THE LOSS OF THE SS. TITANIC

Its Story and Its Lessons

by

Lawrence Beesley

B. A. ( Cantab .)

Scholar of Gonville and Caius College

One of the Survivors

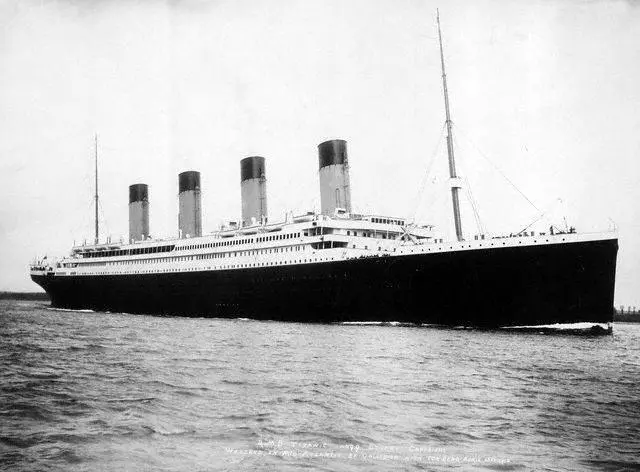

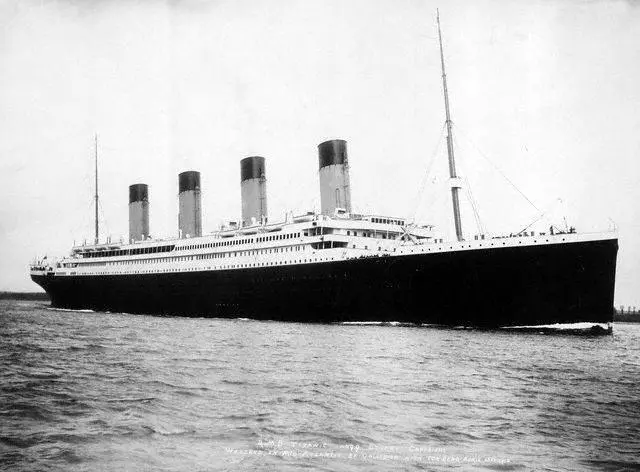

THE TITANIC

The circumstances in which this book came to be written are as follows. Some five weeks after the survivors from the Titanic landed in New York, I was the guest at luncheon of Hon. Samuel J. Elder and Hon. Charles T. Gallagher, both well-known lawyers in Boston. After luncheon I was asked to relate to those present the experiences of the survivors in leaving the Titanic and reaching the Carpathia.

When I had done so, Mr. Robert Lincoln O’Brien, the editor of the Boston Herald , urged me as a matter of public interest to write a correct history of the Titanic disaster, his reason being that he knew several publications were in preparation by people who had not been present at the disaster, but from newspaper accounts were piecing together a description of it. He said that these publications would probably be erroneous, full of highly coloured details, and generally calculated to disturb public thought on the matter. He was supported in his request by all present, and under this general pressure I accompanied him to Messrs. Houghton Mifflin Company, where we discussed the question of publication.

Messrs. Houghton Mifflin Company took at that time exactly the same view that I did, that it was probably not advisable to put on record the incidents connected with the Titanic’s sinking: it seemed better to forget details as rapidly as possible.

However, we decided to take a few days to think about it. At our next meeting we found ourselves in agreement again,—but this time on the common ground that it would probably be a wise thing to write a history of the Titanic disaster as correctly as possible. I was supported in this decision by the fact that a short account, which I wrote at intervals on board the Carpathia, in the hope that it would calm public opinion by stating the truth of what happened as nearly as I could recollect it, appeared in all the American, English, and Colonial papers and had exactly the effect it was intended to have. This encourages me to hope that the effect of this work will be the same.

Another matter aided me in coming to a decision,—the duty that we, as survivors of the disaster, owe to those who went down with the ship, to see that the reforms so urgently needed are not allowed to be forgotten.

Whoever reads the account of the cries that came to us afloat on the sea from those sinking in the ice-cold water must remember that they were addressed to him just as much as to those who heard them, and that the duty, of seeing that reforms are carried out devolves on every one who knows that such cries were heard in utter helplessness the night the Titanic sank.

