You enter the reception room which is Jacobean, the restaurant is in the Louis Seize period with beautiful tapestry on the walls, the lounge is Louis Quinze with details copied from Versailles. The reading and writing rooms are of 1770, but in pure white, with an immense bow window. The smoking room is Georgian of the earlier period… The various apartments are decorated in almost as many styles and combinations of styles as there are rooms to be adorned… You may sleep in a bed depicting one ruler’s fancy, breakfast under another dynasty altogether, lunch under a different flag and furniture scheme, play cards or smoke, or indulge in music under three other monarchs, have your afternoon cup of tea in a verandah which is essentially modern and cosmopolitan, and return to one of the historical periods experienced earlier in the day for your dinner… If a good democratic citizen of the US thinks he can enjoy his voyage better in an Empire suit of rooms — in a more comfortable bed than the emperor ever had — or a French republican likes a royal suit of one of the Louis monarchs; or an ardent German socialist suddenly evinces a desire to travel in luxury in an Imperial suit… whatever the taste, the steamship company will welcome and make them comfortable, as long as they pay the fare in advance. 51

During his tours of the ship, Ismay noticed that the crew’s galley was without a potato peeler, that cigarette holders were needed in the lavatories, and that the reception room, as the most popular room in the ship, would benefit from a further fifty cane chairs and ten more tables. The mattresses on the beds were too ‘springy’ — ‘the trouble with the beds is entirely due to their being too comfortable’ — and as the companionway between the lounge and the smoking room on A Deck was not used, the space might be better converted into a few extra staterooms. A further suggestion of Ismay’s was to limit the service from the pantry to the saloon to one door on each side; closing off the other doors ‘will enable us to put two additional tables in the Saloon, giving an increased sitting capacity of eight people’. He recorded that the voyage out took ‘five days, 16 hours, 42 minutes, average speed 21.7… daily runs, 428 miles, 534, 525, 548’, and before returning to Southampton he arranged for the Olympic to be fully coaled in New York. 52

He was clearly not a regular passenger. But nor did Ismay have the swagger and authority of a cigar-chewing shipowner. He spent his time on board the Olympic rearranging the deckchairs.

That same year, Country Life ran an illustrated feature on Dawpool which described the pile as ‘a fine and acknowledged masterpiece, familiar and honoured wherever English architecture is held in esteem’. The pictures, however, seemed to be of an empty house. Instead of photographing the rooms in which the family lived, the magazine gave its readers a look at one of the vast chimneypieces and a glimpse up a panelled staircase. The author of the accompanying article suggested that the lack of any signs of life allowed ‘the architectural qualities of the building to stand out in strong relief unconfused by the competing charms of the beautiful furniture and pictures’, but there was no disguising the fact that Dawpool was uninhabited. Following Margaret Ismay’s death in 1907, the house had become a shell. It ‘had more than answered its purpose’, Margaret Ismay told Shaw; ‘for it had interested and amused Mr Ismay every day of his life for fifteen years’. One after another their sons refused to live there. The house, which Shaw thought might be converted into a sanatorium or a smallpox hospital, lay empty until it was sold in 1927. Then the new owner had it demolished which, due to its tremendous sturdiness, took great quantities of dynamite. Dawpool was inhabited for only thirteen of its forty years, a lifespan slightly longer than that of the ships it resembled. Nothing in the Ismays’ Brobdingnagian world lasted for long.

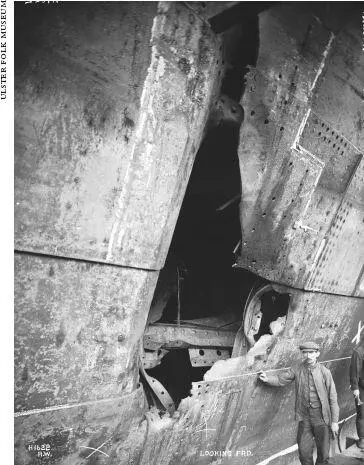

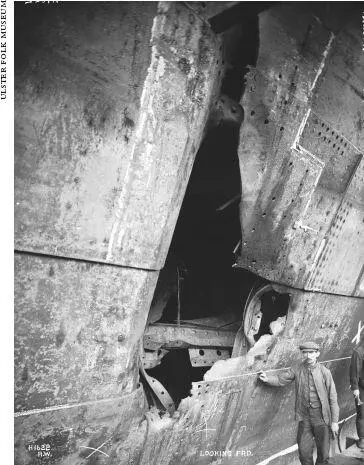

The maiden voyage of the Titanic was to have been 20 March, but because of a recent accident involving the Olympic the date was put forward to 10 April, which had originally been scheduled as the date of her second voyage. On 20 September 1911, as she was beginning her fifth Atlantic crossing under the command of Captain Smith, the Olympic had collided with the HMS Hawke, less than half her size. A large triangular hole, eight feet by fifteen feet, was punctured in Olympic ’s side.

The hole in the side of the Olympic

Her watertight doors were ordered closed, and while two compartments were flooded the others remained dry and she stayed afloat. The passengers, who had been at lunch when their cabins were destroyed, were now offloaded and their passage cancelled. The Olympic was towed to Southampton where it took ten days to patch up her hull. She was then taken back to Harland & Wolff for the repairs proper to begin; because her propeller shaft, bent in the collision, needed replacing it was thought best to use the one due to be fitted to the Titanic. The collision cost White Star Line £130,000 in repairs and £154,000 in lost revenue when the next three voyages had to be cancelled. The Olympic ’s crew, who were without work for a month, were given no compensation for loss of income. The subsequent inquiry concluded that Captain Smith was guilty of recklessness. The Captain was shaken — this was his first serious accident in thirty years’ service — but the Olympic stayed afloat. These new White Star liners, Smith now believed, were indestructible.

On 21 March, Ismay’s eldest daughter, Margaret, married Captain Ronald Cheape in what the papers called the ‘first society wedding of the year’. It cannot have been an easy time for Ismay who, like many unhappily married men, focused his love on his favourite daughter rather than his wife. Like Ismay, Ronald Cheape was tall and handsome with a love of guns and discipline; he was also a Scot and the newlyweds were due to move to Mull after a period in India. The marriage ceremony took place at St George’s, Hanover Square, and the reception was held at the Ismays’ new London home at 15 Hill Street, Mayfair. Margaret, who was initially to have joined her father on the Titanic, was on her continental honeymoon when the Ismay family drove down to the Southampton docks in their Daimler Landaulette on 9 April. [1] In June 1907, the “White Star Line had moved their terminal from Liverpool to Southampton to make it easier for the smart passengers from London to reach”.

The depleted clan stayed the night in the South Western Hotel, and, after waving Bruce off, Florence and the children went on a motoring trip to Wales. Lord Pirrie could not join Ismay on the Titanic because he was recovering from an operation for an enlarged prostate gland; James Ismay, too, was ill (with pneumonia), and J. P. Morgan was forced to cancel at the last minute due, he said, to the pressure of work. 53It seems that Ismay, who now took over Morgan’s stateroom, was also looking for a get-out clause: two weeks before the departure date he wrote to Philip Franklin, vice-president of the IMM, suggesting that he call off his voyage, ‘in view of the threatened investigation of the Shipping Companies’. Franklin replied: ‘Confident no reason to alter your plans.’ 54As she left her berth in Southampton harbour, the suction from the Titanic snapped the mooring lines of the neighbouring ship, the New York. Action from Captain Smith, the pilot and a tug managed to prevent the inevitable collision.

Читать дальше