Simon Dixon - Catherine the Great

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Simon Dixon - Catherine the Great» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: HarperCollins, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Catherine the Great

- Автор:

- Издательство:HarperCollins

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-06-187179-5

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Catherine the Great: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Catherine the Great»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Admired for her achievements and satirized for her personal life, she wrote the most revealing memoirs by any European ruler. She promoted radical political ideas and emphasized moderation in government. Ruthless when necessary, she charmed everyone she met, joking at private dinner parties in the Hermitage, which she had built for her own use. Determined to endear herself to the Russians, she made religious devotions in which she never believed.

Intimate and revealing, Simon Dixon’s new biography examines the lifelong friendships that sustained the empress throughout her personal life, and places her within the context of the royal court: its politics, its flourishing literature, and the very culture that became central to her exercise of absolute power.

Catherine the Great — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Catherine the Great», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The vagaries of life with Potëmkin help to explain why Easter Sunday found Catherine in wistful mood about Grigory Orlov. ‘If ever you catch sight of him,’ she wrote to Frau Bielke, ‘you will see without contradiction the finest man that you have ever encountered in your life.’ 105Paul and his wife were treated less charitably. Now that Natalia’s wilfulness had begun to emerge, the empress’s patience was starting to wear thin. She mocked the girl’s headstrong profligacy in a letter to Grimm in December: ‘we cannot stand this or that; we are indebted beyond twice what we have, and what we have is twice more than anyone else in Europe.’ 106Now that her son had requested a further 20,000 roubles, she grumbled to Potëmkin that there would be ‘no end to it’: ‘If you count everything, including what I have given to them, then more than five hundred thousand has been spent on them this year, and still they want more. But neither thanks nor a penny-worth of gratitude!’ 107On the whole, however, Catherine’s mood was positive. Even the obligatory summer pilgrimage to the Trinity monastery, with the Chernyshëvs and Kirill Razumovsky in tow, turned out to be ‘very agreeable and a real promenade: we had fine weather and good company and weren’t bored for a moment; I returned in perfect health’. 108

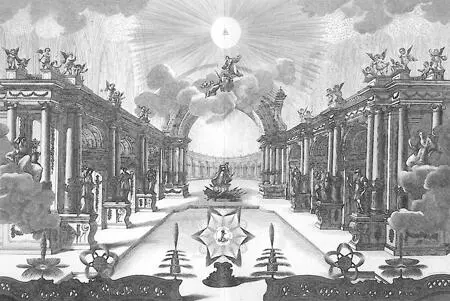

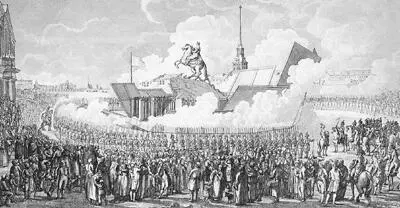

Unfortunately, it was not to last. The peace celebrations had to be postponed when a surfeit of peaches gave her chronic diarrhoea. Onlookers remembered her looking old when she was finally fit to attend having been bled by the medics. On the southern perimeter of the city, fourteen obelisks, each decorated with battle scenes, had been erected to commemorate the greatest victories of the war. From there, the troops marched through the two similarly adorned triumphal arches toward the Kremlin, where Catherine processed down the Red Staircase just as she had at her coronation, only this time in full military uniform. The sound of Slizov’s bell ‘was so tremendous that it seemed that the Ivan Tower itself trembled’, recalled Andrey Bolotov at the beginning of the nineteenth century. ‘Many of us feared it would collapse.’ Bazhenov had initially proposed temples to Janus, Bacchus and Minerva, but Catherine was having none of it. Classical imagery was deliberately excluded as the empress insisted on a range of neo-Gothic structures, erected on Khodynka field at the north-western edge of the city. All of them found their place on an imaginary map of the Black Sea, where Kerch and Yenikale were made to serve as ballrooms, Kinburn as a theatre, and Azov a huge banqueting hall. 109Not since the carousel of 1766 had the Court been treated to such a riot of medievalism. The Black Sea transported to a field near Moscow? It was too much even for Voltaire: ‘I knew very well that the very great Catherine II was the leading person in the whole world; but I hadn’t realised that she was a magician.’ 110

