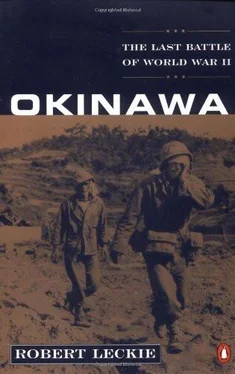

Meanwhile the huge Japanese merchant fleet, employed in carrying vital oil and valuable minerals to the headquarters of an empire singularly devoid of natural resources, had been steadily blasted into extinction by the flashing torpedoes of the United States Navy’s submarines. Here indeed were the unsung heroes of the splendid Pacific sea charge of three years’ duration: four thousand miles from Pearl Harbor to the reef-rimmed slender long island of Okinawa. These men of “the silent service,” as it was called, were fond of joking about how they had divided the Pacific between the enemy and themselves, conferring on Japan “the bottom half.” In fact it was true. Only an occasional supply ship or transport arrived at or departed Nippon’s numerous sea-ports, themselves silent, ghostly shambles. Incredibly, the American submarines, now out of sea targets, had penetrated Japan’s inland seas to begin the systematic destruction of its ferry traffic. Transportation on the four Home Islands of Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu, and Hokkaido was at a standstill. Little was moved: by road or rail, over the water or through the air. In the Imperial Palace hissing, bowing members of the household staff kept from Emperor Hirohito the shocking, grisly protests arriving in the daily mail: the index fingers of Japanese fathers who had lost too many sons to “the red-haired barbarians.” Most of these doubters—silent and anonymous because they feared a visit from the War Lords’ dreaded Thought Police—were men who had lived and worked in America, knowing it for the unrivaled industrial giant that it was. They did not share the general jubilation when “the emperor’s glorious young eagles” arrived home from Pearl Harbor. Their hearts were filled with trepidation, with secret dread for the retribution that they knew would overtake their beloved country.

For eight months following Pearl Harbor, the victory fever had raged unchecked in Japan. During that time the striking power of America’s Pacific Fleet had rolled with the tide on the floor of Battleship Row. Wake had fallen, Guam, the Philippines. The Rising Sun flew above the Dutch East Indies, it surmounted the French tricolor in Indochina, blotting out the Union Jack in Singapore, where columns of short tan men in mushroom helmets double-timed through silent streets. Burma and Malaya were also Japanese. India’s hundreds of millions were imperiled, great China was all but isolated from the world, Australia looked fearfully north to Japanese bases on New Guinea, toward the long double chain of the Solomon Islands drawn like two knives across its lifeline to America. But then, on August 7, 1942—exactly eight months after Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagomo had turned his aircraft carriers into the wind off Pearl Harbor—the American Marines landed on Guadalcanal and the counter-offensive had begun.

In Japan the war dance turned gradually into a dirge while doleful drums beat a requiem of retreat and defeat. Smiling Japanese mothers no longer strolled along the streets of Japanese towns and cities, grasping their “belts of a thousand stitches,” entreating passersby to sew a stitch into these magical charms to be worn into battle by their soldier sons. For now those youths lay buried on faraway islands where admirals and generals—like the Melanesian or Micronesian natives whom they despised—es—caped starvation by cultivating their own vegetable gardens of yams and sweet potatoes. And the belts that had failed to preserve the lives of the boys who wore them became battle souvenirs second only to the Samurai sabers of their fallen officers.

This, then, was the Japan that the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff still considered a formidable foe, so much so that it could be subdued only by an invasion force of a million men and thousands of ships, airplanes, and tanks. To achieve final victory, Okinawa was to be seized as a forward base for this enormous invading armada. In the fall of 1945 a three-pronged amphibious assault called Operation Olympic was to be mounted against southern Kyushu by the Sixth U.S. Army consisting of ten infantry divisions and three spearheading Marine divisions. This was to be followed in the spring of 1946 by Operation Coronet, a massive seaborne assault on the Tokyo Plain by the Eighth and Tenth Armies, spearheaded by another amphibious force of three Marine divisions and with the First Army transshipped from Europe to form a ten-division reserve. The entire operation would be under the command of General of the Armies MacArthur and Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz.

Okinawa would be the catapult from which this mightiest amphibious assault force ever assembled would be hurled.

The Divine Wind

CHAPTER THREE

Japanese Imperial Headquarters, still refusing to believe that Nippon was beaten, still writing reports while wearing rose-colored glasses, also anticipated an inevitable and bloody fight for Okinawa as the prelude to a titanic struggle for Japan itself. While the American Joint Chiefs regarded Operation Iceberg as one more stepping-stone toward Japan, their enemy saw it as the anvil on which the hammer blows of a still-invincible Japan would destroy the American fleet.

Destruction of American sea power remained the chief objective of Japanese military policy. Sea power had brought the Americans through the island barriers that Imperial Headquarters had thought to be impenetrable, had landed them at Iwo within the very Prefecture of Tokyo, and now threatened to provide them a lodgment 385 miles closer to the Home Islands. Only sea power could make possible the invasion of Japan, something that had not happened in three thousand years of Japan’s recorded history—something that had been attempted only twice before.

In 1274 and 1281 Kublai Khan, grandson of the great Genghis Khan and Mongol emperor of China, massed huge invasion fleets on the Chinese coast for that purpose. Japan was unprepared to repel such stupendous armadas, but a kamikaze, or “Divine Wind”—actually a typhoon—struck both Mongol fleets, scattering and sinking them.

In early 1945, nearly seven centuries later, an entire host of Divine Winds came howling out of Nippon. They were the suicide bombers of the Special Attack Forces, the new kamikaze who had been so named because it was seriously believed that they too would destroy another invasion fleet.

They were the conception of Vice Admiral Takejiro Onishi. He had led a carrier group during the Battle of the Philippine Sea. After that Japanese aerial disaster known to the Americans as “the Marianas Turkey Shoot,” Onishi had gone to Fleet Admiral Soemu Toyoda, commander of Japan’s Combined Fleet, with the proposal to organize a group of flyers who would crash-dive loaded bombers onto the decks of American warships. Toyoda agreed. Like most Japanese he found the concept of suicide—so popular in Japan as a means of atonement for failure of any kind—a glorious method of defending the homeland. So Toyoda sent Onishi to the Philippines, where he began organizing kamikaze on a local and volunteer basis. Then came the American seizure of the Palaus and the Filipino invasion.

On October 15, 1944, Rear Admiral Masafumi Arima—the first kamikaze —tried to crash-dive the American carrier Franklin. He was shot down by Navy fighters, but Japanese Imperial Headquarters told the nation that he had succeeded in hitting the carrier—which he had not done—and thus “lit the fuse of the ardent wishes of his men.”

The first organized attacks of the kamikaze came on October 25, at the beginning of the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Suicide bombers struck blows strong enough to startle the Americans and make them aware of a new weapon in the field against them, but not savage enough to shatter them. Too many kamikaze missed their targets and crashed harmlessly into the ocean, too many lost their way either arriving or returning, and too many were shot down. Of 650 suiciders sent to the Philippines, only about a quarter of them scored hits—and almost exclusively on small ships without the firepower to defend themselves like the cruisers, battleships, and aircraft carriers. But Imperial Headquarters, still keeping the national mind carefully empty of news of failure, announced hits of almost 100 percent. Imperial Headquarters did not believe its own propaganda, of course. Its generals and admirals privately guessed hits ranging from 12 to 50 percent, but they also assumed that nothing but battleships and carriers had been hit.

Читать дальше