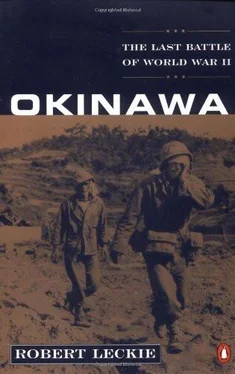

Robert Leckie

OKINAWA

The Last Battle of World War II

To My Fourth Grandson,

Sean Michael Leckie

On September 29, 1944, Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, commander of the Pacific Ocean Area (POA), and Fleet Admiral Ernest King, chief of U.S. Naval Operations, conferred in San Francisco on the next steps to be taken to deliver the final crusher to a staggering Japan. This was the conference’s stated purpose, but the unspoken objective was to persuade the irascible, often-inflexible King to accept Nimitz’s battle plan, instead of King’s own.

This would not be easy, for the tall, lean, hard, humorless King was known to be “so tough he shaves with a blowtorch.” Indeed, his civilian chief, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox, had ordered from Tiffany’s a silver miniature blowtorch with that inscription on it. Thus, there was some trepidation among Nimitz and his Army chiefs—Lieutenant General Simon Bolivar Buckner of Army Ground Forces (POA) and Lieutenant General Millard Harmon of the newly formed Army Air Forces (POA)—as well as Admiral Raymond Spruance, alternate chief with Fleet Admiral William “Bull” Halsey, of Nimitz’s battle fleet. [1] When Spruance commanded this enormous concentration of naval striking power, it was called “Task Force Fifty-eight”; when Bull Halsey’s flag was flown it was “Task Force Thirty-eight.”

They knew that King was convinced the next operation in the Pacific should be landings on the big island of Formosa off the Chinese southeastern coast. If Nimitz and staff could persuade King to accept General of the Armies Douglas MacArthur’s plan to invade Luzon in the Philippines rather than Formosa, the conference would end in a rare and high note of interservice cooperation.

Each of the conferees was assigned a luxurious suite in the elegant Saint Francis Hotel, assembling in Admiral King’s opulent quarters for three days of discussions. Here they were served epicurean meals that were not often to be found on the menu in the Saint Francis dining rooms (wartime rationing then being in effect). Here also—and sometimes in the plainer Sea Frontier headquarters, where maps and logistic tables were more readily available—Nimitz presented his chief with one of those carefully drawn memoranda for which he was justly celebrated. With an outward calm and precision that did not reflect his inner apprehension, the pink-cheeked, white-haired, baby-faced Nimitz was careful not to provoke the stern-faced, short-fused Admiral “Adamant” while he explained exactly why King’s cherished invasion of Formosa would be impossible to mount at that time.

First, defending that huge island now known as Taiwan, the Japanese had a full field army much too strong to be attacked by American forces then available in the Pacific, a point vigorously supported by both Buckner and Harmon.

Second, the casualty estimate, based upon U.S. losses of 17,000 dead and wounded while eliminating 32,000 dug-in Japanese on the island of Saipan, would reach at least 150,000 or more, a slaughter that POA’s resources could not bear and the American public would never supinely accept. Conversely, MacArthur—always ready and happy to predict minimal losses in any of his own operations—had estimated Luzon could be taken with comparatively moderate casualties.

Throughout this recital Ernest King’s face remained stony. It is possible—though not reported anywhere—that at the introduction of the name of Douglas MacArthur, one of the admiral’s eyelids might have flickered. But Nimitz was prepared for this moment, for he had long ago learned that you cannot take without giving, and Nimitz would give with an alternative to King’s cherished plan. He suggested to his chief that if he acquiesced in MacArthur’s liberation of Luzon and recapture of Manila, these victories would clear the Pacific for the direct invasion of Japan’s home islands by seizing Iwo Jima and Okinawa and using them as staging areas. King’s eyebrows rose as Nimitz continued: this would completely sever Japan from her oil sources in Borneo, Sumatra, and Burma, and without this lifeblood of war her fleets could not sail, her airplanes fly, her vehicles roll, or her industries produce. Equally satisfying, from Okinawa and Iwo the giant B-29s or Superforts could intensify their bombardment of Japan proper and might conceivably even bomb Nippon into submission without the necessity of invading her home islands.

Admiral King listened intently to Nimitz’s recital, shooting out tough, incisive questions. He admitted that he had read a Joint Chiefs’ report questioning the feasibility of a Formosa invasion, although he did wonder openly about the wisdom of hitting Iwo only 760 miles from Japan and within the Prefecture of Tokyo itself. Turning to Admiral Spruance, who three months earlier had informed the Navy chief that he favored attacking Okinawa, he asked: “Haven’t you something to say? I thought that Okinawa was your baby.” Never a man to allow himself to be caught between the upper and nether millstones of command, Spruance replied that he thought his direct superior—Nimitz—had summarized the situation nicely, and he had nothing to add.

To the Nimitz team’s gratified surprise, Admiral Adamant graciously agreed to substitute Iwo and Okinawa for his cherished Formosa plan, even though that meant he must put his eagerness to help China on hold. It might have been that Nimitz’s proposal was attractive to him because it delayed the politically explosive question of who would be the Supreme Allied Commander in the Pacific: Nimitz or MacArthur? For years Douglas MacArthur had actively sought that eminence, almost insanely jealous as he was of the title Supreme Allied Commander, European Theater, held by his “former clerk,” Dwight Eisenhower. To that end he had cultivated the support of powerful politicians and the conservative stateside press, desisting only when an exasperated Franklin Delano Roosevelt informed him that if the Pacific were to have a Supreme Commander, it would be Nimitz. This way, King may have reasoned, his decision—bound to be popular with neither side in the abrasive Army-Navy rivalry of World War II—could be delayed until the actual invasion of Japan, if there were such an operation, for both Nimitz and King dreaded the fearful carnage, both American and Japanese, that might occur if it were attempted. As sailors they understood perhaps better than the always-optimistic soldier MacArthur the terrible consequences if such a gigantic amphibious operation were to fail.

So the conference in San Francisco ended on a happy note, with King returning to Washington to report his approval to his comrades on the Joint Chiefs, and Nimitz with his flag officers going back to Hawaii to plan for the new operations and especially for Iwo and Iceberg , the code name for Okinawa.

Okinawa lies at the midpoint of the Ryukyu Islands [2] Because there is no hard-and-fast rule for translating Japanese geographical terms— shoto , meaning various islands or group of islands; gunto or retto, a group of islands; shima or jima, an island; or ie, an islet—this narrative will use the general English words for the same.

and almost between Formosa (Taiwan), 500 nautical miles to the southwest, and Kyushu, 375 miles to the north.

In ancient times Okinawa was a dependency of China, paying an annual tribute to the Imperial Court at Peking. The group of islands was called Liu-chi’u , the Chinese word usually pronounced “Loo Choo,” meaning either “pendant ball” or “bubbles floating on water”; but after annexation by Japan in 1879, their new lords, who have great difficulty pronouncing the “L” sound, changed their name to Ryukyu.

Читать дальше