Lord Mersey approached Ismay’s situation as though he had been making silent inquiries into his own case. Exonerating Ismay, he exonerated himself; ‘Nobody’, as Captain Marlow said, ‘is good enough.’

As he and Florence dined on the evening of 5 June, at 15 Hill Street, Ismay’s ordeal in the Drill Hall now over, a mile down the road in the Albert Hall a ‘One Hundred Years Ago’ ball was taking place. It was billed as the party of the season; the great dome was transformed into Brighton’s Royal Pavilion during the time of the Regent, and 4,000 people dressed in the fashions of 1812 came to celebrate Wellington’s victory at Waterloo. ‘The spirit of Beau Brummel was abroad,’ the papers reported, ‘and it was reflected in the magnificent costumes and dresses which were worn… the scene after midnight was brilliant in the extreme. It was easily the most fashionable and the most brilliant society function of the season. The floor was a fluttering, jingling, dazzling maelstrom.’ The ball was a nostalgic reminder of simpler, slower, happier days, but it also echoed the maelstrom of the last moments of the Titanic, where the combination of music, dressing gowns and dinner suits made the scene something like, as one passenger said, ‘a fancy dress ball in Dante’s Hell’. ‘Would life have been then more pleasant’, the Daily Mirror wondered the morning after the London party, ‘than it is today as we know it? Some enterprising spirit might next year organise a Futurist Ball which shall transport us to 2012… In 2012 we shall dread that war in the air is coming. If you are unhappy today, 1812 would have suited you no better, and no better than 2012 which, on notepaper, will look like a telephone number misplaced.’

They said I got away in a boat And humbled me at the inquiry. I tell you

I sank as far that night as any Hero. As I sat shivering on the dark water

I turned to ice to hear my costly Life go thundering down in a pandemonium of

Prams, pianos, sideboards, winches, Boilers bursting and shredded ragtime. Now I hide

In a lonely house behind the sea Where the tide leaves broken toys and hat-boxes

Silently at my door. The showers of April, flowers of May mean nothing to me, nor the

Late light of June, when my gardener Describes to strangers how the old man stays in bed

On seaward mornings after nights of Wind, takes his cocaine and will see no-one. Then it is

I drown again with all those dim Lost faces I never understood. My poor soul

Screams out in the starlight, heart Breaks loose and rolls down like a stone.

Include me in your lamentations.

Derek Mahon, After the

Titanic 1

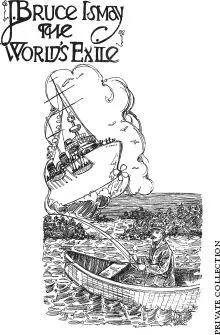

Cashla, meaning ‘twisting creek’ or inlet from the sea, is a Gaelic-speaking part of Connemara in County Galway. Ismay called the place by its anglicised name of Costelloe, and it was here that in 1913 he began what Walter Lord describes in A Night to Remember the life of ‘a virtual recluse’. Ismay’s fall, which was reported in newspapers across America, had become the stuff of legend. A feature in Oklahoma’s Times Democrat in 1914 described him as living ‘among the missing’ in the ‘bleakest’ place on earth. ‘Look where he hides in misery and shame. Day after day he must hear them, the shrieks of drowning men crying down the wind.’ In 1915, Utah’s Ogden Standard called Ismay ‘The World’s Exile’: ‘In one of the wildest spots on the west coast of Ireland where the silence is so heavy that one hardly dares to speak, lives in exile a man who until a few years ago had a high social standing in New York, had wealth and enjoyed all the pleasures and sports that his rank and financial standing afforded.’ Now, it was reported, local children chanted ‘coward coward coward’ when they passed his gate.

Costelloe Lodge, as Ismay’s house was called, lay in an oozing, seeping, percolating moonscape of bogs, loughs and boulders, gazed down upon by the pale blue form of the Twelve Pins Mountains. ‘It is awfully wild and away from everybody,’ he told Mrs Thayer after his first visit; ‘I will enjoy the place.’ The treeless limestone terrain, scooped out, scraped smooth, grooved and rent by ice-age glaciers, was inhabited by goats rather than people. The River Cashla, carving its course through the moor, cut through the ten acres of Ismay’s garden, enclosing the house on two sides. In nearby Clifden, the masts at the Marconi station picked up and passed on the stories that blew in from the sea. Like the house in Liverpool in which he had grown up, the windows of the Lodge looked out to the Atlantic.

To live in isolation is an appropriate penance for someone who has committed a breach of faith with the community of mankind. The symbolism of Ismay’s fate seems perfect: a seaman in exile from the sea, he hides on a primitive island which is also the womb of his ship, the flame of his honour keeping its vigil inside him like the last candle burning in a desecrated church. This is his Promethean punishment: Ismay the Titan bound forever to a rock, peregrines and ravens circling his head, the screams of the dead in his ears, frozen words hanging on the air, the empty sky and the empty ocean shimmering together as far as the vanishing horizon.

But that is not the story of the second half of Ismay’s life. The reality was harder than the public imagined it to be: Ismay simply carried on living, keeping out of the way and out of his own way. He did not retire to Costelloe Lodge and hide behind the sea; he visited Ireland for long summer breaks because the Cashla had the best trout- and salmon-fishing in all of Ireland. It was rumoured that every fish he caught on his hook reminded him of the drowned from the Titanic, but the truth is that Ismay found in fishing some of the forgetfulness he sought. The angler, says Isaac Walton, is ‘free from the unsupportable burthen of an accusing, tormenting Conscience: a misery that no-one can bear…’ Ismay was respected by the locals, to whom he gave employment and by whom he was called ‘Your Honour’, and his children, grandchildren and close friends would join him in Costelloe for memorable holidays. After her husband’s death, Florence continued to come here with the family. ‘For the first time,’ wrote Ismay’s granddaughter, Pauline Matarasso of her childhood visits to Connemara, ‘in this place of wilderness and wet I found a reality that was better than books. House and garden, large but not grand, stood close by an inlet where the peat boats came from the Aran Isles with their red-brown sails tied up to unload the turf that was the islanders’ only income.’ Ismay, who had always been private, now became more private; as Pauline Matarasso puts it, he reverted to type. ‘When he laid aside his public persona in 1913 he stood stripped to basics — a man so emotionally inhibited and so narrow in his interests as to be inapt for normal family and social life. Reclusion is the choice of those for whom the chronic pain of isolation seems preferable to the agony of rebuff. In this sense, he had long been a recluse.’ 2The catastrophe had confirmed for him that the true danger was neither icebergs nor instincts; it was other people.

As arranged, on 30 June 1913, Ismay handed over the presidency of the IMM and the chairmanship of the White Star Line to Harold Sanderson. When the Great War began, the White Star liners were turned into armed cruisers and the Ismay family left Sandheys in Liverpool to live in the London house at Hill Street. White Star had a good war: the Olympic — ‘Old Reliable’ as she became known — survived after ramming and sinking a submarine, and when America joined the Allies, the Baltic was proud to bring over the first US troops. After the Titanic, Ismay had set up a pension fund for maritime widows to which he donated £10,000. In 1919, he put forward a further £25,000 to begin a National Mercantile Marine Fund in appreciation of the ‘splendid and gallant’ bravery of the men in the British Mercantile Marine, with preference for grants and pensions to be given to those who had served on Liverpool-built ships. Ismay gave generously to charities for the rest of his life.

Читать дальше