It was at Guadalcanal that such myths as the invincibility of the Japanese soldier or Zero fighter-plane were destroyed, that such devices as radar-controlled naval gunfire were introduced, and that such reputations as those of Chuichi Nagumo, the hero of Pearl Harbor, or the idolized Isoroku Yamamoto were either ruined or tarnished while those of such Americans as Halsey, Kinkaid, and Richmond Kelly Turner among the admirals, Alexander Patch and Lightning Joe Collins among the Army generals, and Archer Vandegrift and Roy Geiger among the Marines, were being made. From Guadalcanal came the tactics—land, sea, and air—which were to become American battle doctrine throughout World War II, and out of this struggle emerged the seasoned young leaders who were to command the ships and regiments and squadrons which were to strike the Axis enemy everywhere.

Guadalcanal wrecked Japan’s grand strategy. Imperial General Headquarters had deliberately hurled the surprise attack at Pearl Harbor to prevent the United States Navy from interfering with the Japanese timetable of conquest in the Pacific. By the time America had recovered from Pearl Harbor, it was believed, Japan would have built a chain of impregnable island forts around her stolen empire.

America, tiring of a costly and bloody war, would then be willing to negotiate a peace favorable to Japan. But Guadalcanal shattered this dream. There, barely a year after Pearl Harbor, the Americans stood in triumph with their faces turned toward Japan.

And once it was clear that Guadalcanal was lost, the sober heads at Imperial General Headquarters knew that all was lost. The countries of Southeast Asia, the lush, rich islands of the Southern Seas—all of these “lands of everlasting summer”—were to be taken away from them.

After Guadalcanal, as the Japanese knew in their despair, as the Americans realized with rising jubilation, the Pacific War could never be the same.