THE TITANIC From a photograph taken in Belfast Harbour. Copyrighted by Underwood and Underwood, New York.

VIEW OF FOUR DECKS OF THE OLYMPIC, SISTER SHIP OF THE TITANIC From a photograph published in the “Sphere,” May 4, 1918 TRANSVERSE (amidship)

SECTION THROUGH THE TITANIC After a drawing furnished by the White Star Line.

LONGITUDINAL SECTIONS AND DECK PLAN OF THE TITANIC After plans published in the “Shipbuilder.”

THE CARPATHIA From a photograph furnished by the Cunard Steamship Co.

CHAPTER I

Construction and Preparations for the First Voyage

The history of the R.M.S. Titanic, of the White Star Line, is one of the most tragically short it is possible to conceive. The world had waited expectantly for its launching and again for its sailing; had read accounts of its tremendous size and its unexampled completeness and luxury; had felt it a matter of the greatest satisfaction that such a comfortable, and above all such a safe boat had been designed and built—the “unsinkable lifeboat”;—and then in a moment to hear that it had gone to the bottom as if it had been the veriest tramp steamer of a few hundred tons; and with it fifteen hundred passengers, some of them known the world over! The improbability of such a thing ever happening was what staggered humanity.

If its history had to be written in a single paragraph it would be somewhat as follows:—

“The R.M.S. Titanic was built by Messrs. Harland & Wolff at their well-known ship-building works at Queen’s Island, Belfast, side by side with her sister ship the Olympic. The twin vessels marked such an increase in size that specially laid-out joiner and boiler shops were prepared to aid in their construction, and the space usually taken up by three building slips was given up to them. The keel of the Titanic was laid on March 31, 1909, and she was launched on May 31, 1911; she passed her trials before the Board of Trade officials on March 31, 1912, at Belfast, arrived at Southampton on April 4, and sailed the following Wednesday, April 10, with 2208 passengers and crew, on her maiden voyage to New York. She called at Cherbourg the same day, Queenstown Thursday, and left for New York in the afternoon, expecting to arrive the following Wednesday morning. But the voyage was never completed. She collided with an iceberg on Sunday at 11.45 P.M. in Lat. 41° 46΄ N. and Long. 50° 14΄ W., and sank two hours and a half later; 815 of her passengers and 688 of her crew were drowned and 705 rescued by the Carpathia.”

Such is the record of the Titanic, the largest ship the world had ever seen—she was three inches longer than the Olympic and one thousand tons more in gross tonnage—and her end was the greatest maritime disaster known. The whole civilized world was stirred to its depths when the full extent of loss of life was learned, and it has not yet recovered from the shock. And that is without doubt a good thing. It should not recover from it until the possibility of such a disaster occurring again has been utterly removed from human society, whether by separate legislation in different countries or by international agreement. No living person should seek to dwell in thought for one moment on such a disaster except in the endeavour to glean from it knowledge that will be of profit to the whole world in the future. When such knowledge is practically applied in the construction, equipment, and navigation of passenger steamers—and not until then—will be the time to cease to think of the Titanic disaster and of the hundreds of men and women so needlessly sacrificed.

A few words on the ship’s construction and equipment will be necessary in order to make clear many points that arise in the course of this book. A few figures have been added which it is hoped will help the reader to follow events more closely than he otherwise could.

The considerations that inspired the builders to design the Titanic on the lines on which she was constructed were those of speed, weight of displacement, passenger and cargo accommodation. High speed is very expensive, because the initial cost of the necessary powerful machinery is enormous, the running expenses entailed very heavy, and passenger and cargo accommodation have to be fined down to make the resistance through the water as little as possible and to keep the weight down. An increase in size brings a builder at once into conflict with the question of dock and harbour accommodation at the ports she will touch: if her total displacement is very great while the lines are kept slender for speed, the draught limit may be exceeded. The Titanic, therefore, was built on broader lines than the ocean racers, increasing the total displacement; but because of the broader build, she was able to keep within the draught limit at each port she visited. At the same time she was able to accommodate more passengers and cargo, and thereby increase largely her earning capacity. A comparison between the Mauretania and the Titanic illustrates the difference in these respects:—

Читать дальше