She was beautiful, but beneath her loveliness, within the necklace of sand and palm, under the coiffure of her sun-kissed treetops with its tiara of jeweled birds, she was a mass of slops and stinks and pestilence; of scum-crested lagoons and vile swamps inhabited by giant crocodiles; a place of spiders as big as your fist and wasps as long as your finger, of lizards the length of your leg or as brief as your thumb; of ants that bite like fire, of tree-leeches that fall, fasten and suck; of scorpions without the guts to kill themselves, of centipedes whose foul scurrying across human skin leaves a track of inflamed flesh, of snakes that slither and land crabs that scuttle—and of rats and bats and carrion birds and of a myriad of stinging insects. By day, black swarms of flies feed on open cuts and make them ulcerous. By night, mosquitoes come in clouds—bringing malaria, dengue or any one of a dozen filthy exotic fevers. Night or day, the rains come; and when it is the monsoon it comes in torrents, conferring a moist mushrooming life on all that tangled green of vine, fern, creeper and bush, dripping on eternally in the rain forest, nourishing kingly hardwoods so abundantly that they soar more than a hundred feet into the air, rotting them so thoroughly at their base that a rare wind—or perhaps only a man leaning against them—will bring them crashing down.

And Guadalcanal stank. She was sour with the odor of her own decay, her breath so hot and humid, so sullen and so still, that all those hundreds of thousands of Americans who came to her during the ensuing three years of war cursed and swore to feel the vitality oozing from them in a steady stream of enervating heat.

The same reaction was felt by Buckner’s troops at the same island—then a huge staging area—and from the same division. Staff Sergeant George McMillan wrote of the Marine replacement on Guadalcanal who ran from his tent at dusk and began to pound his fists against a coconut tree. “I hate you, goddamit, I hate you,” the man cried, sobbing, and from another tent came the cry: “Hit it once for me!”

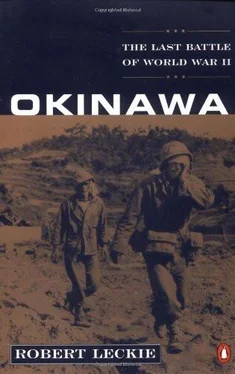

Almost all the troops of Buckner’s Tenth Army shared this loathing, for they had not enjoyed malaria or monsoons or playing hide-and-seek with crocodiles or scorpions, snakes or poisonous centipedes. Indeed, as late as February 1945, General Hodge’s infantry divisions were still mopping up on Leyte in weather and terrain exactly duplicating Guadalcanal’s. Hodge was dismayed. A veteran and respected infantry commander who had served during the mop-up at Guadalcanal under the famous “Lightning Joe” Collins—a future Army chief of staff—and had again defeated the Japanese on New Georgia and Bougainville in the Solomons, as well as Leyte, Hodge knew that his troops were dearly in need of what is today called “Rest and Rehabilitation”: i.e., a rousing beer-and-girls furlough in Melbourne or Sydney, Australia; Wellington, New Zealand; or even Manila. But he was not able to withdraw them from combat until March 1, with D day at the Great Loo Choo scheduled for April 1—exactly a month away. Yet, like the Marines training on Guadalcanal, when the GIs heard that their next campaign was to be on Okinawa, they were inexplicably reassured—perhaps because that island’s highest temperature of 85 degrees in no way approached the “paradise” reading of 120.

Before landing day, meanwhile, the Seventy-seventh Division would be in action on the Kerama Islands. GIs of the Seventy-seventh—known as “the Statue of Liberty Division” because of its shoulder patch—had fought at Guam alongside those fuzzy-cheeked Marine youngsters who pinned on them the nickname of “the old Bastards.” Their commander was Major General Andrew Bruce, who had also led them on Leyte. They were the first in action because Admiral Turner, having already felt the shudder of a “kamikazed” ship beneath his feet, wanted a safe group of islands with deep anchorages to be used as a “ships’ hospital” to which the victims of Japanese suiciders could be towed and repaired. General Hodge also wanted a base for long-range artillery to support his corps’s landing.

On the night of March 25, the Marines of Major Jim Jones’s veteran Reconnaissance Battalion paddled their rubber boats to Kerama to scout the enemy. Reassured by their reports of little opposition, the Seventy-seventh landed there the next day, destroying the lairs of Ushijima’s suicide boats as they took the reef islets one after another.

