Simon Dixon

CATHERINE THE GREAT

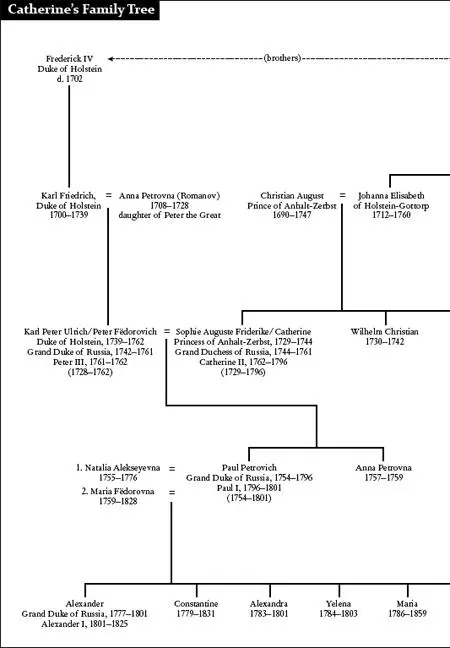

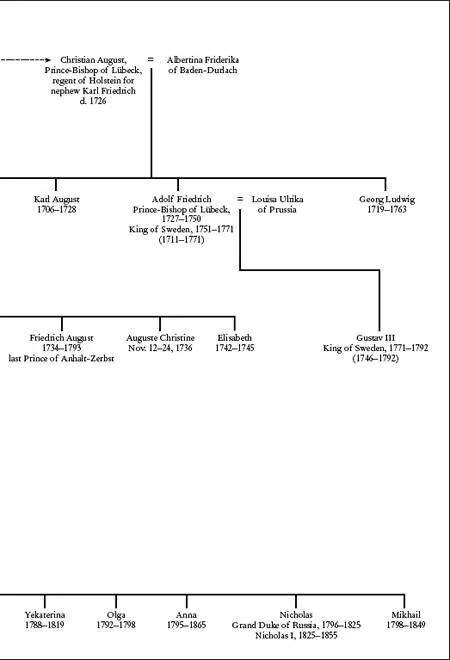

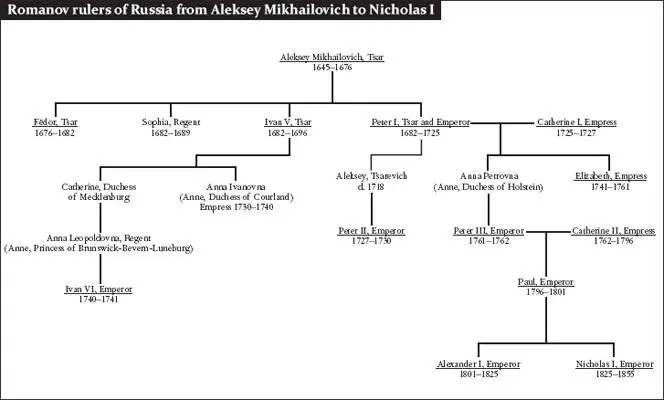

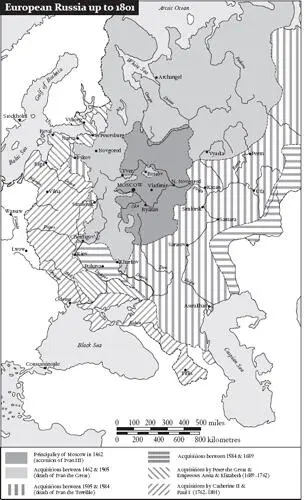

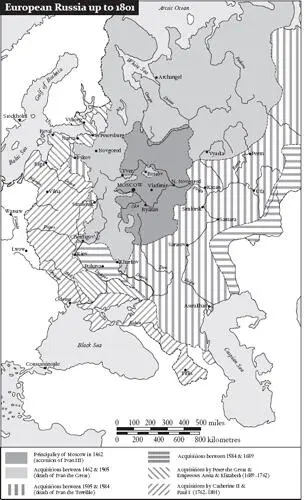

European Russia up to 1801, adapted from Hugh Seton Watson, The Russian Empire 1801–1917 (Oxford, 1967)

