The Old Palace was home to all who lived within it and school to the lucky ones marked for advancement. In this world Roxelana acquired the polish she needed to attract the sultan’s attention. Catch his eye she must, for Suleyman came to the Old Palace only on occasional visits. He lived in and governed from the New Palace.

Surrounded by extensive lawns and gardens and fortified walls, the sprawling pastoral complex of the sultan’s palace occupied the old Byzantine acropolis. The promontory was a majestic setting for the seat of an expanding empire. It commanded the confluence of the city’s three great waters: the Bosphorus, gateway to the Black Sea; the Golden Horn, an estuary whose natural harbor sheltered the imperial shipyards; and the Sea of Marmara, which led through the Aegean to the Mediterranean. From the very edge of Europe, the sultan could gaze upon the shores of Asia.

The New Palace was resolutely a world of men. This royal capital in miniature housed not only the sultan and his large personal suite but also the various offices of government. These included two treasuries (public and royal), bureaucratic offices, and the Divan, the council hall where the most important matters of state were deliberated. The sultan’s own private chambers occupied one corner of the innermost of the palace’s three courtyards. An academy for training the most promising of young male recruits to Ottoman service took up much of the rest. Their quarters formed a perimeter around the tree-and flower-studded lawn that blanketed the courtyard’s interior space. Like the most promising Old Palace trainees, these youths were instructed and disciplined by both resident eunuchs and teachers brought in from outside. The most advanced served the sultan personally and, if fortunate, might subsequently rise to high office, even to become grand vizier.

When sultans visited the Old Palace, they did so to enjoy the company of their senior concubines, to pay their respects to their mothers, and to monitor the progress of their children. Sometimes they neglected their filial duties, or so thought Gulbahar, Suleyman’s great-grandmother. She wrote plaintively to her son Bayezid II, “My fortune, I miss you. Even if you don’t miss me, I miss you.… Come and let me see you. It’s been forty days since I last saw you.” [2] TSMA, E 10292.

Suleyman, by contrast, was a more frequent visitor, at least in the very first years of his reign. No doubt he sought the counsel of his mother Hafsa, whom he had come to rely on during the years of his princely apprenticeship. But at the Old Palace he also sought new women to bed. The Venetian ambassador Marco Minio reported in 1522, two years after Suleyman’s succession, that the young sultan was “very lustful” and went frequently to “the palace of the women.” [3] Alberi, Relazioni , 3:78.

The Venetians avidly tracked the sultan’s love life because knowledge of who was who in royal politics—who was the mother of which prince, for instance—was vital intelligence.

A story repeatedly told by Europeans described the method by which a sultan chose a new concubine: he would stroll down a lineup of females and drop his handkerchief in front of the one he found desirable. This may have happened on occasion, but the tale seems a poor fit with imperial etiquette and the well-crafted dignity of the sultan. It missed the point that a potential concubine needed opportunity to display the fruits of her training as well as her allure. The Old Palace devised suitable opportunities accordingly.

During a sultan’s visit, his mother or a resident sister would organize refreshment and entertainment. These receptions offered him opportunity to survey attractive young women who served fruit-flavored sherbets or offered a music-and-dance interlude. For her part, an aspiring concubine was ready and eager to display grace and accomplishment. The bolder among them perhaps engaged in guarded flirtation. Did Roxelana beguile Suleyman with the laugh or the smile for which she presumably earned her Ottoman name, Hurrem?

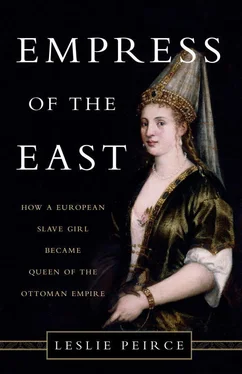

ROXELANA WAS NO raw recruit when she and Suleyman first cast eyes upon one another. Somewhere along the line, between her abduction from Ruthenia and her arrival at the Old Palace, the slave girl must have demonstrated to discerning observers her fitness for more than menial employment. If not directly acquired in Caffa either by a palace agent or a dealer who appraised her as promising material for private resale, she was most likely sold in one of Istanbul’s slave markets.

The principal slave market was located in the commercial heart of the city adjacent to the great Covered Market, which in turn was not very far from the Old Palace. In Roxelana’s day, when the sale of slaves was less centrally controlled, smaller markets could be found in other city districts like the town of Üsküdar on the Asian shore of the Bosphorus. Auctions could be loud affairs as dealers touted their wares. In fact, residents of one Üsküdar village found the din created by brokers and bidders so objectionable that they took court action. [4] Seng, “Fugitives,” 138–139.

For slaves, memory of the market could be indelible, especially as they were liable to physical examination to establish value, with potential concubines subject to a virginity check. The lot of slaves, especially those with aptitude, varied with the socioeconomic status of their male or female buyers. Since slavery among the Ottomans consisted predominantly of household (rather than agricultural) service, slaves’ duties tended to match their owners’ lifestyles. Wealthier households trained slaves in a range of positions—cook, groom, scribe, even entertainer. A slave’s appearance varied accordingly, to the point that a runaway male might go unnoticed because he wore his master’s cast-off clothing. [5] Ibid., 160–162.

“They treated their servants better than we do,” noted Theodore Spandouginos, a Greek of noble descent who knew both Istanbul and Turkish. The reason was that “Mahomet [the Prophet Muhammad] decreed that no one should keep a slave for more than seven years.” [6] Spandouginos, Origins , 224.

In fact, emancipation after a term of service was common, at least among the wealthier Ottomans. It was one factor in their unceasing demand for slave labor. [7] Inalcık, Economic , 284.

Perhaps a speculator in female slaves, most likely a woman, perceived promise in Roxelana and bought her at market. She would wager on turning a smart profit by training and then reselling the girl at a price commensurate with her enhanced value. Perhaps a prominent Istanbul household acquired the Russian girl and soon discovered her to be talented and adaptable. Especially if Roxelana was purchased at some point by a high-ranking government official—or his wife, for rich women had their own money and their own slaves—the opportunity to curry favor by grooming and presenting her to a member of the dynasty would be obvious.

Claims that Roxelana was a gift to Suleyman circulated among both Ottomans and foreign envoys. If that was the case, she likely came to him as a congratulatory offering on the occasion of his accession in September 1520. One account held that a married sister of the new monarch secretly trained the girl and gave her as a present to her mother Hafsa, who in turn introduced the slave to her son. [8] Dernschwam, Diary , 186.

More than one account, however, held that it was Ibrahim, Suleyman’s male favorite, who gave Roxelana to him. [9] Bassano, Costumi , chap. 15.

Originally a fisherman’s son captured from the Adriatic coast, Ibrahim would be raised by Suleyman in 1523 to the highest state office, the grand vizierate. In any event, the young sultan certainly lost no time in bedding his new concubine, for their first child, Mehmed, was born within at most thirteen months of his enthronement.

Читать дальше