Here is what we do know: cunt is the oldest word for either the vulva or the vagina in the English language (possibly the oldest in Europe). Its only rival for oldest term for ‘the boy in the boat’ (1930) would be yoni (meaning vulva, source or womb). The English language borrowed yoni from ancient Sanskrit around 1800 and today it has been appropriated by various neo-spiritual groups who hope that by calling their ‘duff’ (1880) a yoni they can avoid the horror of cunt and tap into some ancient veneration of the ‘flapdoodle’ (1653). Of course, the irony is cunt and yoni may even have sprung from the same Proto-Indo-European root. Furthermore, cunt is far more feminist than vagina or vulva could ever dream to be.

Vagina turns up in seventeenth-century medical texts and comes from the Latin vagina , which means a sheath or a scabbard. A vagina is something a sword goes into; that’s its entire etymological function – to be the holder of a sword (penis). It relies on the penis for its meaning and function. We may as well still be calling the poor thing ‘cock alley’ (1785) or the ‘pudding bag’ (1653). There are many cunning linguists who rightly get their proverbials in a twist when you confuse vagina with vulva: to be clear, the vagina is the muscular canal that connects the uterus to the vulva, and the vulva is the external equipment (comprising the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, vestibule of the vagina, bulb of the vestibule, and the Bartholin’s glands). Vulva dates to the late fourteenth century and comes from the Latin vulva , meaning ‘womb’ – some have suggested it comes from volvere , or to wrap. In his 1538 Latin dictionary, Thomas Elyot defined a vulva as ‘the womb or mother of any female animal, also a meat used of the Romans made of the belly of a sow, either that hath farrowed or is with farrow’. {7} 7 Quoted in Mohr, Holy Sh*T , p. 149.

So, yet again, the meaning of vulva is dependent on being the container for a penis – or a questionable cut of a pregnant Roman pig.

Cunt, however, predates both these terms and derives from a Proto-Indo-European root word meaning woman, knowledge, creator or queen, which is far more empowering than a word that means ‘I hold cock’. Plus, cunt is the whole damn shebang, inside and out. There’s no need to split pubic hairs when it comes to cunt. Words like vulva and vagina are linguistic efforts to offer sanitised, medicalised alternatives to cunt. And if that wasn’t enough to sway you over to team cunt, in 1500 Wynkyn de Worde defined vulva as ‘in English, a cunt’. {8} 8 Ibid.

Cunt is not slang; cunt is the original. So, cunt is the godmother of all words for ‘the monosyllable’ (1780) – but then the question arises: has cunt always been such an offensive word as it is today?

The simple answer is no. To the medieval mind, cunt was simply a descriptive word, a little bawdy perhaps as cunts tend to be, but certainly not offensive. The fact that cunt would make it into de Worde’s dictionary and medical texts shows how everyday the word was. John Hall’s sixteenth-century translation of Lanfranc of Milan’s medical text Chirurgia Parua Lanfranci is not cunt shy and describes ‘in wymmen neck of the bladder is schort, is made fast to the cunte’. {9} 9 Lanfranco and John Hall, Most Excellent and Learned Worke of Chirurgerie, Called Chirurgia Parua Lanfranci , 1st edn (London: Marshe, 1565).

The earliest cunt citation in the Oxford English Dictionary dates to 1230, and is a London street in the red-light district of Southwark – the beautifully named ‘Gropecuntelane’. {10} 10 ‘Cunt’, Oed.com , 2018 < http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/45874?redirectedFrom=cunt#eid > [Accessed 7 September 2018].

