From the twelfth century, whore was a term of abuse for a sexually unchaste woman, but it did not specifically mean a sex worker. Thomas of Chobham’s thirteenth-century definition of a whore was any woman who had sex outside marriage (hands up all those who have just learned they are a thirteenth-century whore). {5} 5 Thomas De Chobham and F. Broomfield, Thomae De Chobham Summa Confessorum (Louvain: Nauwelaerts, 1968), pp. 346–7.

Shakespeare used ‘whore’ nearly a hundred times in his plays, including Othello , Hamlet and King Lear ; but in these plays it doesn’t mean someone who sells sex, it means a promiscuous woman. John Webster’s The White Devil (1612) explores narratives around badly behaved women. In one memorable scene Monticelso defines what a whore is:

Shall I expound whore to you? sure I shall;

I’ll give their perfect character. They are first,

Sweetmeats which rot the eater; in man’s nostrils

Poison’d perfumes. They are cozening alchemy;

Shipwrecks in calmest weather. What are whores!

Cold Russian winters, that appear so barren,

As if that nature had forgot the spring.

They are the true material fire of hell:

Worse than those tributes i’ th’ Low Countries paid,

Exactions upon meat, drink, garments, sleep,

Ay, even on man’s perdition, his sin.

They are those brittle evidences of law,

Which forfeit all a wretched man’s estate

For leaving out one syllable. What are whores!

They are those flattering bells have all one tune,

At weddings, and at funerals. Your rich whores

Are only treasures by extortion fill’d,

And emptied by curs’d riot. They are worse,

Worse than dead bodies which are begg’d at gallows,

And wrought upon by surgeons, to teach man

Wherein he is imperfect. What’s a whore!

She’s like the guilty counterfeited coin,

Which, whosoe’er first stamps it, brings in trouble

All that receive it. {6} 6 John Webster, The White Devil , in John Webster, Three Plays, ed. by David Charles Gunby (London: Penguin Books, 1995), pp. 84–5.

Monticelso doesn’t admit it, but what is driving this rant is a fear of women, fear that they can wield power over men; they can ‘teach man wherein he is imperfect’. Here, a whore is not a sex worker, she is a woman who has authority over a man and must be shamed into silence at all costs.

Historically, ‘whore’ has been used to attack those who have upset the status quo and asserted themselves, usually in an attempt to reassert sexual control and dominance over her. But unlike the word ‘prostitute’, whore is not tied to a profession but to a perceived moral state. Which is why many powerful women, with no connection to the sex trade, have been attacked as ‘whores’; Mary Wollstonecraft, Phulan Devi, even Margaret Thatcher were all labelled whores. The word is an attempt to shame, humiliate and ultimately subdue its target, and your average woman on the street is just as likely to be called a whore as a world leader, perhaps even more so.

‘Whore’ is a nasty insult today, but calling someone a whore in the early modern period was regarded as such a serious defamation of character that you could be taken to court for slander. [1] Three excellent sources to read more about Tudor slander courts are Dinah Winch, ‘Sexual Slander and its Social Context in England c . 1660–1700, with Special Reference to Cheshire and Sussex’ (unpublished PhD thesis, The Queen’s College, Oxford University, 1999); Bernard Capp, When Gossips Meet: Women, Family, and Neighbourhood in Early Modern England (Oxford Studies in Social History) (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003); and Rachael Jayne Thomas, ‘“With Intent to Injure and Diffame”: Sexual Slander, Gender and the Church Courts of London and York, 1680–1700’ (unpublished MA, University of York, 2015).

