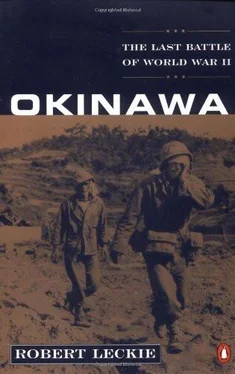

Colonel Clarence Wallace sent the Eighth Marines in at Kunishi Ridge. They were to attack in columns of battalions to seize a road, to split the enemy in two, to carry out General del Valle’s plans for a decisive thrust to the sea. Lieutenant General Buckner joined Colonel Wallace on Mezado Ridge at noon. He watched the Marines for about an hour. They moved swiftly on their objective. Buckner said:

“Things are going so well here, I think I’ll move on to another unit.”

Five Japanese shells struck Mezado Ridge. They exploded and filled the air with flying coral. A shard pierced General Buckner’s chest and he died within ten minutes—knowing, at least, that his Tenth Army was winning.

Command went to Roy Geiger, senior officer and about to be promoted to lieutenant general. The grizzled white bear who had been at Guadalcanal in the beginning was leading at the end on Okinawa.

That came three days later.

On June 21 a patrol from the Sixth Marine Division reached a small mound atop a spiky coral cliff. It was the tip of Ara Point. Beneath them were the mingling waters of the Pacific Ocean and the East China Sea.

A few more days of skirmishing and a reverse mop-up drive to the north remained. When these were over, and the last of the kamikaze had been shot down, the Japanese Thirty-second Army was no more, with roughly 100,000 dead, and, surprisingly, another 10,000 captured. American casualties totaled 49,151, with Marine losses at 2,938 dead or missing and 13,708 wounded; the Army’s at 4,675 and 18,099; and the Navy’s at 4,907 and 4,824. There was little left of Japanese airpower after losses of about 3,000 planes [8] Official and early American estimates of 7,800 Japanese planes lost during the Okinawa Campaign—either in combat or under enemy air raids—were much too high. A more conservative and probably more accurate figure of 3,000 was later made by the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey.

—about 1,900 of them kamikaze —against 763 for the Americans; and the sinking of Yamato and 15 other ships meant the end of Nippon’s Navy. Though the United States Navy had been staggered with 36 ships sunk and another 368 damaged, there were still plenty left to mount the fall invasion of Kyushu from Okinawa.

So the Great Loo Choo fell to the Americans after eighty-three days of fighting. A few hours after the Marine patrol reached Ara Point, Major General Geiger declared organized resistance to be at an end.

A Samurai Farewell

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

On the night of June 21—the day General Geiger declared the American victory on Okinawa—Ushijima and Cho realized in their headquarters under Hill 95 near the Pacific Ocean that the end had come. Soldiers of Colonel John Finn’s Thirty-second Infantry of the Seventh Division were still dropping hand grenades through a vertical air shaft from the top of the hill. The explosives had already killed or wounded ten officers. Neither Ushijima nor Cho wished to meet a similar fate at the hands of the American devils. They would take their own lives in the accepted Samurai ceremony.

Colonel Yahara had desired to join them in hara-kiri, but Ushijima had decreed that his planning officer, with his excellent memory and habit of straightforward reporting, should be the only man to attempt to escape to Tokyo with a full account of what had happened on Okinawa. Unfortunately, in his physique and bearing, Hiromichi Yahara was also the worst possible choice. No matter how he sought to disguise himself, this tall and patrician officer would stand out among the diminutive Okinawan population like a green tree in a petrified forest—and he was quickly captured. Being a Samurai, he had probably asked for a bayonet with which to make the act of expiation like so many other captured Samurai before him. If he had, he certainly would have been laughingly refused.

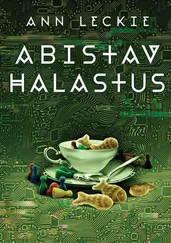

That night under Hill 95 Lieutenant Generals Ushijima and Cho, together with their ranking officers, consumed a farewell dinner prepared for them by the commander’s cook, Tetsuo Nakamuta. It began with bean-curd soup, and then proceeded to a bountiful repast of rice, canned meats, potatoes, fried fish cakes, fresh cabbage, and a dessert of canned pineapple. Sake flowed as freely as the lively conversation. At the meal’s end Isamo Cho produced from his large stock of liquors a bottle of Black and White scotch, with which he and his chief solemnly toasted each other. It was agreed that nothing should be allowed to interfere with the ritual suicide of Ushijima and Cho.

Thus, in the early morning hours just before moonrise, the officers and men of Thirty-second Army Headquarters would deliver the last Banzai of World War II: a climbing charge up Hill 95, and after that, if there were any survivors, the town of Mabuni.

At about 3 A.M. of June 22, 1945, with a glowing white moon polishing the gleaming black waters of the Pacific—and with Ushijima’s staff singing “Umi.Yukaba”— the members of the last Banzai began climbing the cliff.

Behind them at his desk Ushijima wrote his last message to Tokyo: “Our strategy, tactics and techniques all were used to the utmost. We fought valiantly, but it was as nothing before the material strength of the enemy.” Cho wrote: “22nd day, 6th month, 20th year of the Showa Era. I depart without regret, fear, shame or obligations. Army Chief of Staff Cho; Army Lieutenant General Cho, Isamu, age of departure 52 years. At this time and place I hereby certify the foregoing.”

Bowing to his chief, Cho said: “Well, Commanding General Ushijima, as the way may be dark, I, Cho, will lead the way.”

Returning the bow, Ushijima replied: “Please do so, I will take along my fan since it is getting warm.”

An hour later Ushijima and Cho stepped through a fissure in the cliff face overlooking the ocean. [9] This account of Ushijima and Cho’s final moments came from Ushijima’s cook Tetsuo Nakamuta, who was a witness.

It was about six feet high and six feet wide, opening upon a small ledge above the water. Both wore their dress uniforms, complete with medals and saber. A white quilt and a white sheet symbolizing death were laid over the ledge. Above them the moon had begun its descent.

They strolled out to the ledge, Ushijima calmly fanning himself. They bowed in reverence to the eastern sky, the customary obeisance to the emperor, and sat together on the white sheet and quilt. Only a hundred feet behind them were the approaching American soldiers. Having heard voices, they began hurling grenades, unaware that the Japanese generals were so close to them.

First Ushijima and then Cho bared their bellies to the upward thrust of the ceremonial knives in their hands. Upon the sight of blood the adjutant standing by with unsheathed saber delivered the coup de grace.

Two shouts, two saber flashes—and it was done. And the moon began sinking into an obsidian sea.

Epilogue: The Value of Okinawa

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

Truth trying to overtake falsehood is like the sound of an explosion seeking to catch up with the flash, and this seems to be especially true of that greatest myth of World War II: the belief that the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in early August 1945 compelled Japan to surrender.

There is no question that these dreadful fireballs ushering in the Age of the Mushroom Cloud had much to do with Emperor Hirohito’s decision to order his Imperial Conference to accept the Allied surrender offer. But before they were dropped—as has been suggested at the beginning of this narrative—Japan was already a defeated and demoralized nation, deeply divided between the diehards fiercely determined to continue the conflict regardless of the costs, and those timid members of the peace party who realized that the end had come but who still feared to risk the wrath of the firebrands. The atomic bombings, then, brought Hirohito to their side and encouraged them to defy the War Lords. But the fact remains that before then, before Okinawa, Japan was already beaten.

Читать дальше