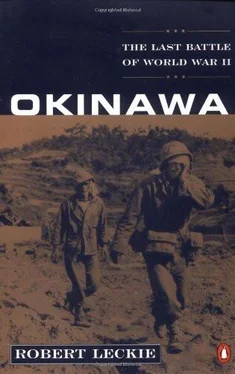

In ten days between May 11 and 21 both sides had been locked in the fiercest fighting of this terrible Okinawa campaign, so hideously reminiscent of the trench warfare of World War I, both in its horrible human losses and the attempt of one side to pierce the defenses of an enemy determined to yield not an inch. It was the unstoppable force against the immovable object; more clearly in military terms, what always happens when firepower wielded by the valiant cannot fail to overwhelm spiritual power alone—no matter how valorous and dedicated its devotees. Casualties in the Seventy-seventh Division were 239 killed, 1,212 wounded, and 16 missing; in the Ninety-sixth Division 138 killed, 1,059 wounded, and 9 missing. Japanese losses are not known, although they were probably twice this number, even though Ushijima’s soldiers were on the defensive.

Perhaps the greatest tribute to the American fighting men on Okinawa came from their favorite English-language broadcaster, Radio Tokyo:

Sugar Loaf Hill… Chocolate Drop … Strawberry Hill. Gee, these places sound wonderful! You can just see the candy houses with the white picket fences around them and the candy canes hanging from the trees, their red and white stripes glistening in the sun. But the only thing red about these places is the blood of Americans. Yes, sir, these are the names of hills in southern Okinawa where the fighting’s so close that you can get down to bayonets and sometimes your bare fists… I guess it’s natural to idealize the worst places with pretty names to make them seem less awful. Why, Sugar Loaf has changed hands so often it looks like Dante’s Inferno. Yes, sir, Sugar Loaf Hill … Chocolate Drop… Strawberry Hill. They sound good, don’t they? Only those who’ve been there know what they’re really like.

True enough. But only the Yanks who were there really knew the final score.

Ushijima Retreats Again

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

Major General John Hodge saw the lodgment on Conical Hill as an opportunity for a turning movement of Ushijima’s eastern flank. He would use the rested Seventy-seventh Division—“rested” in that, withdrawn from combat, they had only to contend with mud, misery, and malaria—to move along Buckner Bay’s coastal flats without fear of plunging fire from Conical Hill. If the Seventy-seventh could reach and capture Yonabaru, they could wheel west to join the Marine divisions moving around the enemy’s western flank and so trap the Thirty-second Army in a double envelopment.

It was an excellent concept and a distinct possibility, although two factors stood between the idea and its execution: renewed rain and Ushijima’s unwillingness to sit still for destruction.

On the night of May 22, with the Sixth Marine Division across the Asato River and poised to break into Naha, there was another conference under Shuri Castle. Lieutenant General Ushijima had decided to retreat. He could no longer hold his Yonabaru-Shuri-Naha line. He would have to withdraw south of the Yonabaru-Naha valley, abandoning even that fine cross-island road. Where to? Should it be the wild, roadless Chinen Peninsula on the east coast, or southernmost Kiyamu Peninsula? The wrangle began. In the end, the Kiyamu was chosen because of the strength of the Yaeju-Yuza Peaks and the honeycombs of natural and artificial caves that could accommodate the entire Thirty-second Army for its final stand.

The next day Ushijima began reinforcing his flanks again to hold off the Americans while his withdrawal began, but he was too late to prevent the turning of the west flank at Naha. The Sixth Division burst into the city’s ruins and began its reduction.

Ushijima still counter-attacked the Seventh Division on the east flank at Yonabaru, trying to relieve the pressure there, but the Seventh’s valiant Dogfaces held fast.

A nocturnal kamikaze raid hurled at Okinawa shipping to coincide with Ushijima’s land strikes was shattered, with 150 planes shot down in exchange for the loss of the destroyer-transport Bates and one LSM, plus damage to eight other ships.

The most ferocious display of antiaircraft power yet seen in the Pacific broke up a daring airborne attack on Yontan and Kadena Airfields. It was an unusually clear night, and there were thousands of witnesses to this small savage setback that the suicide spirit was able to inflict on the Americans.

Perhaps twenty twin-engined bombers came gliding through a fiery lacework woven by American antiaircraft gunners. Eleven of them fell in flames. The rest, except one, fled.

That solitary Sally bomber skidded on its belly along one of Yontan’s runways. When it stopped, eight of fourteen men of the Japanese First Air Raiding Brigade were dead in their seats, but six of them were alive, tumbling out the door, coming erect, and sprinting for parked planes while hurling heat grenades and phosphorous bombs. They blew up eight airplanes, damaged twenty-six others, destroyed two fuel dumps housing seventy thousand gallons of gasoline, and killed two Marines and wounded eighteen others before they were finally hunted down and killed.

In the morning the Tenth Army was still grinding down toward the heart of Ushijima’s defense in Shuri Castle. Marines of the First Division in Wana Draw began to draw swiftly closer to the city and its heights to their east. They began to notice Japanese sealing off caves and quitting the draw. At noon of May 26 Major General del Valle asked for an aerial reconnaissance over the Yonabaru-Naha valley. He had a hunch the Japanese were pulling back from Shuri, trying to sneak out under cover of a heavy rain.

A spotter plane from the battleship New York reported that the roads behind Shuri were packed. Between three thousand and four thousand Japanese were on the rear march with all their guns, tanks, and trucks. In thirteen minutes, despite rain and bad visibility, the warships of the fleet were on the target. Soon fifty Marine Corsairs were with them, rocketing and strafing, and every Marine artillery piece or mortar within range had its smoking muzzle pointed toward the valley. They killed from five hundred to eight hundred Japanese and littered the muddy roadways with wrecked vehicles.

Three days later the Marines took Shuri Castle.

It was not supposed to be theirs to take; it was the objective of the Seventy-seventh Division, the very plum of the Okinawa fighting, but the First Marine Division took it anyway.

General del Valle sent a battalion of the Fifth Marines climbing into Shuri on May 29. He wanted to get around and behind the Japanese still holding out in Wana Draw. The First Battalion quickly stormed Shuri Ridge to the east, or left, of the draw—so quickly that Lieutenant Colonel Charles Shelburne asked permission to go on to the castle eight hundred yards east. Del Valle granted it. The Seventy-seventh Division was still two days’ hard fighting from the castle, and the chance was too good to ignore. The light defenses around Shuri might be only a temporary lapse.

Company A of the Fifth Marines under Captain Julius Dusenbury began slogging east in knee-deep mud. Inside Captain Dusenbury’s helmet was a flag, as had become almost customary among Marine commanders since the Suribachi flag-raising. While the Marines marched, del Valle was just barely averting the Seventy-seventh’s planned artillery and aerial strike on Shuri Castle, and then Dusenbury’s Marines overran a party of Japanese soldiers and swept into the castle courtyard, into the battered ruins of what had once been a beautiful palace with curving, tiered roofs of tile. They ran up to its high parapet, and over this Captain Dusenbury flew his flag.

Shuri Castle, the key bastion of the Okinawa defenses, was in American hands—and if the Seventy-seventh Division was irritated, if the Tenth Army was displeased, the soldier who commanded the Americans on Okinawa could not be entirely annoyed. The flag that Captain Dusenbury of South Carolina flew was the flag of Simon Bolivar Buckner’s father. The Stars and Bars, not the Stars and Stripes, waved over Okinawa.

Читать дальше