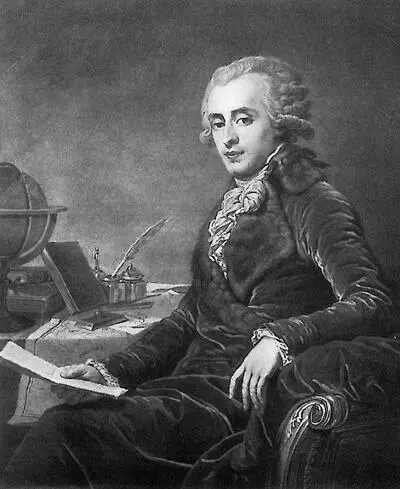

In the midst of this glorious fantasy, the empress had turned her very practical mind to one of the most significant statutes of her reign, the Provincial Reform of November 1775, designed to bring her government closer to the people through a rationalisation of local administration in the wake of the Pugachëv rebellion. Though six surviving drafts in her own hand testify to the depth of Catherine’s commitment to the legislation, the ideas in it came from her advisers. The most influential was Yakov Sievers, who had been brought to Moscow to help her with the reform. ‘Work this out with Sievers,’ ran a typical note on one of her drafts. ‘This is the most stupid article of all,’ she confessed at a moment of particular frustration. ‘My head hurts from it. This endless rumination is very dry and boring. To tell the truth, I am already at the end of my Latin, and I do not know what to do about the Lower Court, the Board of Public Welfare, and the Conscience Court. One word from your excellency on these subjects would be a ray of light, bringing order out of chaos, as when the world was created.’ 111In November, Sievers was appointed Governor General of Tver, Novgorod, Olonets and Pskov, an area larger than many European states in which he was given the honour of being the first to put the new reform into practice. As a sign that they had been appointed as the empress’s personal viceroys, he and Zakhar Chernyshëv in Belorussia were each rewarded with an English silver service weighing over 45 poods. Catherine eventually paid a total of 125,000 roubles for the two services, setting aside a further 42 roubles and 35 kopecks to provide fur coats for officers in the troop which accompanied the final consignment. 112‘I think these regulations are better than my Instruction for the code,’ she told Grimm in January 1776. ‘They are being introduced at this moment in the provinces of Tver and Smolensk where they have been received with open arms.’ 113

The Court had returned to St Petersburg in December. It would be another ten years before Catherine saw Moscow again. By then, the city and the surrounding provinces had been transformed almost beyond recognition, at least in part by her own reforming zeal. Yet even that transformation paled by comparison with the turbulence in the empress’s personal life.

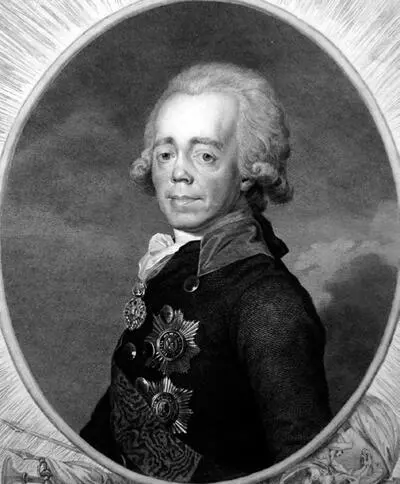

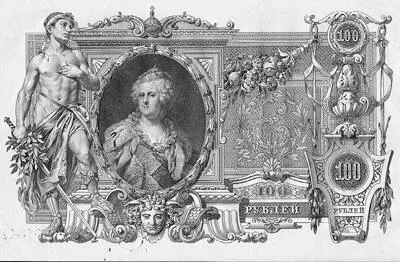

Photographic Insert

CHAPTER TEN

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Catherine the Great»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Catherine the Great» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Catherine the Great» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.