A year after Menelik’s first, paralysing stroke, ‘Conditions in Addis Ababa and in the country as a whole were already chaotic…They were soon to become very much worse. In and around Addis Ababa murder, brigandage and highway robbery increased alarmingly; in restoring order, public hangings, floggings and mutilations had little effect. The town was filled with disbanded soldiery from Menelik’s army, and on the hills outside were camped the armies of the various contenders for power.’ 10

Here, at the heart of Menelik’s remote African empire, threatened by anarchy and bloodshed, Thesiger’s father took up his official duties at the British Legation in December 1909. He and his young bride, who was four months pregnant, adjusted to married life in these primitive surroundings as they waited anxiously and eagerly for the birth of their first child the following year.

In March 1911, nine months after the birth of their eldest son, Wilfred Thesiger’s father wrote in a romantic mood to his wife, who was then in England and pregnant for the second time: ‘What a wonderful thing it is to be married and love like we do, and all has come because you once said “yes” to me in a hansom and gave yourself to me.’ 1

Captain the Honourable Wilfred Gilbert Thesiger was aged thirty-eight and Kathleen Mary Vigors was twenty-nine when they married on 21 August 1909 at St Peter’s church, Eaton Square, in the London borough of Westminster. The ceremony in this fashionable setting was conducted by the Reverend William Gascoigne Cecil, assisted by the Reverend Arthur Evelyn Ward, whose marriage to Kathleen’s younger sister Eileen Edmee took place in November that same year. The Thesigers made a handsome couple on their wedding day. Kathleen’s slender build and radiantly healthy complexion, set off by luxuriant waves of auburn hair, perfectly complemented Wilfred Gilbert, who stood over six feet, and was lean and muscular, with broad, sloping shoulders. His gaunt, rather delicate features, still sallow after two years’ exposure to the African sun, were clean-shaven except for a heavy moustache, and his dark-brown hair was brushed from a centre parting. Like his late father, General Lord Chelmsford, Wilfred Gilbert Thesiger was reliably discreet, formal and pleasantly reserved.

Wilfred Gilbert and Kathleen’s was the third wedding uniting two generations of their families. Handcock sisters, who were first cousins of Kathleen’s mother, had married distinguished younger sons of the first Lord Chelmsford. In 1862 Henrietta Handcock married the Honourable Alfred Henry Thesiger, a Lord of Appeal and Attorney-General to the Prince of Wales. The following year, Henrietta’s elder sister Charlotte Elizabeth married Alfred Henry’s elder brother, the Honourable Charles Wemyss Thesiger, a Lieutenant-General in the Hussars. In August 1909, witnesses to the Thesigers’ marriage included Kathleen’s widowed mother Mary Louisa Helen Vigors, Wilfred Gilbert’s elder brother Percy Mansfield Thesiger, and Count Alexander Hoyos, a Secretary at the Austrian Embassy and a friend of the bridegroom. In his autobiography, Wilfred Thesiger portrayed his father as ‘intensely and justifiably proud of his family, which in his own generation had produced a viceroy, a general, an admiral, a Lord of Appeal, a High Court judge and a famous actor. Intelligent, sensitive and artistic, with a certain diffidence which added to his charm, he was above all a man of absolute integrity.’ 2

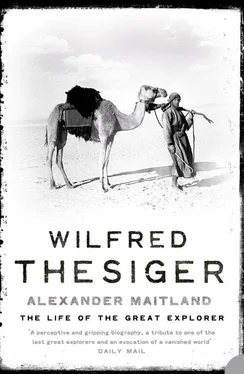

Wilfred Gilbert painted in watercolours, wrote verse and also played the cello. 3By his early thirties he had already had a distinguished career in the Consular Service, and had been awarded a DSO in the Boer War. Perceptive studio portraits by Bertram Park, a society photographer in Dover Street, London, highlighted these compatible yet contrasting facets of his life and character. On the one hand, Park captured the thoughtful, determined expression of a soldier and administrator accustomed to authority; on the other, he evoked the introspective, wistful gaze of an artist and a poet.

Thesiger described his mother Kathleen as attractive, brave and determined, a woman who had dedicated herself to her husband ‘in the same spirit shown by those great nineteenth-century lady travellers Isobel Burton and Florence Baker…ready to follow [him] without question on any odyssey on which he might embark’. 4‘A photograph of my mother at that time [also taken by Bertram Park] shows a beautiful, resolute face under waves of soft brown hair…Naturally adventurous, she loved the life in Abyssinia, where nothing daunted her. She shared my father’s love of horses and enjoyed to the full the constant riding. Like him, she was an enthusiastic and skilful gardener…Since she was utterly devoted to my father, her children inevitably took second place. In consequence in my childhood memories she does not feature as much as my father; only later did I fully appreciate her forceful yet lovable character.’ 5

When he wrote about his father’s family, Thesiger saw no reason to include the generations of ancestors before his grandfather, the famous general and second Lord Chelmsford. He defended this, saying: ‘ The Life of My Choice was about me and the life I had led. My father and, later on, my mother were tremendously influential and I was fascinated by what my grandfather had done. These things affected me, but I can’t have been affected by relatives living at the time of Waterloo. To suggest that I might have seems, to me, utter nonsense. It would never have occurred to me to spend months studying my ancestors, to see whether or not there might be any resemblance between some of them and myself.’ 6

Whereas later generations of Thesigers have been well-documented, little is known about Johann Andreas Thesiger who emigrated from Saxony to England in the middle of the eighteenth century and in due course established the Thesigers’ English line. According to family records, Johann Andreas, now usually known as John Andrew, was born in Dresden in 1722. He married Sarah Gibson from Chester, and fathered four sons and four daughters. John Andrew died in May 1783, 7and was survived by his wife, who died almost thirty-one years later, in March 1814. John Andrew was evidently intelligent, amenable and hardworking. Although the young Wilfred Thesiger scoffed at efforts to prove similarities between his remote ancestors and later generations of his family, John Andrew’s sons, like their father, had been clever and diligent. His great-grandson Alfred Henry, who became a Lord of Appeal and Attorney-General, was described as ‘extremely industrious’, while Alfred Henry’s nephew Frederic, the first Viscount Chelmsford, was known to work ‘very hard’, as was Frederic’s younger brother, Wilfred Gilbert Thesiger.

In The Life of My Choice , Wilfred Thesiger underlined his father’s tireless capacity for hard work: ‘By December 1917 my father badly needed leave. The altitude of Addis Ababa, at eight thousand feet, was affecting his heart. He had been short-handed, overworked and under considerable strain.’ 8As for Thesiger himself. He was once described by his lifelong friend John Verney as ‘the world’s greatest spiv’. 9Yet when writing a book he often worked for as many as fourteen hours a day, and even in his eighties his powers of concentration and his ability to work long hours for weeks at a time appeared to be undiminished.

From the time he arrived in England, John Andrew Thesiger earned his living as an amanuensis or private secretary to Lord Charles Watson-Wentworth, the second Marquess of Rockingham, who led the Whig opposition and twice served as Prime Minister, in 1765-66 and again in 1782, the year he died. As well as his native German, John Andrew evidently spoke and wrote fluently in English, and possibly several other languages besides. His eldest son Frederic, we know, understood Danish and Russian.

Читать дальше