Frances Wilson

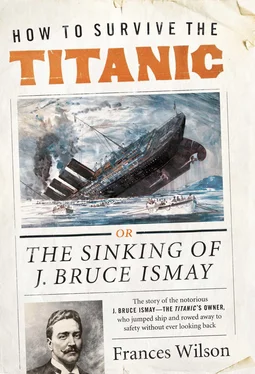

HOW TO SURVIVE THE TITANIC

or

THE SINKING OF J. BRUCE ISMAY

J. Bruce Ismay was managing director and chairman of the White Star Line, the company that built the Titanic . When the ship struck an iceberg on her maiden voyage, Ismay, who was on board, jumped into one of the last lifeboats to leave. He subsequently became, according to a headline, ‘The Most Talked of Man in All the World’. These are some of the things that were said about him:

‘Mr Ismay’s place as a man and as the responsible director of the White Star Line was on the planks of the imperilled ship. He esteemed his life higher than honour and duty, and as long as this life, which he was so anxious to save, lasts he will bear on his forehead the mark of Cain, the mark of the contempt of all men of honour’

–

Frankfurter Zeitung

‘Mr Ismay cares for nobody but himself. He cares only for his own body, for his own stomach, for his own pride and profit’

–

New York American

‘The humblest emigrant in steerage had more moral right to a seat in the lifeboat than you’

– John Bull

‘By the supreme artistry of Chance… it fell to the lot of that tragic and unhappy gentleman, Mr Bruce Ismay, to be aboard and to be caught by the urgent vacancy in the boat and the snare of the moment’

– H. G. Wells,

Daily Mail

‘You will hunt poor Ismay from court to court, as if he were the only man that was saved’

– G. K. Chesterton,

Illustrated London News

‘I have always felt that he was the most misunderstood and misjudged character of the early part of the century’

– Wilton Oldham,

The Ismay Line

‘The parallel with the tale of Conrad’s Lord Jim will occur to most of us’

–

New York Tribune

The cover of a 1906 White Star Line passenger list.

There was a Ship, quoth he

– Samuel Taylor Coleridge,

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

I took the chance when it came to me. I did not seek it.

J. Bruce Ismay,

New York World

Ah! What a chance missed! My God! What a chance missed!

