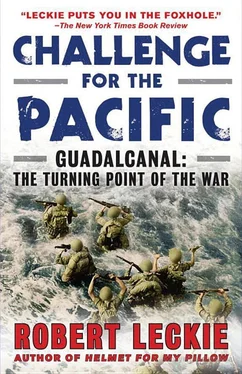

Robert Leckie

CHALLENGE FOR THE PACIFIC

Guadalcanal: The turning Point of the War

To Bud Conley, Lew Juergens, and Bill Smith,

my buddies on Guadalcanal

Praise for CHALLENGE FOR THE PACIFIC

“[Leckie] has succeeded in compressing numerous tales into a readable story, but his greatest contribution is a unique feeling for combat.… His marines are living, brawling, obscene, blasphemous—and utterly believable. He has caught their gallows humor, their cockiness and their savagery in the business of battle.”

—JOHN TOLAND,

The New York Times Book Review

“A stirring story of America’s survival in its grimmest hour… as readable and gripping as a novel.”

—

The Patriot Ledger (Massachusetts)

“Here is a book to wrench the heart. It is a driving, relentless narrative that summons up all of the hideous color and clamor of battle. But, more than that, it is a timely evocation of what a nation must do in wars to preserve its freedom.… [This] book is a splendid weld of the strategies, views and experiences of soldiers, sailors and airmen.”

—

Newark News

“Leckie is a brilliant war writer.”

—New Orleans

Times-Picayune

“[A] true winner… Excitement, action, fast narrative pace, and a deep respect for the rudiments of genuine patriotism mark the story.… [Leckie] presents the Allies and the Japanese as separate people, giving them the stature of human beings involved in desperate battle.”

—

Nashville Banner

“Despite its scope, the story is told in individual terms—Japanese and American. Characters are very much alive on the printed page. Challenge for the Pacific is fast-paced and informative.”

—

Navy Times

“An exceedingly good account of a feat of arms which remains unsurpassed… enthralling.”

—

The Times Literary Supplement

“[An] epic tale ably told… To those who were there this book will bring back vivid memories… To those who were not there this book should bring some small realization of what it was like.”

—

El Paso Times

“Detailed and dramatic… In these pages one can feel the frustration, despair and confusion experienced by both sides in the savage see-saw struggle.”

—

Tulsa World

“Leckie puts flesh on the bones of history.… The book has the ring of authenticity.… It is intensely dramatic, vivid, broad, and yet intimate in detail, deeply moving in its portrayal of the human side of war. In the best sense, it is history made alive.”

—

Pasadena Star-News

“A vivid portrayal… worthy of attention.”

—

Buffalo Courier-Express

“Challenge for the Pacific is more than the battle of Guadalcanal. It is the living and dying of Americans and Japanese.… [Leckie] knows how a ground-pounding Marine thinks, talks and reacts.”

—

Leatherneck magazine

“Leckie describes this outstanding American combined operation from an intensely personal yet well-documented angle.”

—

The Daily Telegraph

ON AUGUST 7, 1962—the twentieth anniversary of the landings at Guadalcanal—men of the First Marine Division Association received a message from Sergeant Major Vouza of the British Solomon Islands Police. Vouza said: “Tell them I love them all. Me old man now, and me no look good no more. But me never forget.”

Neither would anyone else who had been on Guadalcanal, not the Japanese who tortured Vouza, and from whom this proud and fierce Solomon Islander exacted a fearsome vengeance, not the Americans who ultimately conquered. For Guadalcanal, as the historian Samuel Eliot Morison has said, is not a name but an emotion. It is a word evocative, even, of sense perception; of the putrescent reek of the jungle, the sharp ache of hunger or the pulpy feel of waterlogged flesh, as well as of all those clanging, bellowing, stuttering battles—land, sea, and air—which were fought, night and day, to determine whether America or Japan would possess a ramshackle airfield set in the middle of 2500 square miles of malarial wilderness.

More important, historically, Guadalcanal was the place at which the tide in the Pacific War turned against Japan. Although this distinction has often been conferred upon Midway, the fact remains that the naval air battles fought at Midway did not turn the tide, but rather gave the first check to Japanese expansion while restoring, through the loss of four big Japanese aircraft carriers as against only one American, parity in carrier power.

After Midway the Japanese were still on the offensive. They thought that way and they acted that way. “After Coral Sea and Midway, I still had hope,” said Captain Toshikazu Ohmae, operations officer for the Japanese Eighth Fleet, “but after Guadalcanal I felt that we could not win.” Rear Admiral Raizo Tanaka, commander of the Guadalcanal Reinforcement Force, goes even further, declaring: “There is no question that Japan’s doom was sealed with the closing of the struggle for Guadalcanal.” Captain Tameichi Hara, a destroyer commander who fought under Tanaka at both Midway and Guadalcanal, shares his chief’s opinion, writing: “What really spelled the downfall of the Imperial Navy, in my estimation, was the series of strategic and tactical blunders by (Admiral) Yamamoto after Midway, the Operations that started with the American landing at Guadalcanal in early August, 1942.” And from the Japanese Army, as represented by Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi, commander of Japan’s first major attempt to recapture the island, comes this categorical statement: “Guadalcanal is no longer merely a name of an island in Japanese military history. It is the name of the graveyard of the Japanese Army.”

Guadalcanal was also the graveyard for Japan’s air force. Upwards of 800 aircraft, with 2362 of her finest pilots and crewmen, were lost there. Perhaps even more important, the habit of victory deserted the heretofore invincible Japanese pilots there, and before the battle was over Japanese carrier power ceased to be a factor in the Pacific until, nearly two years later, the invasion of Saipan lured it to its effective destruction. Japanese naval losses were also high. Even though Japan’s loss of 24 warships totaling 134,389 tons was hardly greater than the American loss of 24 warships totaling 126,240 tons, Japan could not come close to matching the American replacement capacity. Finally, the total American dead was, at the utmost, only about one tenth of the Japanese probable total of fifty thousand men.

However, neither comparative statistics nor the number of men and arms engaged can measure a battle’s importance in history. Only a few hundred fell when Joan of Arc raised the siege of Orléans and changed the course of events in the west, while Marathon, Valmy, Saratoga and Waterloo—to name a few other decisive battles—would not, in combined casualties, equal the number of those whose blood stained one of Genghis Khan’s forgotten battlefields. A battle is only great because after it has been fought things are never the same. The war has been changed in its direction, its mood, its attitudes, its men, and sometimes its very tactics. Finally, in changing a war, a great battle alters the course of world events.

This condition and its corollaries are fulfilled by Guadalcanal. After Guadalcanal the Pacific War that had been moving south toward Australasia-Fijis-Samoa turned north toward Japan, and the United States, having been starved for victory, never again tasted defeat. More simply, after Guadalcanal the Americans were on the offensive and the Japanese were on the defensive.

Читать дальше