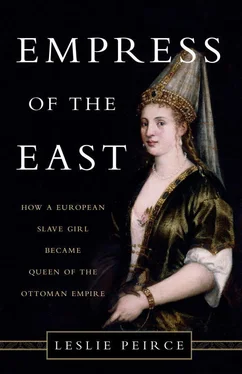

Whether Roxelana was a high-value gift or merely a promising slave matters to our appreciation of her unprecedented success. A gift slave came ready with sophisticated training. Her donor’s best hope was that she would become an intimate of the sultan. If Suleyman chose not to make her a concubine or even to take her to his bed for one night, her value would at least protect her from menial status. If, however, Roxelana was merely one among the many purchased at market who were working their way up the Old Palace ranks, she had only her wits and guts and whatever innate physical appeal she possessed to propel her.

What had Roxelana’s sellers, buyers, mistresses, and masters seen in the Russian slave girl that motivated them to take her so far? Pietro Bragadin, Venetian ambassador during the early years of Suleyman’s reign, reported that the sultan’s new favorite was “young but not beautiful, although graceful and petite.” [10] Alberi, Relazioni , 3:101.

Physical attractiveness combined with a certain sexual guile was necessary in a royal concubine, but beauty was not the sole requisite. A healthy body was critical in someone whose mandate was to propagate the dynasty. Virginity, an essential condition, meant that Roxelana had remained unmolested during her passage from Ruthenia to the royal palace. But these physical attributes were worth little without intelligence. The real job of royal concubines, once they had aroused their master’s sexual interest, was to bear and then to raise royal children. A sharp mind along with a savvy instinct for political survival was a sine qua non in a culture that trusted the mother of a potential heir to prepare him for the sultanate. Roxelana had to demonstrate that she was a quick learner.

Like most slaves who entered Muslim households, Roxelana was converted to Islam at some point in her training. Along with her new religion, she received a new name, her former identity symbolically erased. As a new Muslim, she was taught to repeat the core Islamic creed—“There is no god but Allah, Muhammad is the messenger of Allah”—and to perform her daily prayers. She probably also learned to recite the Fatiha, the short opening chapter of the Qur`an, considered by many Muslims to express its essence. But Roxelana could not have made much, if any, headway with Islamic scriptures because their language was Arabic. Her first linguistic challenge was to acquire facility with Turkish, the tongue of the Ottoman dynasty and the lingua franca of cosmopolitan Istanbul. Turkish, written in the Arabic script, may also have been her first written language, although, if truly the daughter of a priest, she could perhaps recognize and even write her Cyrillic letters.

Roxelana would also need to master the body language and courtly poise appropriate to the Ottoman palace. The would-be concubine must learn how to carry herself and how to dress. She must know when to lower her gaze, when to bow, and whose hand to kiss and then touch to her forehead as a sign of respect. She must glean the etiquette of palace discourse: to whom she might speak, on what occasions, in what words—and, perhaps most important, when to remain silent.

Roxelana needed to demonstrate that she was not only astute but also loyal. Advancing to the threshold of the royal concubine’s career—presentation to the sultan—required the backing of patrons as well as personal skill. If Roxelana was the gift of a high-ranking individual, she already had a patron, but if she came to the Old Palace as a slave-market purchase, her own initiative in attracting support from her superiors was crucial. Because a successful concubine had the sultan’s ear, various individuals in the royal household would acquire a stake in her progress, helping her along the way in exchange for future favors. Roxelana’s advocates could point out how to balance deference with displays of intelligence and how to recognize the moment when a spark of flair could catch the notice of a key superior—or perhaps of the sultan himself.

WHEN ROXELANA ARRIVED in the Old Palace, she encountered an array of imposing women. First and foremost among them was Suleyman’s beloved mother Hafsa, apparently a favorite concubine of his father Selim. In his 1526 report to the Venetian Senate, Bragadin noted that she was “a very beautiful woman of forty-eight, for whom he bears great reverence and love.” [11] Ibid., 3:101.

During Suleyman’s European military campaign in the same year, he wrote personally to tell his mother the momentous news of his army’s rout of the Hungarian forces on the plain of Mohacs.

Contrary to the popular legend that claims Hafsa to be the daughter of a Crimean Tatar khan, she, like all concubines of the era, was almost surely an enslaved and converted Christian of unknown origin. However, as legends often do, this one may encapsulate a truth within its error, namely, that the girl who became Hafsa may have been abducted from the northern Black Sea region. Whatever Hafsa’s story, it was doubtless whispered to new recruits in Old Palace service. For these young women, she was surely a celebrity, what with her great beauty, her enormous success as a slave convert, and the aura that was beginning to surround her as mother to a “magnificent” son.

When Suleyman was sent out in 1509 to begin his princely apprenticeship, Hafsa was the dynastic elder at her son’s court at Caffa, capital of the Ottoman province that stretched along the northern Black Sea coast. (His father Selim remained in his own princely post on the sea’s southeastern coast at Trabzon.) Suleyman was fifteen when he became governor of Caffa, where the hierarchy of his harem began to take shape. Hafsa presided over her son’s domestic household for four years in Caffa and then, after Selim won the contest for his father’s throne in 1512, in the western Anatolian city of Manisa.

Salary registers dating from Suleyman’s tenure in Manisa signal Hafsa’s esteemed status. Her monthly stipend—6,000 silver aspers—was the highest figure on the princely payroll and triple the personal income of the prince himself. [12] BOA, D 8030, f. 1b.

Suleyman was still a junior member of the dynasty, despite the fact that he was his father’s only surviving son and heir and was already producing heirs of his own. When Selim died suddenly in 1520 and Suleyman became sultan, Hafsa simply adapted her role to the new scale of imperial life in Istanbul, acquiring greater status as queen mother. She was now a free woman under Islamic law, which provided protections for the concubine mother: she could not be sold or given away during her master’s lifetime, and upon his death she was automatically freed. This regard for the slave who bore a child to a free Muslim man stemmed in part from the fact that the law recognized the child as freeborn.

As Roxelana grew in prominence, she likely also came into direct contact with the Lady Steward, one of whose principal responsibilities was to supervise the select group who served the queen mother and, during his visits, the sultan. While this office was an old one, little is known about it before the late sixteenth century, when prominent members of the New Palace harem established by Roxelana became figures of political interest. The steward during Roxelana’s tenure, or at least part of it, may have been a woman called Gulfem, whom Roxelana mentions often in her letters to Suleyman. Steward or not, Gulfem was clearly helpful and supportive of the young concubine. In one letter, Gulfem appended a note explaining to the sultan how she had solved a budget problem for his favorite. Some have claimed, without evidence, that Gulfem was a former concubine of Suleyman whose offspring had died; if true, it appears that at some point he rewarded her for her talent and service with the stewardship.

Читать дальше