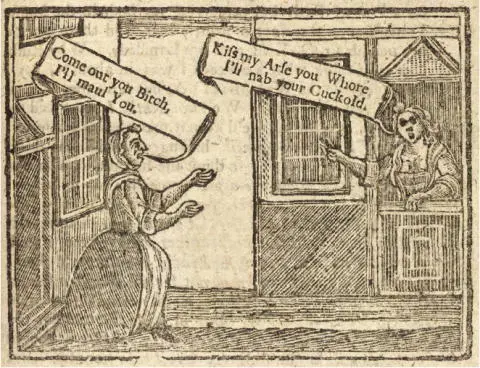

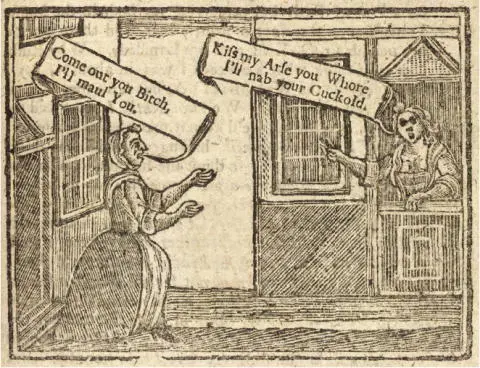

By far the most frequent insult cited in these cases where a woman has been slandered is ‘whore’ and myriad creative variants thereon: ‘stinking whore’, ‘ticket-buying whore’, ‘drunken piss-pot whore’, ‘lace petticoat whore’ and ‘dog and bitch whore’ have all been recorded. {7} 7 Rachael Jayne Thomas, ‘“With Intent to Injure and Diffame”: Sexual Slander, Gender and the Church Courts of London and York, 1680–1700’ (unpublished MA, University of York, 2015), pp. 134–5.

In 1664, Anne Blagge claimed that Anne Knutsford had called her a ‘poxy-arsed whore’. {8} 8 ‘Anne Knutsford c. Anne Blagge’ (Chester, 1664), Cheshire Record Office, EDC5 1.

Poor Isabel Yaxley complained of a neighbour alleging that she was a ‘whore’ who could be ‘fucked for a pennyworth of fish’ in 1667. {9} 9 Quoted in Bernard Capp, When Gossips Meet: Women, Family, and Neighbourhood in Early Modern England (Oxford Studies in Social History) (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003) , p. 193.

In 1695, Susan Town of London accused Jane Adams of shouting to ‘come out you whore, and scratch your mangy arse as I do’. {10} 10 ‘Susan Town c. Jane Adams’ (London, 1695), London Metropolitan Archives, DL/C/244.

In 1699, Isabel Stone of York brought a suit against John Newbald for calling her ‘a whore, a common whore and a piss-arsed whore… a Bitch and a piss-arsed Bitch’. {11} 11 ‘Cause Papers’ (York, 1699), Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York, CP.H.4562., p. 3.

And in 1663, Robert Heyward was hauled before the Cheshire courts for calling Elizabeth Young a ‘salt bitch’ and a ‘sordid whore’. In court he claimed he could prove Elizabeth was a whore and she should just go home and ‘wash the stains out of thy coat’. {12} 12 ‘Elizabeth Young c. Robert Heyward’ (Chester, 1664), Cheshire Record Office, CRO EDC5 1663/64.

Examples of ‘unfeminine language’ from New Art of Mystery of Gossipping , 1770.

In order to prove a case of slander, you would need a witness to the insult, to prove the accusation was untrue with a character witness, and to show how your reputation had been damaged by being called such names. The punishment for slander ranged from fines and being ordered to publicly apologise, through to excommunication (though this was rare). One example of punishment occurred in 1691, when William Halliwell was ordered to publicly apologise in church to Peter Leigh for defaming his character:

I William Halliwell forgetting my duty to walk in Love and Charity towards my neighbour have uttered spoken and published several scandalous defamatory and reproachful words of and against Peter Leigh… I do hereby recant revoke and recall the said words as altogether false scandalous and untrue… I am unfeignedly sorry and I hereby confess and acknowledge that I have much wronged and injured him. {13} 13 ‘Peter Leigh c. William Halliwell’ (Chester, 1663), Cheshire Record Office, CRO EDC5 1663/63.

The accusation of ‘whore’ was particularly damaging as it directly affected a woman’s value on the marriage market. So when Thomas Ellerton called Judith Glendering a ‘whore’ who went from ‘barn to barn’ and from ‘tinkers to fiddlers’ in 1685, he was doing more than being abusive, he was preventing her finding a husband. {14} 14 ‘Judith Glendering c. Thomas Ellerton’ (London, 1685), London Metropolitan Archives, DL/C/241.

In 1652, Cicely Pedley alleged she had been called a ‘whore’ with the intention ‘to prevent her marriage with a person of good quality’. {15} 15 ‘Cicely Pedley c. Benedict and Elizabeth Brooks’ (Chester, 1652), Cheshire Record Office, PRO Ches. 29/442.

It could even affect business. In 1687, a Justice of the Peace decided that calling an innkeeper’s wife a ‘whore’ was actionable because it had affected trade. {16} 16 Dinah Winch, ‘Sexual Slander and its Social Context in England c. 1660–1700, with Special Reference to Cheshire and Sussex’ (unpublished PhD thesis, The Queen’s College, Oxford University, 1999), p. 52.

Читать дальше