As William Alden Smith left the last session of the New York hearings on the afternoon of Saturday 20 April, he told journalists on the steps of the Waldorf-Astoria that ‘the surface has barely been scratched. The real investigation is yet to come.’

Ismay and his bodyguards arrived in Washington on Sunday at 8 p.m., exactly one week after the Titanic hit the iceberg. Hundreds of people were gathered around the entrance to Willard’s Hotel in the hope of getting a look at the infamous coward, and so Ismay slipped in through the back door and was whisked up the stairs to the suite which had been reserved for his party. Lightoller was booked into the less grand Continental together with the Titanic ’s frustrated crew, who, he said in his memoirs, ‘refused point blank to have anything more to do with either the inquiry or the people, whose only achievement was to make [them] look ridiculous’. With the help of Bryce and Franklin, Lightoller managed to ‘bring peace to the camp’, but he was annoyed at being quartered with his inferiors rather than with the White Star officials he was doing so much to protect, and insisted on being either moved to the Willard or provided with a separate floor and dining arrangements. The Continental’s staff muttered about how the rich and the poor on the Titanic were now bedding down side by side on the ocean floor.

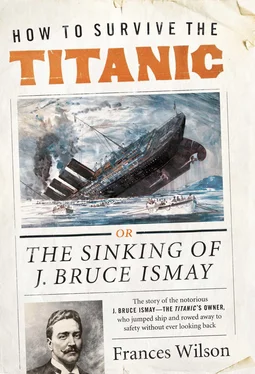

The papers that weekend had run Emily Ryerson’s sensational account of her encounter with Ismay when she had been walking with Mrs Thayer on the deck of the Titanic. ‘Sunday morning Mr Ismay showed to a woman passenger a wireless message with an ice warning. She asked if the Titanic would not go slower and Mr Ismay replied laughing, “No FASTER! We want to get by it”.’ Here was the evidence the inquiry needed to prove that Ismay was party to negligence; it also implied that he had lied when he told Senator Smith that he was not aware on that day of any proximity to ice. Mrs Ryerson agreed to swear to her story, and that night Ismay issued a press release. Unlike the few words he gave to reporters when he left the Carpathia, it seems likely that Ismay himself drafted this next statement which appeared in The Times on 23 April, and that it is therefore his only published self-defence. It was ‘impossible’, Ismay said, ‘to answer every false statement, rumour or invention that has appeared in the newspapers… but I do not think that courtesy requires me to be silent in the face of the untrue statements’. He stressed his initial willingness to appear at the inquiry, ‘without subpoena’, and to answer every question put to him ‘to the best of my ability, with complete frankness and without reserve’. He described again, this time for the benefit of the British public, his actions on the Titanic, repeating that he had been ‘a passenger and [therefore] exercised no greater right or privileges than any other passenger. I was not consulted by the commander about the ship, her course, speed, navigation, or her conduct at sea.’ He stated that he had not, as claimed in the press, been at a dinner party with the Captain on Sunday night, and that it was ‘absolutely and unqualifiably false that I ever said that I wished that the Titanic should make a speed record or should increase her daily runs’. He confirmed that an ice warning from the Baltic had indeed been ‘handed to me by Captain Smith, without any remarks, as he was passing me on the afternoon of Sunday, April 14. I read the telegram casually and put it in my pocket,’ and insisted that he had said nothing to Mrs Ryerson about the ship being speeded up. Had the warning ‘aroused any apprehension in my mind — which it did not — I should not have ventured to make any suggestion to a commander of Captain Smith’s experience and responsibility, for the navigation of the ship rested solely with him’. Ismay described, yet again, how he had been asleep at the time of the collision, how he worked at loading the starboard boats, and how, as the forward collapsible lifeboat was being lowered, ‘Mr Carter, a passenger, and myself got in.’ He explained that the Yamsi messages sent from the Carpathia ‘have been completely misunderstood’ and that he could not be accused of trying to avoid the Senate Committee’s inquiry because he had ‘not the slightest idea that any inquiry was contemplated’. He concluded by saying that ‘it was the hope of my associates and myself that we had built a vessel which could not be destroyed by the perils of the sea or the dangers of navigation. The event has proved the futility of that hope.’

Futility had been the title of a little-read novella by Morgan Robertson, published fourteen years before. It told the story of a 45,000-ton ‘floating city’ called the Titan, the largest ship ever built, which left New York in April with 3,000 passengers. Speeding along at 25 knots she met an iceberg in the place where the Titanic would later meet her fate, and because the Titan was believed to be ‘unsinkable’, and carried ‘as few boats as would satisfy the laws’, she went down with most of her passengers still on board. 12

The following day the inquiry reconvened in the sumptuous new Caucus Room of the Senate Office Building, where the McCarthy and Watergate hearings would in time be heard. ‘Washington this time of year’, reported the Daily Telegraph, ‘is crowded with honeymoon couples, and the weather is so mild that the windows of the Senate are open all day long. The scent of spring flowers wafted into the court, and the words of witnesses are punctuated by the sweet notes of birds singing in the leafy trees outside. Ladies in spring dresses sit in court fanning themselves, and at times so crowded is the courtroom that the atmosphere is insufferably close.’

First to the stand was Philip Franklin, the forty-one-year-old American vice-president of the IMM. The wreck of the Titanic, Franklin said, ‘has demonstrated an entirely new proposition that has to be dealt with — something that nobody had ever thought of before. These steamers were considered tremendous lifeboats in themselves.’ It was, Franklin now believed, ‘impossible to build a non-sinkable ship’. Smith asked Franklin to read aloud every Marconigram he had sent and received in relation to the Titanic, including, to Ismay’s cringing embarrassment, the Yamsi messages. Their contents were duly noted down by the newsmen and reported the next day in papers around the world. The reproduction of the Marconigrams gave the story a sense of synchronicity; readers felt as though they were experiencing the disaster and its aftermath in real time. It was vital, Franklin stressed at length, that Ismay’s messages not be misunderstood. It was not his own welfare he was concerned with when he wanted to return on the Cedric, but that of the crew. ‘Criticism has been seriously made to the effect that those messages were sent entirely with the idea of getting the crew away, and of Mr Ismay’s also getting away on account of what information might come out from the crew. I want to say that that was not in Mr Ismay’s mind. Everybody realises the importance of getting these members of the crew away from the country at the earliest possible moment.’ Franklin spoke about the danger of letting a ship’s crew loose in a city, after which Smith released him. Next to the stand was Joseph Boxhall, the Titanic ’s Fourth Officer, who recalled how, contrary to Lightoller’s testimony, only two boats had been lowered during the boat drill in Southampton.

The New York Times that day carried an interview with Inman Sealby, formally a captain of the White Star Line and now a student of admiralty law at the University of Michigan. Sealby had been dismissed by the company in 1909 when the Republic sank under his command. In the twenty-five years he had worked for the Ismay family, Sealby said, ‘I never saw anything which would have led me for one minute to anticipate anything but the best of conduct in Mr Ismay at all times and under all circumstances. Until the exact circumstances of his escape from the Titanic are placed before me it would be impossible for me to pass an opinion in the matter.’

Читать дальше