There are numerous slander cases brought by a husband whose wife had been called a whore. Calling someone’s wife a whore was a particularly devastating insult as it not only insulted the wife, but also impugned the husband as a cuckold and questioned his ability to sexually satisfy the missus. In 1685, for example, Abraham Beaver was accused of ordering Richard Winnell to ‘get thee home thou cuckold thou will find Thomas Fox in Bed with thy Wife’. {17} 17 ‘Martha Winnell c. Abraham Beaver’ (York, 1685), Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York, CP.H.3641.

Although cases of men alleging slander were less frequent, they too were often sexual in nature. In 1680, Elizabeth Aborne of London was taken to court by Thomas Richardson for saying that his penis was ‘rotten with the pox’. {18} 18 ‘Thomas Richardson c. Elizabeth Aborne’ (London, 1690), London Metropolitan Archives, DL/C/243.

Men were also attacked as ‘whoremongers’, ‘cuckolds’, ‘bastard-getters’, ‘rogues’, and in one case a ‘jealous pated fool and ass’. {19} 19 Thomas, ‘With Intent to Injure and Diffame’, p. 142.

Men brought cases against people who had called them thieves, beggars or drunkards. In 1699, for example, Thomas Hewetson was brought before the courts in York for calling Thomas Daniel a ‘mumper’ (beggar): ‘he was a mumper and went about the Country from door to door mumping’. {20} 20 ‘Thomas Hewetson c. Thomas Daniel’ (London, 1699), London Metropolitan Archives, CP.H.4534.

By the end of the seventeenth century, there was a notable decline in the number of slander cases brought before the Church courts. Historians have long debated why this may have been the case. It may be that as cities swelled and the population grew, the courts became more concerned with crimes other than women calling each other ‘hedge whores’ and ‘poxy-arsed whores’. It may just be that there was a shift in culture and taking your slagging matches before a judge became less the done thing. By 1817, UK law ruled that ‘calling a married woman or a single one a whore is not actionable, because fornication and adultery are subjects of spiritual not temporal censures’. {21} 21 William Selwyn, An Abridgment of the Law of Nisi Prius (London: Clarke, 1817), p. 1004.

Google Ngram Viewer: frequency of the word ‘whore’ recorded in English literature from 1500 to 2008.

As the above chart shows, since the seventeenth century there has been a notable decline in the use of the word ‘whore’. Until the end of the seventeenth century, ‘whore’ was still a legal term and turns up in no less than 163 trials at the Old Bailey from 1679 until 1800. Historians such as Rictor Norton have examined how ‘prostitute’ or ‘common prostitute’ came to replace ‘whore’ as the legal terminology for a person who sells sexual services. {22} 22 ‘The word “whore” occurs in a total of 163 trials at the Old Bailey up to 1800: From the first occurrence in 1679 through 1739, 66 trials (just over 40 per cent); from 1730 through 1769, 61 (just over 37 per cent); from 1770 through 1799, 36 (22 per cent)’. (‘History of the Term “Prostitute”’, Essays by Rictor Norton , 2018 < http://rictornorton.co.uk/though15.htm > [Accessed 10 August 2018].)

I suspect the sharp decline in the usage of ‘whore’ at the end of the seventeenth century is linked to the linguistic shift from legal terminology to a pure insult.

Today, ‘whore’ is largely confined to abusive and coarse speech. However, like the word ‘slut’, ‘whore’ is also in a state of reclamation and can be used to directly challenge the shame the word has carried for hundreds of years. ‘Whore’ may be a term of abuse, but it is one rooted in fear of female independence and sexual autonomy. Its progression from meaning a woman who desires, to an insult seeking to shame that desire, traces cultural attitudes around female sexuality. I do not use ‘whore’ to shame, I use it to recognise all those who rattled cultural sensibilities enough to be called a whore. I use it to deflate the shame within it. I use it to remember that our language shapes how we view each other, and it is constantly evolving. Historically, if you desire, you are a whore; if you have sex outside of marriage, you are a whore; if you transgress and threaten ‘the man’, you are a whore. We are all historical whores.

‘A Nasty Name for a Nasty Thing’

A History of Cunt

Ilove the word cunt. I love everything about it. Not just the signified vulva, vagina and pudendum (which are all kinds of cunty goodness and will be returned to shortly), but the actual oral and visual signalled sign of cunt. I love its simple monosyllabic form. I adore that the first three letters (c u n) are basically all the same chalice shape rolling though the word until they are stopped in their ramble by the plosive T at the end. I love the forceful grunt of the C and the T sandwiching the softer UN sounds, enabling one to spit the word out like a bullet, or extend the un and roll it around your mouth for dramatic effect: cuuuuuuuuuuuunt!

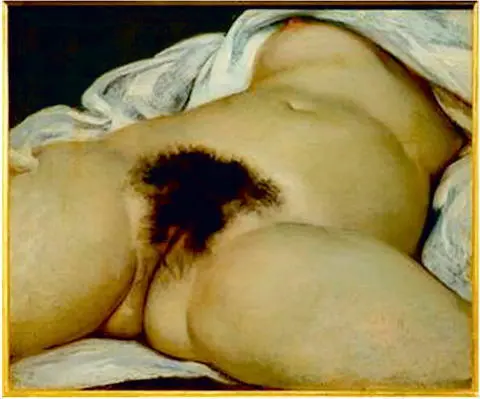

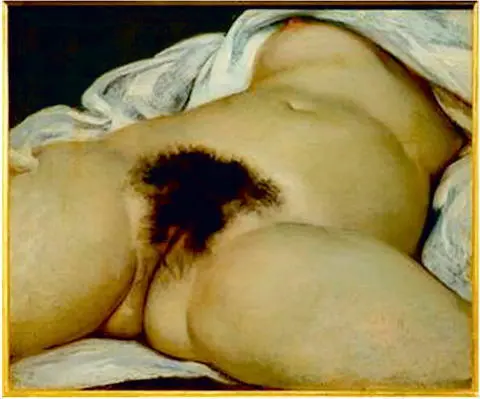

Gustave Courbet, L’Origine du Monde , 1866.

