The Life of the Great Explorer

HARPER PERENNIAL London, New York, Toronto and Sydney

HARPER PERENNIAL London, New York, Toronto and Sydney

For Margaret

Cover Page

Title Page Wilfred Thesiger The Life of the Great Explorer

Dedication For Margaret

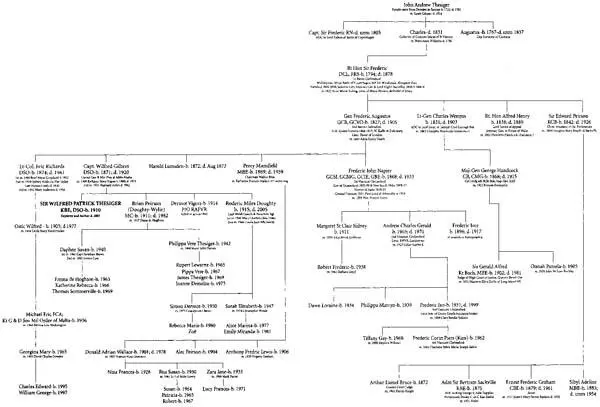

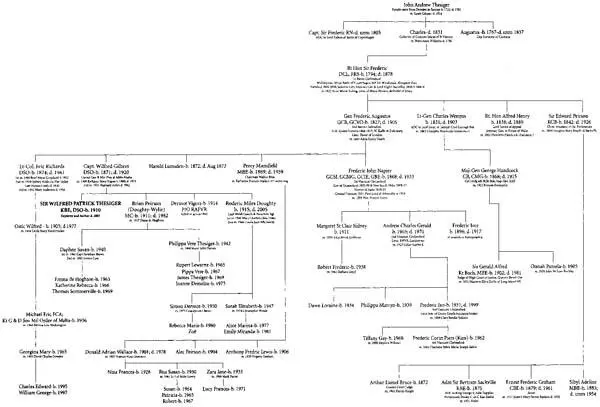

THESIGER FAMILY (1722-2005) THESIGER FAMILY (1722-2005)

INTRODUCTION

ONE The Emperor Menelik’s ‘New Flower’

TWO Hope and Fortune

THREE Gorgeous Barbarity

FOUR ‘One Handsome Rajah’

FIVE Passages to India and England

SIX The Cold, Bleak English Downs

SEVEN Eton: Lasting Respect and Veneration

EIGHT Shrine of my Youth

NINE The Mountains of Arussi

TEN Across the Sultanate ofAussa

ELEVEN Savage Sudan

TWELVE The Nuer

THIRTEEN Rape of my Homeland

FOURTEEN Among the Druze

FIFTEEN The Flowering Desert

SIXTEEN Palestine: Shifting Lights and Shades

SEVENTEEN Prelude to Arabia

EIGHTEEN Arabian Sands

NINETEEN Marsh and Mountain

TWENTY Among the Mountains

TWENTY-ONE A Winter in Copenhagen

TWENTY-TWO Camel Journeys to the Jade Sea

TWENTY-THREE With Nomadic Tribes in Other Lands

TWENTY-FOUR Kenya Days

EPILOGUE

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Praise

By the same author

Copyright

About the Publisher

THESIGER FAMILY (1722-2005)

‘Even now, after so many years, I can still remember Wilfred Thesiger as he was when I first saw him,’ was how Thesiger suggested I might begin his biography. To this he had added: ‘The rest is up to you.’ 1

I met Thesiger for the first time in June 1964 at his mother’s top-storey flat in Chelsea. He was then aged fifty-four. He was sunburnt, tall, with broad shoulders and deep-set grey eyes. As we shook hands I noticed the exceptional length of his fingers. He wore an obviously well-cut, rather loose-fitting dark suit. I remember clearly that he smelt of brilliantine and mothballs. He spoke quietly, with an air of understated authority. His voice was high-pitched and nasal; even by the standards of that time, his rarefied pronunciation seemed oddly affected. He had a distinctive habit of emphasising prepositions in phrases such as ‘All this was utterly meaningless to me’. He moved slowly and deliberately, with long, ponderous strides; yet he gave somehow the impression that he was also capable of lightning-fast reactions. Later, I heard that he had been a source of inspiration for Ian Fleming’s fictional hero James Bond. Whether or not this was true, Thesiger, like Bond, was larger than life; and like Bond, he appeared to have led a charmed existence.