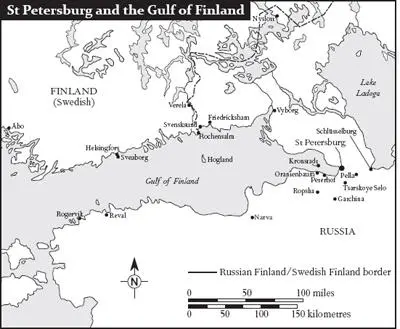

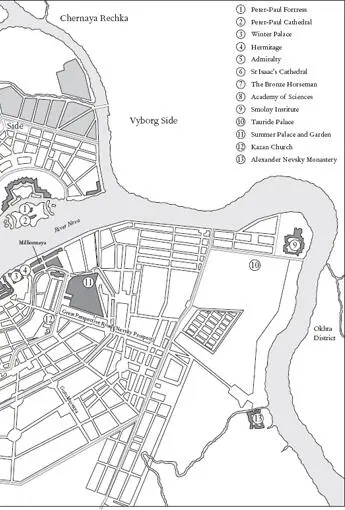

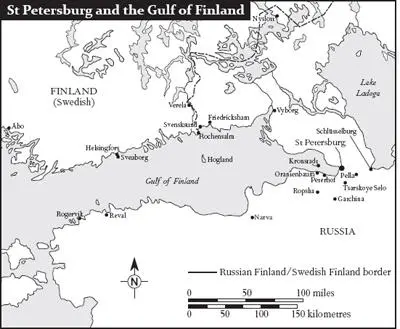

St Petersburg and the Gulf of Finland, adapted from Isabel de Madariaga, Russia in the Age of Catherine the Great (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1981)

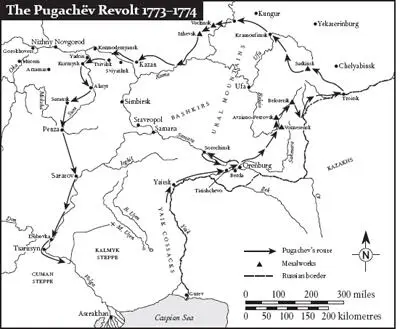

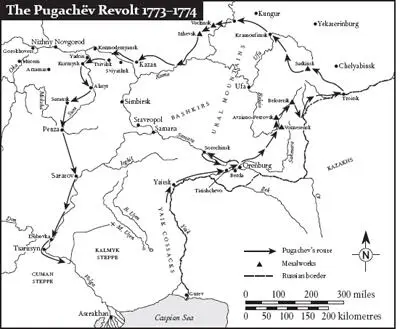

The Pugachëv revolt 1773–4, adapted from John T. Alexander, Autocratic Politics in a National Crisis (Indiana University Press, 1970)

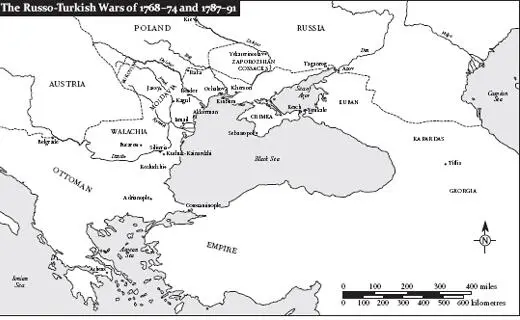

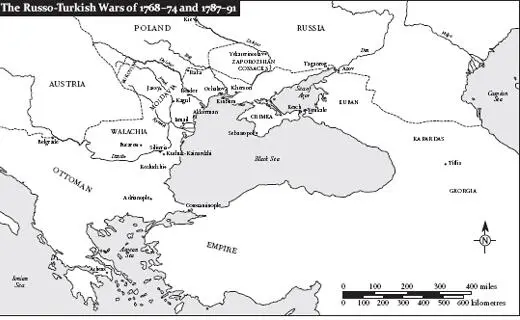

The Russo-Turkish Wars of 1768–74 and 1787–91, adapted from Isabel de Madariaga, Russia in the Age of Catherine the Great (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1981)

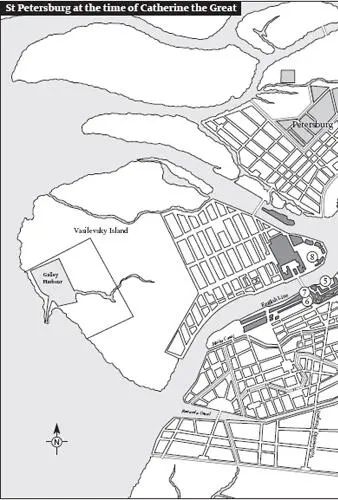

St Petersburg in 1776

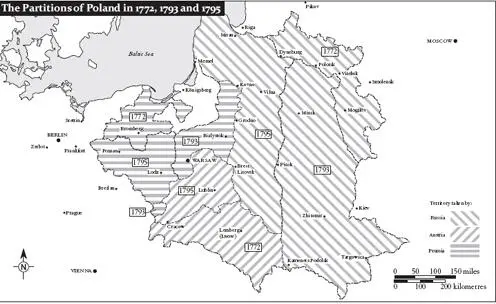

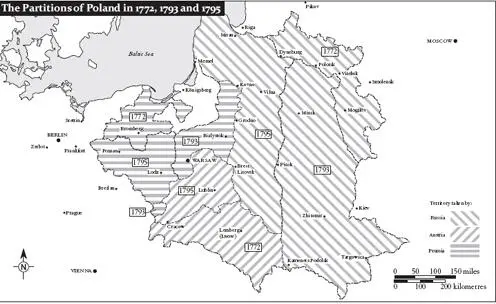

The Partitions of Poland, 1772, 1793 and 1795, adapted from John Doyle Klier, Russia Gathers her Jews: The origins of the ‘Jewish question’ in Russia 1772—1825 (Northern Illinois University Press, 1986)

A NOTE ON DATES, SPELLING, TRANSLITERATION AND NAMES

Dates : All Russian domestic dates are given according to the Old Style (Julian) calendar, which in the eighteenth century was eleven days behind the New Style (Gregorian) calendar in use in most European states by 1800. New Style dates, when given for events outside Russia, are marked NS.