I love it because it’s deliciously dirty, endlessly funny and, like an auditory exclamation mark, is capable of stopping a conversation in its tracks. Walter Kirn called cunt ‘the A-bomb of the English language’, and he’s absolutely right. {1} 1 Walter Kirn, ‘The Forbidden Word’, GQ , 4 May 2005, p. 136.

I love its versatility. In America, it is spectacularly offensive, while in Glasgow it can be a term of endearment; ‘I love ya, ya wee cunt’ is an expression heard throughout Glaswegian nurseries. That’s not true, but Scottish folk do possess a dazzling linguistic dexterity with cunt. Irvine Welsh’s 1993 novel Trainspotting contains 731 cunts (though only nineteen made it into the film).

But more than anything else, I love the sheer power of the word. I am fascinated by cunt’s hallowed status as, to quote Christina Caldwell, ‘the nastiest of the nasty words’. {2} 2 Christina Caldwell, ‘The C-Word: How One Four-Letter Word Holds So Much Power’, College Times , 15 March 2011.

There are other contenders for the ‘most offensive’ word in the English language; racial slurs are obvious heavyweights. The N-word is a deeply offensive word because of its historical context. It is not just a descriptive word, it is a word that was used to dehumanise black people and justify some of the worst atrocities in human history. It enabled the enslavement and brutalisation of millions of people by linguistically denying black people equality with white people. We can understand why racial slurs are hideously offensive, but cunt? Does it not strike anyone else as odd that one of the most offensive words in English is a word for vulva? Or that this word could even be considered in the same league of offence as racist terms spawned from the darkest and most rank of human atrocities? As far as I am aware, cunt has not enabled racial genocide, so we have to ask: how did cunt get to be so offensive? What did cunt do wrong?

Let’s turn to the etymology first. Cunt is old. It’s so old that its exact origins are lost in the folds of time and etymologists continue to debate where in the cunt cunt comes from. It’s several thousand years old at least, and can be traced to the old Norse kunta and Proto-Germanic kunt , but before that cunt proves quite elusive. There are medieval cunty cognates in most Germanic languages; kutte , kotze and kott all appear in German. The Swedish have kunta ; the Dutch have conte , kut and kont , and the English once had cot (which I quite like and think is due a revival). [2] ‘Oxford English Dictionary’, Oed.Com , 2018 < http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/45874?redirectedFrom=cunt#eid > [Accessed 7 September 2018]. Other excellent sources that cover the etymology of cunt include Mark Daniel, See You Next Tuesday (London: Timewell, 2008); Pete Silverton, Filthy English (London: Portobello Books, 2009); Jonathon Green, Green’s Dictionary of Slang (London: Chambers, 2010); Melissa Mohr, Holy Sh*T: A Brief History of Swearing (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013); and Matthew Hunt, ‘Cunt’, Matthewhunt.Com , 2017 < http://www.matthewhunt.com/cunt/ > [Accessed 3 September 2018].

Here’s where the debate comes in: no one is quite sure what cunt actually means. Some etymologists have argued cunt has a root in the Proto-Indo-European sound ‘ gen / gon’ , which means to ‘create, become’. You can see ‘gen’ in the modern words gonads, genital, genetics and gene. Others have theorised cunt descends from the root gune , which means ‘woman’ and crops up in ‘gynaecology’. {3} 3 Pete Silverton, Filthy English (London: Portobello Books, 2009), p. 52; Matthew Hunt, ‘Cunt’, Matthewhunt.Com , 2017 < http://www.matthewhunt.com/cunt/ > [Accessed 03 September 2018].

The root sound that most fascinates etymologists is ‘cu’. ‘Cu’ is associate with the female, and forms the basis of ‘cow’ and ‘queen’. {4} 4 Mark Daniel, See You Next Tuesday (London: Timewell, 2008), Kindle edition, location 135.

‘Cu’ is linked to the Latin cunnus (‘vulva’), which sounds tantalisingly like cunt (though some etymologists claim it is unrelated), and has spawned the French con , the Spanish coño , the Portuguese cona , and the Persian kun . [3] کون

{5} 5 Melissa Mohr, Holy Sh*T: A Brief History of Swearing (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 20.

My favourite cunt theory is that the ‘cu’ also means to have knowledge. Cunt and ‘cunning’ are likely to have descended from the same root – ‘cunning’ originally meant wisdom or knowledge, rather than sneakiness, while ‘can’ and ‘ken’ became prefixes to ‘cognition’ and other derivatives. {6} 6 Silverton, Filthy English , p. 52.

In Scotland today, if you ‘ken’ something, it means you understand it. In the Middle Ages ‘quaint’ meant both knowledge and cunt (but more of that later). The debate will rage on, but the bottom line is that cunt is something of a mystery.

Читать дальше