On the morning of March 29, soldiers of the 306th Infantry [4] This means “regiment,” not division. In American military parlance a regiment formed by three battalions is known by its “arm.” Thus the First Regiment of the First Marine Division is called “First Marines,” or the Seventh Regiment of the First Cavalry Division “Seventh Cavalry.” Too often historians with no military experience mistake these designations to mean division, a much larger formation that—whether infantry, cavalry, or Marine—is usually formed by three “line” regiments and an artillery regiment with other special troops.

realized how cruel their enemy could be. In a valley below their position they found about 150 dead and wounded Okinawan civilians, many women and children among them. They had disemboweled themselves with grenades the Japanese had given them, after telling them the Americans would torture and murder the men and rape the women. In another three days Hodge’s two other divisions would be storming those Hagushi Beaches that Ushijima had chosen not to defend.

Major General James Bradley’s Ninety-sixth Division would be on the right flank of the Twenty-fourth Corps assault. Fresh from Leyte’s jungle and depleted by losses suffered during the fierce battle for Catmon Hill (and like Hodge’s other divisions denied replacements meant for them but sent to Europe to help crush Hitler’s last gasp in the Battle of the Bulge), the Ninety-sixth would face a far more punishing ordeal of blood and mud while attacking Ushijima’s monster Swiss cheese of steel and rock. The soldiers of the Ninety-sixth called themselves “the Dead-eyes” because Brigadier General Claudius Easley, the division’s assistant commander, was a crack shot, a somewhat illogical extension of the part for the whole; especially in a formation so recently formed and new to combat. [5] This comment in no way is intended to demean these gallant GIs—or anyone who has looked upon the horrid Medusa face of battle—but appears only because it might be asked why other nicknames are mentioned but not the Ninety-sixth’s.

In the division’s spearheads would be the 381st Regiment, under Colonel Michael “Screamin’ Mike” Halloran, and Colonel Edwin May’s 383rd. Eddy May was a fine commander whose iron discipline was softened by his compassion for his troops. General Hodge considered him the finest soldier in the entire Twenty-fourth Corps.

On the left flank of Hodge’s zone would be his most experienced division: the Seventh, called “the Hour-Glass Division” because of its shoulder patch and commanded by Major General Archibald Arnold. Its GIs had seen action at Attu in the Aleutians with their subzero cold, then Kwajalein in the Marshalls with its decidedly yet infinitely more amenable heat, and finally those dripping, enervating, malarial jungles of Leyte. In corps reserve would be the 382nd Regiment of the Ninety-sixth Division, while the Seventy-seventh Division still engaged in mopping up the Keramas would be committed to the down-island attack once the landings at Hagushi had been completed, Yontan and Kadena Airfields had been seized, and the Twenty-fourth Corps wheeled right (or south) to attack Ushijima’s Swiss cheese.

Probably the most experienced and famous formation in the American armed forces was the First Marine Division of Major General Geiger’s Third Amphibious Corps. On Guadalcanal alone—where on August 7, 1942, its Leathernecks landed to launch the long, three-year American counter-offensive—they had been in combat a total of 142 days (from the landing date until December 26), probably a record for sustained combat without relief, if such statistics are kept anywhere. During this five-month campaign, which turned the tide of the Pacific War against Japan, these men of “the Old Breed” were responsible for destroying most of the fifty thousand Japanese who fell on “Death Island.” In this dreadful carnage they were assisted by General Collins’s infantry after command passed to the Army on December 9, 1942, and especially by General Geiger’s “Cactus” Air Force, the Marine, Navy, and U.S. Army Air Force pilots who literally blasted the once-dreaded Japanese Zero fighter out of the South Pacific skies while littering the bottom of its waters with sunken Nipponese ships. After “the island,” the First fought in the vicinity of Finschhafen, captured Cape Gloucester on New Britain, and seized Peleliu at a cost of 1,749 dead and wounded while exterminating its 4,000 Japanese defenders. Major General Pedro del Valle commanded the First. Born in Puerto Rico, he had been graduated from Annapolis, serving as an observer in Ethiopia with Italy’s Marshal Pietro Badoglio. Becoming an artillery expert, his guns had much to do with the victory at Guadalcanal.

Читать дальше