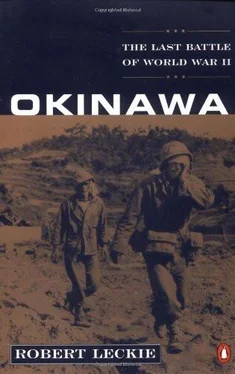

But now—though dimly—the GIs realized that they had come to their own Tarawa, Peleliu, or Iwo Jima with their fortifications of steel, concrete, and coral, interconnected by mazes of tunnels with interlocking fire and all approaches preregistered by every weapon. They now knew—as the Marines in the Central Pacific had learned—that enormous massed bombardment of these truly formidable defenses from sea, air, and land was usually if not always no more effective than a smoke screen. True, they would cause some casualties, but never enough to be decisive; and the accident of a lucky hit could never be repeated on call. Only the impetuous foot soldier slashing in with his hand weapons and using tanks, hurling explosives and aiming flame, can succeed in a war against armed and resolute moles. The naval shell’s flat trajectory, the bomb’s broad parabola, the artillery projectile’s arc—even the loop of the mortar—cannot chase such moles down a tunnel. If they can occasionally collapse the whole position with a direct hit, a rare feat, they have knocked out only one spoke in the enemy’s wheel. But the wheel still turns, killing and maiming, and again in the absence of that military miracle—direct hits on call —the man on foot has to go in. Too often even without his tanks.

Moreover, the losses in armor and the casualties among the American GIs on that near-disastrous April 19 were not only the result of attacks made into Ushijima’s clever and sometimes-invisible defenses spouting death and destruction, but also complicated by the terrain of southern Okinawa itself. It was, as the Army’s official history states: “ground utterly without pattern; it was a confusion of little, mesa-like hilltops, deep draws, rounded clay hills, gentle green valleys, bare and ragged coral ridges, lumpy mounds of earth, narrow ravines and sloping finger ridges extending downward from the hill masses.”

On April 20, General Hodge’s three-division assault into Ushijima’s meat grinder was renewed: Seventh on left, Ninety-sixth in the center, and Twenty-seventh on the right. In these first two formations the GIs, now thoroughly blooded in this type of warfare, moved forward more warily and skillfully. The Thirty-second Infantry of the Seventh, or “Hour Glass,” took Ouki Hill with surprising ease, and then struck at Skyline Ridge, blanketing it with smoke to blind the numerous enemy mortarmen there. The tactic worked, especially after two gallant soldiers—First Lieutenant John Holms and Staff Sergeant James McCarthy—led a final charge to seize the hill, but later perished in a fierce enemy counter-attack that was hurled back. Flamethrowing tanks were of major assistance in this action, burning out a forward mortar position that could have been troublesome.

But the Skyline’s dogged defenders did not submit so tamely. One machine gunner in a pillbox was particularly tenacious until Sergeant Theodore MacDonnell, a mortar observer not expected to join a battle, entered the struggle on his own, charging the pillbox throwing grenades. Next he borrowed a BAR, and when that jammed, a carbine—rushing the enemy position with this ordinarily most useless weapon in the American arsenal. At close range, however, it could do damage, and MacDonnell used it to kill all three gunners. Then, his Celtic blood aroused, he picked up the enemy gun and heaved it down the embankment, followed by a knee mortar. Without pausing to thank MacDonnell for this distinguished favor, one of Colonel Finn’s companies proceeded to clear Skyline at a cost of two killed and eleven wounded. Hill 178 now came under American fire, and after two days patrols blasting enemy caves found these positions stuffed with corpses: two hundred in one, a hundred in another, fifty in a third, and forty-five in a fourth. Those who had survived had been withdrawn.

The 184th Infantry’s objective was the Rocky Crags, two coral pinnacles that had to be taken before towering Hill 178 could be assaulted. But no headway was made the first day. Dismayed, General Arnold came to the front to study these obstacles. Deciding that the crags could be fragmented by direct artillery fire, he ordered a 155 mm howitzer up front. Setting up on a knoll eight hundred yards away and firing over open sights, the crew’s first missile—a ninety-five-pound shell with a hardened tip and a concrete-piercing fuse—sent a hefty chunk of coral flying into the air. Seven more destructive shots so upset the Japanese that they sprayed the knoll with machine-gun fire. Two men were wounded, and the survivors quickly dug a hole for their gun. Now unseen, assisted by other guns and flamethrowing tanks, the Americans literally shot both crags into smithereens until both collapsed on themselves.

To the Seventh’s right the Ninety-sixth struck at three ridges: Tanabaru-Nishibaru-Tombstone. It took two days of savage fighting to clear Tombstone and to advance to the crest of Nishibaru. On the night of April 21-22 the Japanese counter-attacked three times against a battalion of the 382nd commanded by Lieutenant Franklin Hartline. In one charge Staff Sergeant David Dovel lifted his machine gun to fire it at the enemy full-trigger, severely burning his hands on the red-hot barrel. Dovel was also wounded in both legs, but survived. Meanwhile soldiers firing light or 60 mm mortars elevated their small stovepipes to a dangerously close eighty-six degrees, dropping shells only thirty yards to their front. Colonel Hartline joined the battle, throwing grenades and firing the weapons of the fallen. At 3:15 A.M. the Japanese retreated, leaving 198 dead comrades behind.

Tanabaru now lay temporarily open, and it was Captain Hoss Mitchell’s Lardasses who seized the opportunity. Its earlier losses filled by replacements, the company fought a savage hand-grenade battle that lasted nearly four hours, until Mitchell with three grenades and a carbine rushed the crest to wipe out a machine-gun nest. By nightfall of April 23 the Ninety-sixth held its objectives securely, though it had paid a bloody price of 99 killed and 19 missing with a staggering 660 wounded. Even so, the success of the Seventh and Ninety-sixth clearly indicated to General Hodge that Ushijima’s outer line was cracking.

Soldiers of the Twenty-seventh on the twentieth—except for two companies that panicked and fled in disorder when they blundered into an enemy position—were not quite so careful as their comrades in the center and left, probably because they had had a comparatively easy time of it on April 19. Still on the right flank, the New Yorkers moved confidently against a position called Item Pocket, unaware that it was probably Ushijima’s toughest and most cleverly designed fortification. Its name derived from its presence in the I, or “Item,” grid square on the American tactical map. It consisted of coral and limestone ridges running like spokes on a wheel from a swale at its center.

Against it came two battalions of Colonel Gerard Kelly’s 165th Infantry, the first commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James Mahoney on the left and the second under Lieutenant Colonel John McDonough on the right. Resisting them was Lieutenant Colonel Kosuke Nishibayashi’s Twenty-first Independent Infantry Battalion of about six hundred soldiers together with two or three hundred Okinawan conscripts. All had been working for months on Item’s defenses, which they called Gusukuma after a nearby town. There was no safe way to approach the position. Because two bridges on Highway 1 had been knocked out, tanks could not menace it. Every ridge was protected by mortars with machine guns zeroed in from others. Tunnels ran beneath the ridges with openings on either side and on the top. Thus each ridge was a Kakazu in miniature, abundantly stocked with food, ammunition, and water. Until Item fell, there could be no real progress south.

Читать дальше