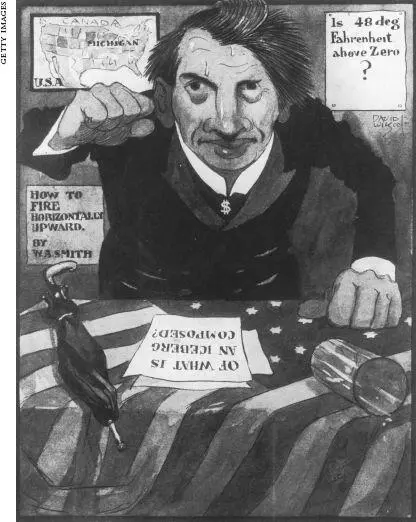

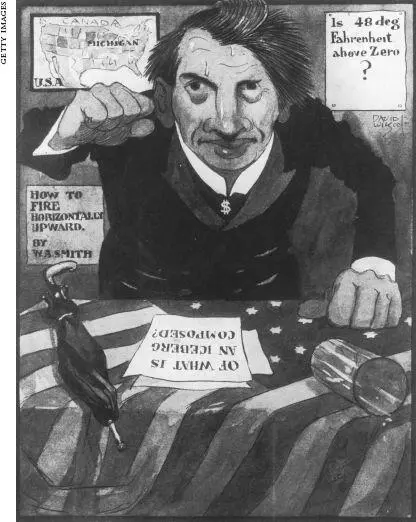

The English press saw Smith as no more than a snapping terrier whose self-importance and evident ignorance could be mercilessly lampooned. ‘The Michigan senator’, wrote the London Standard, ‘is less qualified as an investigator than the average individual to be picked up in the average American streetcar.’ Smith was sent up as a figure in music-hall burlesque; for Joseph Conrad, who wrote about the wreck for an English literary journal, he was Mr Bumble, the cocked-hatted power-hungry beadle in Oliver Twist, and Conrad referred to the inquiry as ‘Bumble-like proceedings’. Smith’s only British defendant was Alfred Stead, whose father, the journalist W. T. Stead, had gone down with the ship. ‘The newspapers,’ Alfred Stead wrote, ‘tell us that Senator Smith… is a “backwoodsman”, ignorant of all nautical affairs. I do not care if he is a Red Indian. His ignorance, if it exists, is excusable ignorance, whereas the ignorance of officers and seamen in their duties is criminal negligence.’

A cartoon of Senator Smith, published in the Graphic, 1912

But it was not the difference between Ismay and Smith, Ismay and Rostron, or England and America which lent the inquiry its peculiar quality; it was the sameness of Ismay and Second Officer Lightoller. Generally regarded as one of the heroes of the night, Lightoller had loaded the lifeboats on the port side and then, as the ship was descending, had taken ‘a dive’ and found himself drawn, by a sudden rush of water, to the wire mesh of a giant air shaft on which he became glued by the pressure of the sea. Unable to detach himself, Lightoller assumed that this is how he would die when a blast of hot air came up the shaft and blew him back to the surface of the water. He was then pulled under again, and just as he was ‘rather losing interest in things’, as he later put it, he eventually surfaced by the side of an overturned collapsible boat. Holding onto a piece of rope, he floated alongside it until one of the ship’s giant funnels fell, missing him by inches and causing the raft, and Lightoller, to be flung fifty yards clear of the sinking Titanic. Men were now starting to scramble onto the lifeboat and Lightoller joined them, eventually taking control. ‘If ever human endurance was taxed to the limit,’ he said in his memoirs, ‘surely it was during those long hours of exposure in a temperature below freezing, standing motionless in our wet clothes.’ He ordered every man on the upturned boat to face the same way and to ‘lean to the left or stand upright or lean to the right, as the case might be. In this way we managed to maintain our foothold on the slippery planks by now well under water.’ Here the party remained for several hours until they were taken on board two of the half-empty lifeboats.

