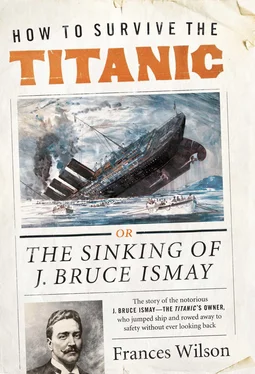

Meanwhile, compensation claims were being presented. In October 1913, when an Irish farmer sued for the loss of his son he was represented by Ismay’s adversary, Thomas Scanlan, who interrogated Lightoller for a second time, on this occasion before a jury. The White Star Line was now found guilty of negligence, the jury concluding that the danger to the ship was foreseen and the speed reckless. White Star appealed but the verdict was upheld; the conclusions drawn by the British Board of Trade inquiry had been made to look ridiculous. In America, at the instigation of the Titanic Survivors’ Committee, suit was commenced against White Star on behalf of the steerage passengers. Those survivors who had not been called as witnesses at the Senate inquiry now provided depositions to show that Ismay had been running the ship. Elizabeth Lines, a first-class passenger returning from Paris for her son’s graduation ceremony, testified that after lunch on the day before the collision she had overheard a two-hour conversation between Ismay and Captain Smith. The two men were taking coffee in the lounge, a few tables away from her own, and Mrs Lines had her back to where they were sitting. ‘At first I did not pay any attention to what they were saying, they were simply talking and I was occupied, and then my attention was arrested by hearing the day’s run discussed, which I already knew had been a very good one in the preceding twenty-four hours, and I heard Mr Ismay — it was Mr Ismay who did all the talking — I heard him give the length of the run and I heard him say “Well, we did better today than we did yesterday, we made a better run today than we did yesterday, we will make a better run tomorrow. Things are working smoothly, the machinery is bearing the test, the boilers are working well.” They went on discussing it, and then I heard him make the statement, “We will beat the Olympic and get in to New York on Tuesday.”’ Those exact words, Mrs Lines said, ‘fixed themselves’ on her mind. Captain Smith had said nothing throughout and Ismay’s tone had been ‘dictatorial’. The owner ‘asked no questions, he made assertions, he made statements. I did not hear him defer to Captain Smith at all.’ Elizabeth Lines admitted that she had only seen Ismay once in her life, twenty years before when he lived in New York, but insisted that she knew ‘for certain’ the voice belonged to him. He was the same man who ate his meals ‘at the Captain’s table on the Captain’s right’. 3

Emily Ryerson now provided the testimony she had withheld from Senator Smith during the US inquiry. She had been walking on the deck with Marian Thayer when Ismay appeared and ‘produced from his pocket a telegram’. ‘We are in amongst the icebergs,’ he said, and will ‘start some extra boilers tonight’. Being in a state of ‘mental distress’ at the time and finding his company boring, she had barely listened. Her statement was less a memory than ‘the record of an impression left on my mind’, but Ismay’s manner was ‘that of one in authority and the owner of the ship and that what he said was law. If this can be of service to anyone I do not wish to be silent or seem to be protecting him.’ 4Soon after Mrs Ryerson made this statement, Marian Thayer stopped replying to Ismay’s letters.

On 24 March 1914, before the King’s Bench Division of His Majesty’s High Court of Justice, Ismay once again told his story, this time to George Betts, the New York attorney for the American claimants. As Ismay would not return to America, Betts had come to him. He was questioned about his position as a ‘conspicuous passenger’, about his understanding of the Marconigram from the Baltic, his discussion with Joseph Bell at Queenstown concerning the ship’s speed trials, and his communication with Captain Smith following the collision. Ismay’s rhetorical device was now vagueness, his manner that of someone grown tired of the facts. He casually contradicted himself, and to ensure that what he said today bore some relation to what he had said at the inquiries two years before, he requested reminders of his previous replies to the same questions.

