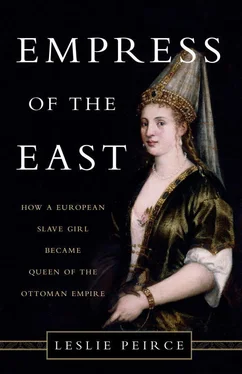

Leslie Peirce

EMPRESS OF THE EAST

HOW A EUROPEAN SLAVE GIRL BECAME QUEEN OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE

For Joanne, Lynda, Nancy, Linda,

and the memory of Jude

This woman, of late a slave, but now become the greatest empresse of the East, flowing in all worldly felicitie, attended upon with all the pleasures that her heart could desire, wanted nothing she could wish but how to find means that the Turkish empire might after the death of Solyman be brought to some one of her owne sons.

—Richard Knolles,

The Generall Historie of the Turkes (1603)

The Ottoman empire in the reign of Suleyman I.

This week there has occurred in this city a most extraordinary event, one absolutely unprecedented in the history of the Sultans. The Grand Signior Suleiman has taken to himself as his Empress a slave woman from Russia. …There is great talk about the marriage and none can say what it means.

—Dispatch from the Genoese Bank of Saint George, Istanbul representative

[1] Quoted in Young, Constantinople , 135.

THE RUSSIAN SLAVE had been the concubine of Suleyman I, “the Magnificent,” for fifteen years when the royal wedding celebration took place in 1536. Like all concubines of the Ottoman sultans, she was neither Turkish nor Muslim by birth. Abducted from her homeland, the young girl proved herself adaptable and quick-witted, mastering the rules, the graces, and the politics that propelled her from obscurity to the sultan’s bed. She rapidly became Suleyman’s favorite, astounding both his court and his public. Sultans of the Ottoman empire did not make demonstrable favorites of their consorts, however much they came to care for them. But Suleyman and Roxelana became the parents of six children in quick succession, five of them sons. Some thought Roxelana used seductive powers, even potions, to induce the love Suleyman appeared to bear her. They called her witch.

Together the royal couple overturned one assumption after another. Roxelana was the first Ottoman concubine ever to marry the sultan who was her master. She was also the first to cut an overtly conspicuous figure. It was Roxelana who transformed the imperial harem from a residence for women of the dynasty into an institution that wielded political influence. Royal women following in her footsteps crafted powerful roles in Ottoman politics while serving as advisers to their sons and, in the seventeenth century, ruling as regents. When Roxelana died in 1558, she also left as a tangible part of her legacy numerous charitable foundations in the Ottoman capital of Istanbul and across the empire—another break with tradition.

While there was no formal office of queen among the Ottomans, Roxelana filled this role in all but title, a formidable match for the great female rulers and consorts of Europe who shared the sixteenth century with her. But the radical nature of what can only be called the reign of Suleyman and Roxelana—a ruling partnership never repeated by the Ottomans—made her a controversial figure in her own time. The debate over her place in Ottoman history persists today.

Roxelana’s given name is not known. Nor are we certain of her exact birthplace, the date of her birth, or the names of her parents. But historical hearsay is plausible in her case because of the fascination she held for watchers of the Ottomans like the Genoese banker. Contemporary consensus held that she came from Ruthenia, “old Russia”—today a broad region in Ukraine—then governed by the Polish king. Europeans interested in her origins called her Roxelana, “the maiden from Ruthenia.”

The Ottoman name given to the young captive was Hurrem, a Persian word meaning “joyful” or “laughing.” Though she lived with this name for the rest of her life, she was rarely called it, except by Suleyman. Powerful people were known by their titles. To his subjects, Suleyman was “the Padishah,” the sovereign. As the monarch’s exclusive consort, Roxelana acquired the title “Haseki,” the favorite. When Suleyman made her a free woman and married her, she became the “Haseki Sultan” (the addition of “sultan” to a woman’s name or title indicated her membership in the dynastic family). This book calls her Roxelana, the name by which those outside the Ottoman world knew her and many still remember her.

Some Ottomans later came to believe that Roxelana was the daughter of an Orthodox priest—or so they told a Polish ambassador who came to Istanbul in the 1620s. But the only absolute certainty about the young captive is that her natal family was Christian. From the early fifteenth century onward, the sultans fathered all their children with Christian-born females taken from the empire’s borderlands or beyond. These captive females were converted to Islam and assimilated into Ottoman culture before they were chosen as royal mothers. Concubines offered the advantage of having no ties to Ottoman families who might challenge the dynasty’s dominance.

Roxelana had the good fortune to be chosen within a few months of Suleyman’s enthronement in September 1520 as the empire’s tenth sultan. He was twenty-six; she was seventeen or so. Suleyman had had other concubines before his accession, but Roxelana was the first partner of his long reign, and she succeeded in keeping herself the only one.

ROXELANA WAS A survivor. It was no small achievement that the young girl overcame the violence of her capture. She persevered through the perilous trek from her homeland to the distant Ottoman capital, where she embarked on the bewildering next phase of her life. The Ottoman name chosen for her suggests that she managed to put a congenial face on her fate. Roxelana’s aptitude for survival would soon lift her above the common servitude that was the destiny of most female slaves. She rapidly became adept at reading the political and sexual dynamics of the imperial harem—that private world of the sultan’s female relatives, concubines, children, and their many attendants. It was Roxelana’s charm combined with her savvy that enabled her to best the competition within the harem and to achieve the hitherto unknown roles of favorite and then wife and queen.

Portrait of the young Roxelana, titled “Roxelana, wife of Suleyman.” Venetian School, sixteenth–seventeenth century.

Roxelana and Suleyman shattered tradition by creating a nuclear family in a polygynous world. Until then, royal concubines had a single, well-defined responsibility. Once a concubine bore a male child to an Ottoman prince or sultan, her sole duty was to work toward the boy’s future political success. No conflict would arise here because the birth of a son terminated his mother’s sexual connection with her master. It did not matter if their relationship was one of passion, for tradition dictated that she bear him no more children. He would move on to a fresh concubine, while she remained with her son, her duty to raise him and accompany him to whatever provincial post he was assigned as prince.

These reproductive practices made uninhibited or prolonged relationships nearly impossible. Only if a concubine first gave birth to one or more daughters could her master continue to indulge any affection for her, at least until she bore a son. Hollywood stereotypes of lascivious sultans and their bevies of languid, sex-obsessed slaves only rarely held true for the Ottomans. Sex for males of the dynasty was a political duty as much as it was a pleasure. As with all hereditary dynasties, survival depended on the production of talented princes eligible to rule. As for the concubine, she was a sexual being for only a phase of her career but a mother for the rest of her life. Roxelana was both.

Читать дальше