ROBERT LECKIE

Mountain Lakes, New Jersey

September 10, 1964

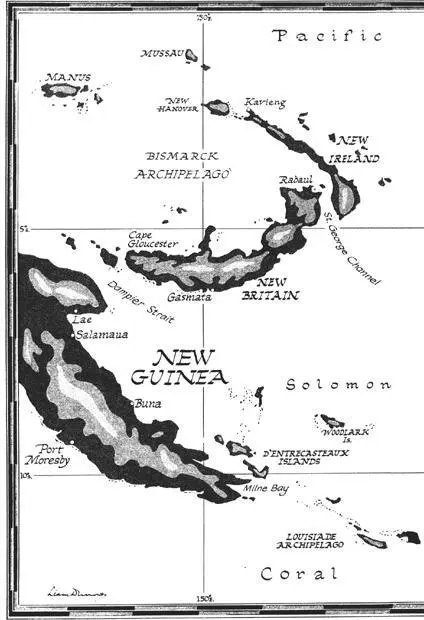

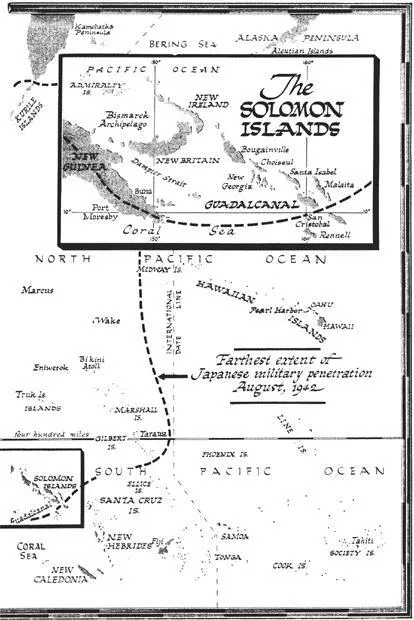

Area of Action in the Solomons

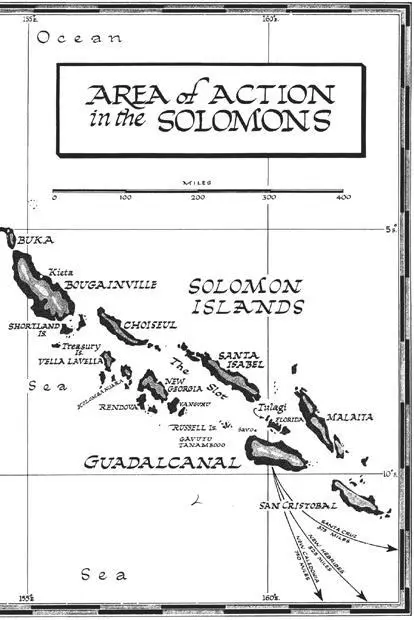

The Pacific Ocean with Insert of Area of Action

Guadalcanal

Battle of the Tenaru

Battle of Bloody Ridge

Battle of Henderson Field

Matanikau Action

PART ONE

The Challenge

THE ADMIRAL was tall, hard, and humorless. His face was of flint and his will was of adamant. In the United States Navy which he commanded it was sometimes said, “He’s so tough he shaves with a blowtorch.” President Roosevelt was fond of repeating this quip in the admiral’s presence, hoping to produce, if there had been no reports of fresh disaster in the past twenty-four hours, that fleeting cold spasm of mirth—like an iceberg tick—which the President, the Prime Minister of England, and the admiral’s colleagues on the Anglo-American Combined Chiefs of Staff were able to identify as a smile.

If levity was rare in Admiral Ernest King, self-doubts or delusions were nonexistent. He was aware that he was respected rather than beloved by the Navy, and he knew that he was hated by roughly half of the chiefs of the Anglo-American alliance. Mr. Stimson, the U.S. Secretary of War, hated him; so did Winston Churchill and Field-Marshal Sir Alan Brooke and Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham. 1Nevertheless, Admiral King continued to express the wish that was anathema in the ears of these men, as it was also irritating or at least unwelcome in the ears of General George Marshall, the U.S. Army Chief of Staff, and General H. H. Arnold, chief of the Army Air Force.

Admiral King wanted Japan checked.

He wanted this even though he was bound to adhere to the grand strategy approved by Roosevelt and Churchill: concentrate on Hitler first while containing the Japanese.

But what was containment?

Containing the Japanese during the three months beginning with Pearl Harbor had been as easy as cornering a tornado. The Japanese had crippled the U.S. Pacific Fleet and all but driven Britain from the Indian Ocean by sinking Prince of Wales and Repulse . Except for scattered American carrier strikes against the Gilberts and Marshalls the vast Pacific from Formosa to Hawaii was in danger of becoming a Japanese lake. Wake had fallen; Guam as well; the Philippines were on their way. Japan’s “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” had already absorbed the Dutch East Indies with all their vast and precious deposits of oil and minerals, it had supplanted the French in Indochina and evicted the British from Singapore. Burma, Malaya, and Thailand were also Japanese. The unbreachable Malay Barrier had been broken almost as easily as the invincible Maginot Line had been turned. Japan now looked west toward India with her hundreds of millions; and if Rommel should beat the British in North Africa, a German-Japanese juncture in the Middle East would become a dreadful probability. Meanwhile, great China was cut off and Australia—to which General Douglas MacArthur had been ordered should he succeed in escaping from Corregidor—was threatened by a Japanese invasion of New Guinea. At that moment in early March, as Admiral King knew, the necessary invasion force was being gathered at Rabaul, the bastion which the Japanese were building on the eastern tip of New Britain.

All this—all this ferocious speed and precision, all this lightning conquest, this sweeping of the seas and seizure of the skies—all this was containment?

Admiral King did not think so. He thought it was rather creeping catastrophe. He thought that the Japanese, unchecked, would reach out again. They would try to cut off Australia, drive deeper eastward toward Hawaii; and build an island barrier behind which they could drain off the resources of their huge new stolen empire. It was because King feared this eventuality that he had, as early as January 1942, when the drum roll of Japanese victories was beating loudest, moved to put a garrison of American troops on Fiji. Already forging an island chain to Australia, he was still not satisfied: in mid-February he wrote to General Marshall urging that it was essential to occupy additional islands “as rapidly as possible.” The Chief of Staff did not reply for some time. When he did, he asked what King’s purpose might be. The Navy Commander-in-Chief, Cominch as he was called, answered that he hoped to build a series of strong-points from which a “step-by-step” advance might be made through the Solomon Islands against Rabaul.

That was on March 2. Three days later, Admiral King addressed a memorandum to President Roosevelt. He outlined his plan of operations against the Japanese. He summarized them in three phrases:

• Hold Hawaii.

• Support Australasia.

• Drive northwestward from New Hebrides.

Admiral Ernest King was not then aware of it, but he had at that moment put a tentative finger on an island named Guadalcanal.

Japan was preparing to reach out again.

At Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo the faces of the planners were bright with victory fever. 2Who could blame them, really? Who else might bask so long in such a sun of success without becoming slightly giddy? Of course, some of the officers of the Naval General Staff had passed from fever into delirium. Some of them—conscious that it was the Navy which had brought off the great stroke at Pearl Harbor, which had played the greater role in the other victories, which had shot the enemy aviators from the skies—some of them were proposing that Australia be invaded.

Читать дальше