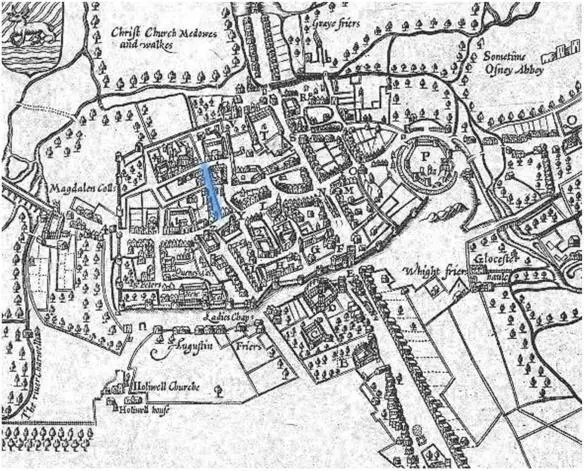

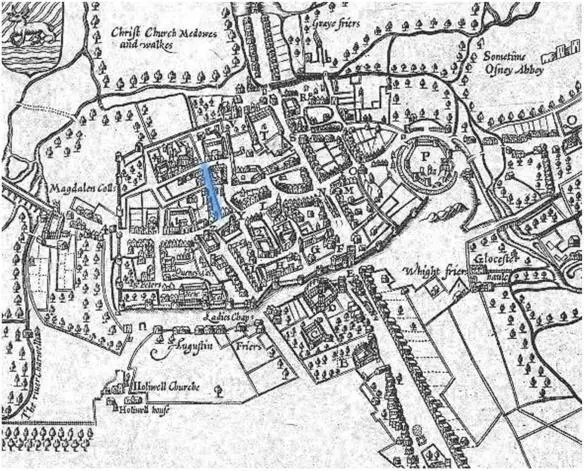

It did exactly what it said on the tin: it was a lane for groping cunts. There were Gropecuntelanes (or variations of Grapcunt, Groppecuntelane, Gropcunt Lane) found throughout the cities of medieval Britain. Keith Briggs locates Gropecuntlanes in Oxford, York, Bristol, Northampton, Wells, Great Yarmouth, Norwich, Windsor, Stebbing, Reading, Shareshill, Grimsby, Newcastle and Banbury. Sadly, all of these streets have now been renamed, usually as ‘Grape Lane’ or ‘Grove Lane’. {11} 11 ‘OE and ME Cunte in Place-Names’, Keith Briggs , 2017 < http://keithbriggs.info/documents/cunte_04.pdf > [Accessed 5 April 2017].

While Scottish folk may be calling their friends cunts, medieval people seem to have been calling their children cunts. Cunt actually turns up in a number of medieval surnames (though they are quite possibly aliases): Godwin Clawecunte (1066), Gunoka Cuntles (1219), John Fillecunt (1246) and Robert Clevecunt (1302) have all been recorded. And if the possibility of meeting Miss Gunoka Cuntles on Gropecuntelane was not an exciting enough prospect (and it should be), a Miss Bele Wydecunthe appears in a Norfolk Subsidy Roll of 1328. {12} 12 ‘Oxford English Dictionary’, Oed.Com , 2018.

While we are on the subject of cunt monikers, in his study of humorous names, Russell Ash found a whole family of Cunts living in England in the nineteenth century: Fanny Cunt (born 1839), also her son, Richard ‘Dick’ Cunt, and her daughters, Ella Cunt and Violet Cunt. {13} 13 Russell Ash, Busty, Slag and Nob End (London: Headline, 2009), Kindle edition, location 665.

John Speed, Map of Oxfordshire and the University of Oxford , 1605 . Gropecuntelane is shown in blue.

Medieval literature is similarly awash with cunts. The Proverbs of Hendyng ( c . 1325) contains this advice to young women: ‘Give your cunt cunningly and make (your) demands after the wedding’ (ʒeve þi cunte to cunni[n]g, and craue affetir wedding). {14} 14 ‘Oxford English Dictionary’, Oed.Com , 2018.

The fifteenth-century Welsh poet Gwerful Mechain advised fellow poets to celebrate the ‘curtain on a fine bright cunt’ that ‘flaps in a place of greeting’. {15} 15 Liz Herbert McAvoy and Diane Watt, The History of British Women’s Writing, 700–1500 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), p. 68.

Medieval society was far more sexually liberated than we give them credit for, and one reason cunt wasn’t considered offensive is because sex wasn’t that offensive to them. It was certainly not a sexually liberated utopia, but neither were medieval people waddling about in chastity belts, as popular mythology would have us believe. Sex was a source of great humour, eroticism and absolutely central to married life; finding sex deeply offensive is something that came into its own during the early modern era.

A twelfth-century sheela na gig on the church at Kilpeck, Herefordshire, England.

Historically, the most heavily tabooed language has shifted from the blasphemous to bodily functions, and is now in a process of moving to race. Swear words that would get you into serious trouble in the Middle Ages were blasphemous ones. If you caught your soft areas in a zipper in the thirteenth century, you might cry out something like ‘God’s teeth’, ‘God’s wounds’ (Z’wounds) or ‘God’s eyes’. Cunt, by comparison, was a descriptive word and suitable for all occasions. It was not euphemistically twee, overly medicalised or humorously grotesque – cunt was cunt.

One medieval author who dropped the C-bomb with the precision of a military drone is Geoffrey Chaucer (1343–1400). The word that Chaucer uses in The Canterbury Tales and House of Fame is not ‘cunt’ but ‘queynte’. However, the reader is left in little doubt as to what a queynte is – the Wife of Bath is quite clear:

Читать дальше