Joseph Conrad,

Lord Jim

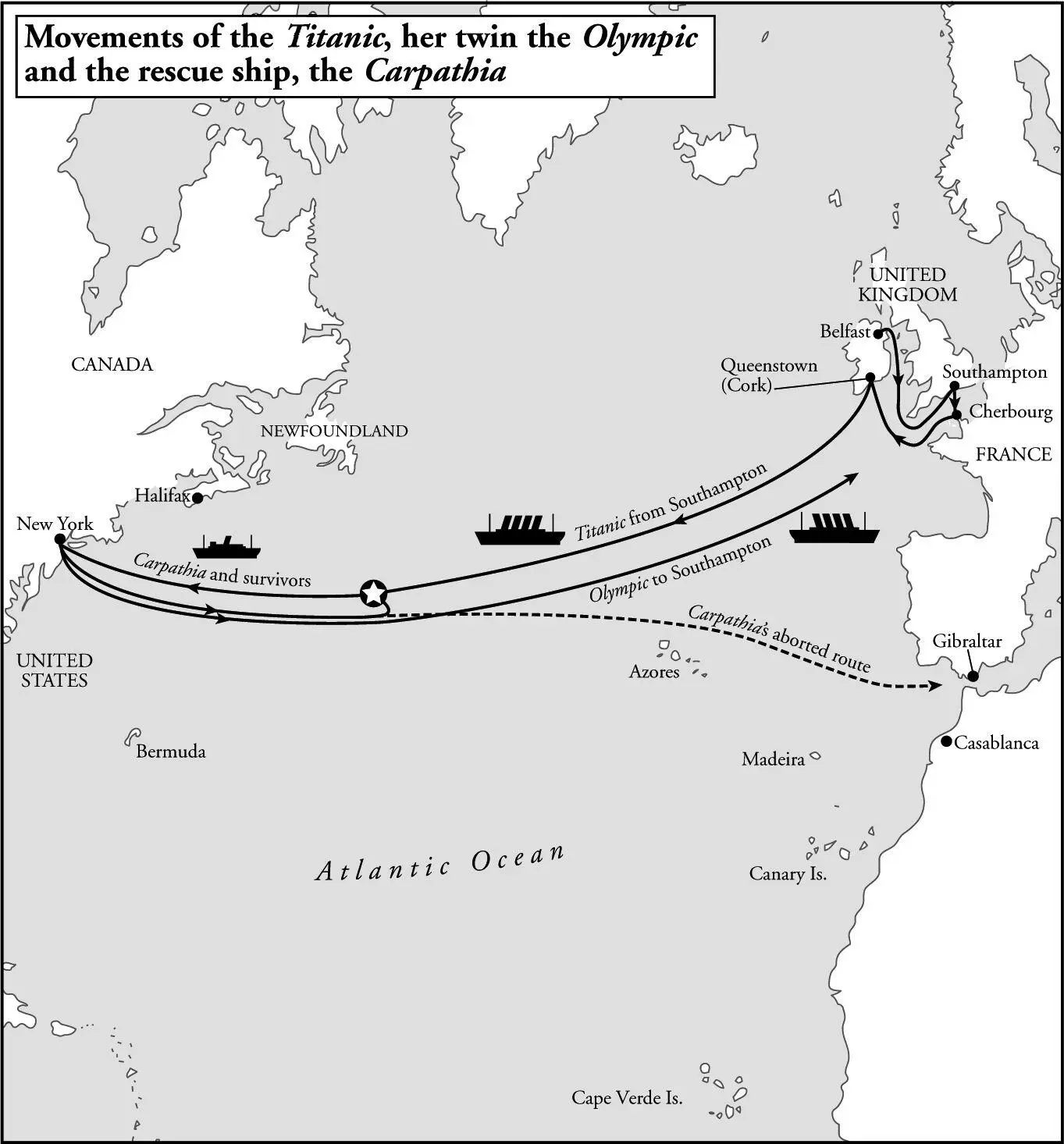

On the night his ship struck the iceberg, J. Bruce Ismay dined in her first-class restaurant with Dr William O’Loughlin, surgeon of the White Star Line for the previous forty years. The two men had shared similar meals on similar crossings, Ismay in his dinner jacket, O’Loughlin in his crisp white uniform. In another part of the dining room a dinner party was taking place in honour of the Captain, E. J. Smith. It was Sunday, 14 April 1912, and the Titanic, four days into her maiden voyage, was heading towards New York where she was due to arrive early on Wednesday morning.

After coffee and cigarettes, Ismay retired to his stateroom and was asleep by 11 p.m. He was aware that they were heading into an ice region because at lunchtime that day Captain Smith had handed him a Marconigram from another White Star liner, the Baltic, warning of ‘icebergs and large quantity of field ice’ about 250 miles ahead on the Titanic ’s course. Ismay had casually slipped the message into his pocket, taking it out later that afternoon to show two passengers, Mrs Marian Thayer and Mrs Emily Ryerson, and handing it back to Captain Smith shortly before supper so that the warning could be displayed in the officers’ chart room. Ismay was not concerned about ice when he turned out his light; it must have been the calmest night ever known on the North Atlantic. The sky was a vault of stars, the sea a sheet of still black, the Titanic — the largest moving object on earth — was 46,000 tons of steel and the height of an eleven-storey building. To stand on the deck that night, a passenger later said, ‘gave one a sense of wonderful security’.

The collision occurred at 11.40 p.m.; the ship’s speed was 22 knots and it took ten seconds for the iceberg to tear a 300-foot gash along her starboard side, slicing open four compartments. The sound, one woman recalled, was like the scraping of a nail along metal; to another it felt as though the ship ‘had been seized by a giant hand and shaken once, twice, then stopped dead in its course’. Ismay awoke, his first thought being that the Titanic had lost a blade from one of her three propellers. He put on his slippers and padded down the passageway to ask a steward what had happened. The steward did not know, so Ismay returned to his room, put an overcoat and a pair of black evening trousers on top of his pyjamas and, still in his slippered feet, went onto the bridge where Captain Smith told him they had struck a berg. Was the ship damaged? Ismay asked. ‘I am afraid she is,’ the Captain replied.

The crew were now stirring and a quiet commotion had begun, with stewards knocking on doors to tell the passengers to collect their lifejackets and come up on deck. When Joseph Bell, the Chief Engineer, appeared on the main staircase Ismay asked for his opinion of the damage. Bell said that he thought, or he hoped, that the pumps would control the water for a while. Ismay briefly returned to his room, but he was soon back on the bridge and heard the Captain give the order for lifeboats to be prepared, and for women and children to go first. He then walked along the starboard side of the ship where he met one of the officers and told him to start getting the boats out. It was now five minutes after midnight. I rendered all the assistance I could, Ismay later said. I helped as far as I could. Staying on the starboard side throughout, he called for women and children to fill Lifeboats 3, 5, 7 and 9 (Lifeboats 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14 and 16 were located on the port side). When thirteen of the standard boats were away (2, 4 and 11 had yet to be launched), Ismay helped to load Collapsible C, which was one of the Titanic ’s four Engelhardt canvas-sided life-rafts. Twenty-one women, two men, fourteen young children and six crew were given seats: forty-three passengers so far in a boat which allowed for a maximum of forty-seven. Chief Officer Wilde ordered Collapsible C to be lowered. The deck was flooding and the ship listing heavily. I was standing by the boat, Ismay said. I helped everybody into the boat that was there, and, as the boat was being lowered away, I got in. He got into the fourteenth boat to be launched and the third-to-last boat to leave the Titanic on the starboard side.

Ismay later claimed that he had left in the last boat on the starboard side. Other versions of his departure from the ship exist, none of which agree. In the US inquiry, which began in New York’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel five days later, and the British Board of Trade inquiry which opened in London the following month, every man called to the stand had to account for his own survival. Many witnesses were also asked to describe the actions of Ismay: ‘Did you see Mr Ismay?’, ‘What was Mr Ismay doing?’ Those — mainly women — who were not invited to give evidence, related their tales of Ismay to the press.

Читать дальше