When asked with whom he dined on the night of the accident, he said ‘Dr O’Loughlin, I think it was.’ Of the time at which the two men ate, he replied ‘somewhere about half past 7… I think it was’. The captain was dining ‘with some ladies, I think Mrs Widener’; as to the presence at the Wideners’ dinner party of Mrs Thayer, ‘I do not know whether she was there or not’. Asked to confirm whether the day on which he was handed the Marconigram from the Baltic was Sunday 14 April, Ismay said that it was a Sunday but that he ‘did not know the date’; asked whether he had shown the Marconigram to anybody else on the ship, he said that he ‘did not remember’. About whether he remembered ‘speaking on the afternoon of Sunday on deck to Mrs Ryerson and showing her the message’, he remembered speaking only ‘to Mrs Thayer’. The Marconigram, Ismay said, did not make ‘very much impression on me with regard to the ice’, and as for the question of speed, he had ‘never really considered the matter’. He described going onto the bridge in his pyjamas and talking to the Captain, and said that it was a ‘long time’ after this that he realised the ship would sink. Questioned as to whether he was familiar with the practice of putting ice warnings on the board of the chart room, Ismay said that ‘it would be a natural thing to do’. He swore that he had never dined at the Captain’s table — this had been the privilege of the Thayer family — but on one occasion, he now ‘believed’, the Captain may have dined with him. He had ‘never’, Ismay said, sat ‘in the ship’s lounge discussing the passage with Captain Smith’, and he had ‘never’ told the Captain that ‘we will beat the Olympic and get into New York on Tuesday’.

The claimants’ case against the White Star Line finally commenced in the United States Court in New York on 22 June 1915. Claims ranged from $50, by Eugene Daly, for a set of bagpipes, to $177,352.75 by Mrs Cardeza — the richest passenger on the ship — for the loss of fourteen trunks, three crates, a jewel box and four suitcases. Among the other items passengers claimed for were a signed photograph of Garibaldi, an Arab costume, a marmalade machine and I0lb of tea. With the help of a host of new witnesses, including Karl Behr and Jack Thayer, George Betts from the law firm of Hunt, Hill and Betts argued that Ismay had behaved on board as though he were a super captain, while the defence contended that he was travelling as an ordinary passenger. On 28 July 1916, the judge signed the decree ending all Titanic suits and White Star settled out of court, paying out $664,000 in compensation for loss of life and luggage, the price of a life being $30,000. It was a tacit admission of guilt.

In 1925, the IMM, which had never been profitable, got rid of its foreign flag holdings; passenger airlines crossing the Atlantic would soon be making steamships a thing of the past. Two years later White Star was bought by Lord Kylsant, chairman of the expanding Royal Mail Steam Packet Company. It was Kylsant, known as Lord of the Seven Seas, who finally sank the White Star Line; in 1931 he was found guilty of filing fraudulent financial reports, stripped of his title and sentenced to twelve months in Wormwood Scrubs. The government stepped in to save the company, forcing them into a merger with their great rival, Cunard. In 1933, Thomas Ismay’s life’s work became known as Cunard White Star Limited, and the Liverpool and London offices closed down.

As someone who feared chaos, Ismay now arranged for himself a life of routine. Easter was spent golfing at the Gleneagles Hotel in Scotland and summers were spent in Ireland. For the rest of the year he would catch the train every Sunday afternoon from Euston to Liverpool Lime Street, draw the blinds of his private compartment and eat the cold supper he had brought with him. He would then stay three nights in the city’s North Western Railway Hotel and attend to his business meetings, returning to London on Wednesday evening. He was still director of the London and North-Western Railway (a forerunner of British Rail), of the London and Globe Insurance Company, the Sea Insurance Company and the Pacific Loan and Investment Company, and he was chairman of the Asiatic Steamship Company and the Liverpool and London Steamship Protection and Indemnity Association, whose minutes show that the Titanic was mentioned on a weekly basis in relation to insurance claims. If Ismay went alone to a concert at St George’s Hall, as he preferred to do, he booked two seats and placed his hat and coat on the second one. Florence arranged her bridge parties for the half of the week that her husband was away, and when the couple hosted the occasional dinner — for never more than eight people — Bruce would always be given his own plate of cold turkey.

Читать дальше