Spelling and punctuation : English spelling and punctuation have generally been modernised, as has the use of capital letters, even in quotations from eighteenth-century sources.

Transliteration : There is no universally satisfactory system of transliteration for the Cyrillic alphabet. While the endnotes and the Further reading section adopt the Library of Congress system now in widespread scholarly use, a modified version is used in the text. Diacritical marks are omitted. The soft vowel ‘ia’ becomes ‘ya’: so, Yaroslavl rather than Iaroslavl; Trubetskaya rather than Trubetskaia. The soft vowel ‘e’ sometimes becomes ‘ye’: so, Tsarskoye Selo rather than Tsarskoe Selo. ‘ii’ and ‘iy’ endings on masculine proper names become ‘y’: so, Vyazemsky not Viazemskii. The soft vowel ‘e’, pronounced ‘yo’, is given as ‘ë’: so, Potëmkin rather than Potemkin or Potyomkin.

Names : Catherine’s name, along with those of other ruling monarchs, is anglicised according to convention; otherwise the Russian is normally retained, e.g. Nicholas I but Nikolay Novikov. In some cases, e.g. Peter and Alexander, the anglicised version is always used. Although Russian makes extensive use of the patronymic in forms of address, most Russian names are given with Christian name and surname only: so Nikolay Novikov, rather than Nikolay Ivanovich Novikov or N. I. Novikov.

Jesus Christ, Napoleon and Richard Wagner are said to have inspired more biographies than any other figures in history. Catherine the Great cannot be far behind. Fascinated by a German princess who captured the Russian throne and corresponded with the leading minds of her age, her contemporaries started to tell her story from the moment she died on 6 November 1796. Ever since, her political achievements as ruler of the most powerful emergent empire in Europe have been set against rumours about the amorous liaisons on which she embarked in search of elusive personal fulfilment.

Over 200 years after the empress’s death, when both aspects of her life still make headlines in Russia and the West, my aim has been to bridge the gap between formidable historical scholarship and the popular accounts that risk trivialising a woman whose life requires no embellishment to reveal its interest and importance. There is no need to invent her conversations: though her writings can rarely be taken at face value, they tell us much about her active mind. And there is no shortage of acute contemporary comment on her personality and reign (what posterity made of it is the subject of my final chapter). Unless otherwise acknowledged, translations from these sources are my own, though readers who want to explore for themselves now have access to a growing range of excellent English versions, listed in the Further reading section. In addition to identifying the sources of my quotations, the endnotes offer a further (if necessarily inadequate) guide to the scholarship on which I have drawn. A comprehensive list would fill a book far larger than this one.

The Russian historian and journalist Vasily Bilbasov made the same discovery at the end of the 1880s. In addition to filling a fat bibliographical volume, he took more than a thousand lively pages to cover only half of Catherine’s life before the reigning tsar, Alexander III, intervened to prevent further revelations about his controversial predecessor. Since comprehensiveness is clearly an impossible goal, it is important to have a guiding purpose in choosing what to discuss and what to omit. In attempting to give a fully rounded portrait of the empress, I have taken a broadly chronological approach that helps to emphasise the very wide variety of problems with which an absolute monarch was confronted at any one time. (Corrections to generally accepted dates are largely silent, except where they significantly revise our understanding of the course of events, as, for example, in the case of the funerals of Empress Elizabeth and Alexander Lanskoy.) Above all, however, I have sought to recover a sense of place, situating Catherine in the context of the Court society in which she grew up in Germany and lived most of her long life in Russia. For all that she did to reshape the values of the Court of St Petersburg, it still preserved in the 1790s many of the features of the Baroque Courts which she had first experienced, at Stettin, Zerbst and Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. Here the Court is understood in the multiplicity of senses familiar to her and her contemporaries: an institution alive with intrigue extending from the monarch at its heart to the servants at its outer penumbra; a network of rival aristocratic clienteles at the centre of politics in much of Europe before the French Revolution; the symbolic authority to which foreign ambassadors were accredited; an extraordinary range of palaces, both urban and surburban; and a glittering cultural icon representing the power and majesty of the ruler to her subjects, great and small. That was how Catherine experienced the Court. And no single event did more to reveal its kaleidoscopic significance than her coronation, with which my version of her story begins.

Читать дальше