He introduced me to his mother, Kathleen, who had retired early to bed. Cocooned in a woollen shawl and an old-fashioned lace-trimmed mobcap, she lay propped up on pillows, with writing paper and books spread out on the bedcover within easy reach. Thesiger left us alone for a few minutes while he carried a tray with a decanter of sherry and glasses to the sitting room. It was then that his mother offered me the unforgettable advice: ‘You must stand up to Wilfred.’ 2

Thesiger preferred to sit with his back to the window, in the dark shadow of a high-backed chair. At intervals he fingered a string of purple glass ‘worry beads’ that lay on the small table at his elbow. He talked energetically and fluently in reply to enquiries, but he himself asked few questions, and instead of taking up a fresh theme he sat quietly, staring at me, until I questioned him again. When I could think of nothing to say, or to ask, he reached again for the purple beads. Meanwhile he scarcely had touched his thimbleful of sherry.

His mother’s flat, to which Thesiger returned for two or three months every year, was like a catalogue raisonnee of his life and travels. Danakil jilis in tasselled sheaths hung beside framed black-and-white Kuba textiles from the Congo. There were silver-hilted Arab daggers and ancient swords in silver-inlaid scabbards. Medals honouring Thesiger’s achievements as an explorer and, in his youth, as a boxer were displayed in velvet-lined cases. A portrait of Thesiger painted in 1945 by Anthony Devas hung on the right of the sitting room fireplace. On the wall opposite, three tall glass-fronted cabinets held part of his collection of rare travel books devoted to Arabia, Africa and the Middle East. His mother had brought the cabinets to London in 1943 from their former home in Radnorshire. Thesiger commented proudly: ‘I can’t begin to imagine how my mother knew they would fit into this room. It was remarkable how she did this. But, there again, my mother is a very remarkable person.’ 3

In a cupboard in Thesiger’s bedroom were stored the sixty or more landscape-format albums of black-and-white photographs which he often described as his ‘most cherished possession’. 4As far as I remember he did not produce these albums during my first visit, but over the years I became very familiar with the wonderful images they contained. Only some time later did he show me his collections of travel diaries, notebooks and annotated maps describing his journeys. Not until some years after she had died did he encourage me to read letters he had written, many from outlying places, to his mother, who to her eternal credit preserved them with care, as she had preserved those Wilfred’s father had written a generation before.

One memory stands out from the vaguer recollections of that first visit. To my surprise, as I was leaving Thesiger took out a pocket diary, consulted it for a moment and said: ‘If you’ve nothing better to do next Sunday, why don’t you come along and we’ll cook ourselves supper. My mother’s housekeeper is away for the night, but we can heat up some soup and scramble an egg or two.’ He grinned and added: ‘That’d be fun.’ 5This unexpected invitation marked the beginning of a friendship that lasted for almost forty years.

I have heard it said that Thesiger was very straightforward, uncomplicated, easy to get to know and to understand. To some people he may have appeared like that; and of course, everyone who met him (whether they knew him intimately or hardly at all) received a slightly different impression. But even his oldest friends, who had known him since his schooldays, could not quite agree about certain seemingly paradoxical aspects of Thesiger’s character and temperament. Most of them, however, accepted that he was a veritable maze of contradictions; and, if the truth be told, in some ways his own worst enemy. Like the Bedu of the Arabian desert, he was a man of extremes. He could be affectionate and loving (for example towards his mother), yet he was capable of spontaneous, bitter hatred; he was either very cautious or wildly generous with his money and possessions; he was normally fussy and meticulous, but he could be astonishingly careless and foolishly improvident; he relished gossip, yet was uncompromisingly discreet; his touching kindnesses contrasted with sometimes appalling cruelty. He denied being possessive and criticised others who were, including his friend the writer T.H. White, and his own mother, who was by nature possessive – as indeed he was himself. Being possessive, and yet desperately needing to be possessed, was part of Thesiger’s chronic sense of insecurity, which resulted from traumas he suffered during his childhood in Abyssinia and England. His vices were fewer, less extreme and yet more conspicuous than his many virtues. The greatest of these – immense and selfless bravery, compassion, determination, integrity and creative energy – enabled him to achieve his outstanding feats of exploration and travel, and to record them with a matchless brilliance in his photography and in his writing.

Читать дальше

HARPER PERENNIAL London, New York, Toronto and Sydney

HARPER PERENNIAL London, New York, Toronto and Sydney