scientist. [35]Mário de Azevedo Gomes, the scientist formerly responsible for the technical services of the Ministry of Agriculture, did not hide his disdain for the new structure of the Central Board for the Wheat Campaign, which he described as an “alien body that represented a State inside the State.” [36]However, for Câmara there was no doubt concerning the need for this new parallel structure that should be filled with young people full of enthusiasm to serve the new leader. In the pages of his campaign diary, he recalled how Linhares de Lima was obsessed with “saving for the Nation the torrents of gold sent abroad to buy our bread. Salazar needs us to win the campaign.… If Salazar does not rest, neither do we have the right to rest.” [37]While Salazar tightened control over public expenditure to free Portugal from foreign dependency, the Wheat Campaign, together with measures increasing protectionism and credit concessions, promoted national production and imports substitution. [38]

Читать дальше