Senator Smith was unmoved by accounts of Lightoller’s survival; as far as he was concerned Rostron was the saint of the story and Lightoller simply a stooge of Ismay, more concerned with keeping his job with the White Star Line than preventing future tragedies at sea. Had they not been whispering together in the cabin of the Carpathia, cooking up their plot to abscond on the next available White Star liner without so much as setting foot on American soil?

Lightoller was called to the stand after lunch. Described by the papers as ‘strong and powerfully built’ with a ‘virile sea-worn face’, he told the inquiry in a clear, deep voice how he had retired to bed and was dropping off to sleep when he heard ‘a slight shock and a grinding sound. That was all there was to it. There was no listing, no plunging, diving, or anything else.’ He then left his room in his pyjamas and went to the bridge where he found the Captain and First Officer Murdoch motionless, looking ahead. The ship was still moving and so he assumed all was well. Lightoller then returned to his room. ‘What for?’ asked Smith.

‘There was no call for me to be on deck,’ replied Lightoller.

‘No call, or no cause?’ corrected Smith.

‘As far as I could see,’ said Lightoller, ‘neither call nor cause… I did not think it was a serious accident.’ As he walked back, Lightoller saw no one except the Third Officer, ‘who left his berth shortly after I did’. The two men briefly conferred about the incident and concluded that ‘nothing much’ had happened.

‘Did you go back to your room under the impression that the boat had not been injured?’ asked Smith.

‘Yes, sir,’ said Lightoller.

‘Didn’t you’, wondered Smith, ‘tell Mr Ismay that?’

Lightoller answered that he had not yet seen Ismay; that he would only see Ismay once, about twenty minutes later, and that he ‘really could not say’ whether he had or had not then told him there was no cause for concern. Lightoller went back to bed for ‘ten minutes’. When he was roused by Fourth Officer Boxhall he put some clothes on top of his pyjamas and went out on deck. Ismay, when Lightoller saw him, was standing stock-still and alone. According to Lightoller the entire evening had been conducted in silence; he appears in his account like a man in a dream, sleepwalking to the bridge and then back to bed where he wakes with a start, realising that everyone is going to die.

Nor did Lightoller recall seeing any passengers on the deck when the ship was going down. ‘I ask you again,’ Smith persisted: ‘There must have been a great number of passengers and crew still on the boat, the part of the boat that was not submerged, probably on the high point, so far as possible. Were they huddled together?’

‘They did not seem to be,’ said Lightoller. ‘I could not say, sir; I did not notice; there were a great many of them, I know, but as to what condition they were in, huddled or not, I do not know.’ However, in his memoirs, written twenty-three years later, Lightoller remembered the crowds and what condition they were in. They were washed back in a ‘dreadful huddled mass… It came home to me very clearly how fatal it would be to get amongst those hundreds and hundreds of people who would shortly be struggling for their lives in that deadly cold water.’

Lightoller explained how the Captain gave him no order to load the lifeboats on the port side, how he had placed twenty-five people into the first boat because he was unconfident about filling it with more, how he had personally tested all the lifeboats when the ship was in Southampton (in his memoirs, he admitted to testing only ‘some of them’), and how it was only as she began to list that he realised there was a genuine emergency. There had been no confusion amongst the passengers, who ‘could not have stood quieter had they been in church’, and no restraint on the movement of those in steerage. No other man had tried to join them on the upturned lifeboat because everyone else was ‘some distance away’.

As for the question of whether he had seen any ice warnings, Lightoller did not know they were in ‘the vicinity of icebergs’, he ‘could not say’ whether he saw the ‘individual message’ sent by the Amerika on Sunday evening or heard of it even though it was received during his shift. (This particular Marconigram, which never reached the bridge of the Titanic from the communications room, had been intercepted and sent to Washington where it ended up on Senator’s Smith’s desk.) Would it not, asked Smith, ‘have been the duty of the person receiving this message to communicate it to you, for you were in charge of the ship?’ Lightoller replied only ‘under the commander’s orders, sir’ and that while he did not know about that particular message he ‘knew that a communication had come from some ship; I can not say that it was the Amerika … speaking of the icebergs and naming their longitude… the message contained information that there was ice from 49 to 51’.

Читать дальше