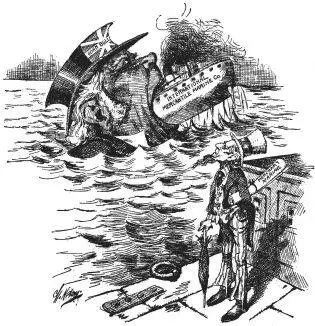

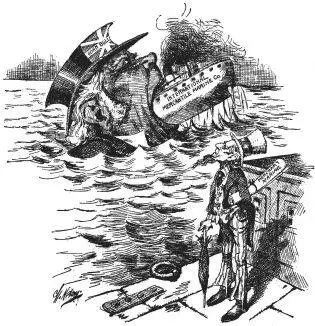

A cartoon in the New York Globe pictured John Bull, his head emerging from the Atlantic, devouring the IMM in the form of a ship. ‘He’s swallowed it!’ says America, but the truth is that when Ismay jumped, it was J. Pierpont Morgan who swallowed him whole.

‘He’s Swallowed It Be Gosh!’

His appointment, noted the Glasgow Evening Times, ‘was consonant with the whole of the Ismay family history. An Ismay never goes back.’ And Ismay did not return to live in New York, a slight that the city would find hard to forgive. Instead, as he patiently explained to journalists wondering where he would now be residing, the headquarters of the IMM would be sometimes in America, sometimes in England, sometimes on the high seas and sometimes on a golf course in Scotland. They would be, Ismay famously said, ‘wherever I am’.

In an attempt to envisage the new president’s working life, the satirical journal The Syren ran, in October 1905, an imaginary interview with J. Bruce Ismay. He is pictured in a ‘simple apartment, about 150ft in length and 80ft in breadth, fitted and furnished plainly, indeed austerely’. The walls are panelled in the ‘rarest mahogany, inlaid with mother of pearl’, the light fittings are ‘solid silver’, and ‘the furniture is priceless. Over one of the massive mantelpieces hangs a large oil painting by a well-known Scotch academician, entitled “Bruce Vanquishing his Enemies”.’ Behind what looks like a ‘large pianola’, but turns out to be ‘a wonderful entanglement of telephone and telegraph wires, speaking tubes, etc.’, Ismay can be found keeping ‘in constant and close touch with each sub-section of each section of each division of each department of each branch of each Line of each Trust of the great TRUST itself’.

The story goes that one summer evening later in the year, Bruce and Florence Ismay went to dinner at Downshire House in Berkeley Square, the home of William, now Lord, Pirrie who had been managing director of Harland & Wolff since the death of Sir Edward Harland in 1894. An Irishman determined to make his mark on London society, Pirrie was a famously lavish host. During the evening, the shipowner and the shipbuilder agreed, over coffee and cigars, to build the twins Olympic and Titanic, each 15,000 tons bigger than the Lusitania and the Mauretania.

It’s an evocative image: an opulent candlelit dinner enjoyed by two successful businessmen and their glittering wives in the Mayfair of the gilded age. Ismay and Florence are chauffeured down to Berkeley Square from their own magnificent house in Chesham Street, Belgravia; after dessert the women drift off to gossip and play cards in the fern-filled drawing room while the men, slightly drunk, decide to build the most enormous and fabulously equipped ships the world has ever known. The evening at Downshire House is the perfect accompaniment to the evening at Gustavus Schwabe’s mansion forty years earlier.

Many evenings were shared between the Pirries and the Ismays when they were all in London, but it is unlikely that the idea for the Titanic was born during a neighbourly supper. Nor is it necessary to bathe the birth of the ship in such a sepia glow; there was nothing particularly inspired or outlandish in the idea of building a bigger ship than the one before. Technology was moving at such a rate that every ship the White Star Line commissioned from Harland & Wolff was bigger than the last; it went without saying that their next group of ships would need to be considerably larger and more dramatic if they were to grab the headlines from the two Cunarders. Nor is it likely that the idea for the Titanic was conceived so late in the day. The Lusitania and the Mauretania were to be launched in late 1907: why would the power-hungry J. P. Morgan, whose ambition was to eliminate competition on the North Atlantic, wait until a few months before the launch of the already famous Cunarders before reacting to their challenge?

The part played by William Pirrie in the story of the Titanic is, like the similarly named William Imrie, that of the forgotten partner. Except that Pirrie was more than a partner; he was the world’s leading shipbuilder and regarded Harland & Wolff as his ‘personal fiefdom’. 46It was Pirrie who was behind the deal with J. P. Morgan, Pirrie who persuaded Ismay to join the conglomerate, Pirrie who pushed for Ismay as the president of the IMM, Pirrie who probably dreamed up the Titanic. The appearance on the scene of J. P. Morgan made Pirrie nervous about his own future: under Bruce Ismay’s leadership the White Star Line could go under and Harland & Wolff would then lose their best customer. But should White Star join up with Morgan, a good deal more work might come Pirrie’s way: Harland & Wolff might build ships for the entire conglomerate. So rather than standing against the threat of a syndication, after secret discussions with Morgan Pirrie decided to promote the IMM as ‘something magnificent and ingenious’ and he pressurised Ismay, who had initially called the whole thing ‘a swindle and a humbug’, into following suit. 47The White Star Line would sooner contemplate establishing a line to the moon, Ismay had originally told reporters, than be bought by J. P. Morgan. He now quickly changed his tune. Under the terms of the arrangement between White Star and the IMM, ‘all orders for new vessels and for heavy repairs, requiring to be done at a shipyard of the United Kingdom, were to be given to Harland & Wolff’. 48‘I do not mind confessing,’ Pirrie wrote to Ismay when he at last accepted the IMM presidency, ‘that it was with something very like a sigh of relief that I heard that all had been satisfactorily settled,’ 49and the IMM was generally known as ‘the Pirrie Relief-Bill’.

In Titanic, written in two weeks and published one month after the shipwreck, the popular journalist Filson Young gave his memorable description of her construction at Harland & Wolff.

For months and months in that monstrous iron enclosure there was nothing that had the faintest likeness to a ship; only something that might have been the iron scaffolding for the naves of half-a-dozen cathedrals laid end to end. Far away, furnaces were smelting thousands and thousands of tons of raw material that finally came to this place in the form of great girders and vast lumps of metal, huge framings, hundreds of miles of stays and rods and straps of steel, thousands of plates, not one of which twenty men could lift unaided; millions of rivets and bolts — all the heaviest and most sinkable things in the world. And still nothing in the shape of a ship that could float upon the sea… The scaffolding grew higher; and as it grew the iron branches multiplied and grew with it, higher and higher towards the sky, until it seemed as if man were rearing a temple which would express all he knew of grandeur and sublimity… 50

Like other writers on the Titanic, Young describes the ship as sinister while the excesses of her twin — whose simultaneous construction he does not mention — tend to be depicted with the humour, respect and affection befitting an eccentric but dependable aunt.

On 31 May 1911, Morgan and Ismay were present at Harland & Wolff for the launch of the still unfurnished Titanic and the handing over of the now completed Olympic. On 14 June, the Olympic set off on her maiden voyage to New York with Ismay and Florence on board. While Florence enjoyed society, Ismay kept an eye on the professionalism of the crew and made a note of the areas in which the ship was deficient, details of which he sent in Marconigrams to the White Star office in Liverpool. Her accommodation extended over five decks; she had electric elevators, a barber’s shop and a dark room for photographers. She was thoroughly modern, but she was also, as a contemporary remarked, a time machine:

Читать дальше